The Architecture of the Brain

© 2020 Sarah Roehrich, M.S, CCC-SLP

Four years ago, the 7th graders at the Galvin Middle School in Wakefield, MA, heard a lecture called Your Plastic Brain, by Dr. Takao K. Hensch, and played a game about brain plasticity called The Brain Architecture Game. (1, 11) With Brain Basics graduate students associated with Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, and guidance from Dr. Judy L. Cameron, the 7th graders worked in small groups to build the tallest, sturdiest brains they could, depending on the types of building materials they received. (1)

According to Dr. Hensch, a professor of molecular and cellular biology at the Center for Brain Science at Harvard University, brain plasticity, or neuroplasticity, is defined as changes that take place in the brain throughout one’s lifetime. (10) Dr. Hensch serves as the director of the NIMH Silvio Conte Center for Mental Health Research at Harvard University. In his video, Your Plastic Brain, Dr. Hensch describes two types of brain plasticity. Functional brain plasticity refers to the strengthening or weakening of brain architecture in response to the frequency of experiences. (11) For example, repeated, positive, face-to-face, social interactions between babies and caretakers, can help babies develop sound maps that provide foundations for learning native languages and reading later on. (15) Alternatively, babies that receive very few face-to-face, social interactions, will develop less intricate sound maps.

A second type of brain plasticity is known as structural plasticity. Structural plasticity refers to brain architecture that changes over time. Some circuits disappear in a natural process called pruning, and new circuits are created as a result of new experiences. (11) For example, brain development from birth-age 5 is characterized by extensive changes in brain architecture, which, in turn, creates a foundation for the development of new skills such as reaching, crawling, grabbing, walking, talking, and learning.

Based on his article, “The Power of the Infant Brain,” and his video, Your Plastic Brain, Dr. Hensch describes how brain plasticity develops in infants, allows people to learn new skills at any age, and creates new neural connections that compensate for injuries and/or disease. (10, 11)

Brain Plasticity in Infants

To help you understand how early brain plasticity works, it is helpful to imagine a baby just after birth. At birth, an infant leaves a mother’s womb and is flooded with sensory information from sights, sounds, smells, touch, and sensations that the infant experiences for the first time.

A baby can see faces or a red ball 10 inches away, but her vision is fuzzy, unclear, and underdeveloped. The infant can also hear voices and sounds, but may or may not be able to locate where the sounds are coming from. (10, 11, 16) The infant’s sense organs send new sensory information to the brain to be processed. But, the infant’s brain is immature, and only partially developed. It contains 100 billion neurons and an overgrowth of synapses. (5) It is extremely “plastic,” and does not have pre-established pathways to process incoming sensory information. (11)

Neurons are special brain cells that are directed by genes to send out projections and electrical signals to connect to each other. (6, 23) In the book, Scientist in the Crib, Alison Gopknik et. al. describe neurons as growing telephone wires that communicate with each other. (8)

Neurons create circuits that process different types of sensory information. For instance, one circuit might develop in response to visual information, and a different circuit might develop in response to auditory information. (10, 11)

According to scientists, circuits that “fire together, wire together.” (10) In other words, circuits that are reinforced through repeated experiences become stronger. They create a basic foundation for future brain architecture. Circuits that are not reinforced through experiences become weaker and fade away through a natural process called pruning. (10, 11)

Perspectives on Self-Care

Be careful with all self-help methods (including those presented in this Bulletin), which are no substitute for working with a licensed healthcare practitioner. People vary, and what works for someone else may not be a good fit for you. When you try something, start slowly and carefully, and stop immediately if it feels bad or makes things worse.

In his lab, Dr. Hensch is particularly interested in critical periods in brain development. Critical periods are extra intense time windows of development in which brain architecture develops in response to stimuli provided by life experiences. Neuroscientists have identified critical periods for vision, hearing, language, and various types of social interaction. For example, in normal development, an infant’s vision will mature in response to light from the environment, and a baby’s recognition of speech sounds in his native language will evolve in response to social interactions with his caretakers. (10, 18)

Dr. Hensch points out that critical periods are time sensitive. Though most critical periods occur in early childhood, some extend into the teen years. When critical periods end, neurons develop insulation covers. Insulation helps ensure that pathways transmit electrical signals across the brain, and provides reinforcement to established brain circuits. This, in turn, makes the brain less plastic, and more difficult to change as a child matures. (10, 11)

In general, critical periods for brain growth open and close on schedule. However, critical periods can be derailed by a host of unexpected circumstances such as medical problems, trauma, lack of stimulation, neglect, abuse, and toxic stress. (10, 11)

Building Connections: Shaping Foundations for Learning

Dr. Hensch states that the senses for sight, sound, touch, smell, and taste did not evolve separately from each other. (11) As the baby’s brain and body mature, different sensory circuits become intertwined, shaping new brain architecture. (6) In his lecture, Dr. Hensch used colorful, 3D images and videos created with an electron microscope to show how neurons originating in different parts of the brain build circuits across brain regions. These images and videos were created by students in Dr. Jeff Lichtman’s lab at Harvard University. (11)

Connections between sensory organs allow our senses to work together to help us perceive our world. The accurate perception of information often involves more than one sensory system, such as vision and sound. This concept is known as multi-modal perception. (11)

As babies grow, they rely more and more on multi-modal perception to explore their environments and interpret their experiences. (11) For example, in normal development, during the first 8 months of life, babies’ vision, listening, and motor skills improve and integrate to the point where babies can locate, move towards, grasp, and explore objects they spot at eye level on the other side of a room.

In terms of communication, a baby or toddler learns to recognize and imitate sounds, words, gestures, and signs, by listening to what caretakers say, watching what caretakers say and do, and exploring toys, foods, and items that adults label and talk about over and over again. Language is learned in the context of routines that involve talking, eating, playing, singing, storytelling, reading, and other experiences shared between a caretaker and a child. (18)

Babies are naturally curious; they watch every movement and listen to every sound they hear around them. When parents talk, babies look up and watch their mouth movements with intense wonder. (18) Parents respond in turn, speaking in “motherese,” a special variant of language designed to bathe babies in the sound patterns and speech sounds of their native language. (13) Motherese helps babies hear the “edges” of sound, the very thing that is difficult for babies who exhibit symptoms of dyslexia and auditory processing issues later on. (15, 18)

Dr. Patricia K. Kuhl, a distinguished speech-language pathologist, researcher, and co-director of the Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences at the University of Washington, explains that a baby’s interactions with others engages the social brain, a critical element for helping children learn to communicate in their native and non-native languages. (13, 18) In fact, in one of her cross-cultural research studies, which compared babies learning directly from teachers, and babies learning directly from screens, Dr. Kuhl showed that babies could not learn their first words by watching a show on a screen. Instead, she insists that babies must have face-to-face interactions to learn how to speak. (14, 18)

Over time, by listening to and engaging with the speakers around them, babies build sound maps which set the stage for them to be able to say words and learn to read later on. In fact, based on years of research, Dr. Kuhl has discovered that babies’ abilities to discriminate phonemes at 7 months-old is a predictor of future reading skills for that child at age 5. (15)

The Brain Architecture Game

The Brain Architecture Game is a tabletop game that teaches participants about the influential role experiences have on early brain development in the first 8 years of life. It is designed to help the public and policymakers understand the science of early brain development in a hands-on, meaningful way. (17) Two short videos from the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, “Experiences Build Brain Architecture” and “Serve and Return Interaction Shapes Brain Circuitry,” nicely depict how early brain development happens. (6)

The game is the product of a 10+ year collaboration between developmental scientists from the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, communication scientists at the FrameWorks Institute, and researchers from the Creative Media & Behavioral Health Center at the University of Southern California, and the Clinical & Translational Science Institute at the University of Pittsburgh. This unique collaboration has been hosted and supported by the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (17)

A number of people have made significant contributions to developing the game including Dr. Judy L. Cameron, the first adopter and playtester of the game, Marientina Gotsis, the co-inventor and Executive Producer of the game, and many others. (17, 21, 22) Dr. Cameron is a professor of psychiatry, who works at the Clinical Translational Science Institute at the University of Pittsburgh. She is also a member of the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Her research focuses on how everyday stressors affect long-term health. (21) She has played a significant role in testing and helping to develop the current version of the game. She has also traveled throughout the United States and Canada teaching thousands of adults and a number of high school students how to play the game at workshops and conferences. (17) Dr. Cameron is particularly interested in how high school students and adults interpret the game differently, depending on their ages and life experiences.

Marientina Gotsis is an associate professor of the Practice of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California. She is the director of the Creative Media & Behavioral Health Center, an organized research unit between the School of Cinematic Arts and the Keck School of Medicine, which was established in 2010. This center designs, develops and evaluates entertainment applications at the intersection of behavioral science, medicine and public health. (22) Marientina serves as a supervisor in Cinematic Arts, Media Arts, Games, and Health. As Executive Producer of The Brain Architecture Game, she has led several workshops using the game in the US and Europe in smaller groups. She has developed new versions of the game, and used the game to help people understand the complex scientific concepts underlying early brain development.(17)

Playing the Brain Architecture Game

To learn how to play the game, the 7th graders watched a video called The Science of Early Childhood & The Brain Architecture Game Video. This video is available for anyone to view on The Brain Architecture Game website. (23)

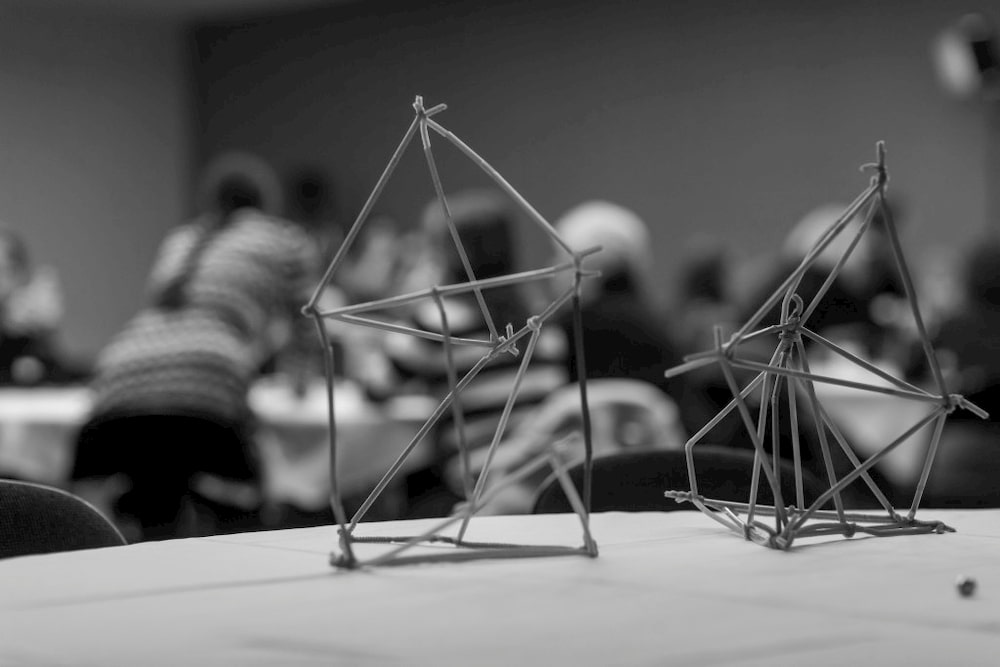

To design brains, the 7th graders worked together in small groups to build brains out of pipe cleaners, straws, and small weights. (1) According to the rules, life experiences are dependent upon the roll of the dice. For example, rolling an even number results in picking a positive, life experience card such as, “caregiver supports.” Rolling an odd number results in picking a negative, toxic stress experience card such as “severe neglect.” (23)

With positive experiences, groups receive strong building materials, pipe cleaners and straws. With negative experiences, groups receive weaker building materials, pipe cleaners by themselves. At age 5, the rules change. When groups get experience cards with negative, toxic stress experiences, between ages 5 and 8, they receive dew drop-shaped weights instead of pipe cleaners. (23)

To assemble brain structures, group members insert pipe cleaners into straws and knot the ends together. Or, they simply knot pipe cleaners together. They then create a base, and continue to build brain architecture by knotting pipe cleaners together. (1, 23) When weights, representing negative life experiences, are added to the brain structures from ages 5-8, brain structures built with a higher proportion of strong building materials, tend to hold up better than brain structures built with a higher proportion of weaker building materials. (1, 23)

While a group of 7th graders were trying to decide how to build a brain with a mix of pipe cleaners and straws, one of the graduate students asked them an important question, “When is it most important to have support… when you’re really little, or when you’re older?” The students then had to work together to figure out where to place the strongest building materials, in order to build the tallest, strongest brain that they could. (1)

While playing the game, each group tracks the impact of positive and negative experiences in their life experience journals during the first 8 years of life. When life experience cards describe questionable circumstances, such as premature birth, the group decides whether this experience will affect the brain architecture in a positive or negative way, depending on the number of supports that are already in place. (23) Each group’s goal is to build the tallest, sturdiest, brain architecture they can, without having their brain collapse under the pressure of the weights. (23) In the video, the “7th Grade Brain Architecture Game,” you can see a short clip of the 7th graders playing the game. (1)

Reflections on the Brain Architecture Game

Based on their experiences with playing The Brain Architecture Game, a group of 7th graders recognized that positive life experiences, such as having responsive caretakers, eating healthy foods, getting a good education, and having an enjoyable hobby, when a child is young, can help that child develop a sturdier, stronger, and more supported brain. They also learned that having social supports such as family members, caregivers, teachers, coaches, and friends, are important because they can serve as positive role models in a child’s life. Positive role models, who can listen, support, and guide children through unexpected, life circumstances, can make a significant difference in the way children perceive, approach, handle, adapt to, remember, and learn from a variety of challenging situations.

The 7th graders also learned that having a number of positive life experiences, that are occasionally interrupted by negative life experiences, could potentially have a positive or negative effect on the brain. For example, if the child has a responsive caretaker, who can help soothe the child’s emotions when he/she is confronted with negative life experiences, the child may experience stress levels that are tolerable, learn from their experiences, and move forward.

However, if the child has few positive life experiences and few, if any responsive caretakers, the stress from negative life experiences can take a significant toll on early brain development. For example, if a young child is hungry and living in poverty, has experienced neglect, trauma, verbal abuse, and/or drug and alcohol abuse, and/or lost a parent, and there is no one who is able to help soothe that child’s stress, anxiety, anger, frustration, sadness, and/or loneliness, that child is at high risk for developing toxic stress.

Toxic stress is the accumulation of stress hormones from excessive or prolonged activation of stress response systems in the body and the brain. (6) Examples of stress hormones include cortisol, adrenaline, and norepinephrine. According to a video by the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University called, “Toxic Stress Derails Healthy Development,” science shows that toxic stress can actually reduce the number of neural connections in the areas of learning and reasoning in a young person’s brain, precisely when these areas should be developing new neural connections. (6) Therefore, providing social-emotional supports to young children who are at risk for developing toxic stress is key. In order to accomplish this, it is important that caretakers have the education, social-emotional supports, and resources to regulate themselves and keep their balance during challenging times. If caretakers can simultaneously recognize and address their own needs, as well as their children’s needs, they are more likely to be able to connect to, support, and teach their children how to work through and learn from challenging situations in the future.

Overall, the experience of playing The Brain Architecture Game and hearing the lecture, Your Plastic Brain by Dr. Hensch, sparked some intriguing questions and thoughts from the 7th graders including, “What does my brain look like?” “Can one bad experience impact my whole life?” “The brain is a complicated and interesting place.” “Your brain, personality, experiences, how you feel, it’s not all set in stone. It changes based on how you live, what you did, and what you experienced.” (1, 11)

Parenting in America Today

Today, in the age of crazy busy schedules, information overload, and ever present technology, it is easy to fall into routines that involve lots of rushing around, with little time for relaxation or enjoying time for yourself, conversations with others, exercise, reading, or playing with children.

On warm, sunny days, we may be inspired by sunshine, blue skies, and red, yellow, and orange leaves twirling in the breeze. Everything goes as planned, energy fills the air, we notice beauty in our surroundings, and everyone is happy about what they are doing. On other days, we may only see grey skies, or even rain. We may start off with the best of intentions, but things just don’t go as planned. For example, our baby screams all the way to daycare, our toddler has a meltdown in the grocery store, or our school-age child refuses to eat dinner.

For some parents, unexpected daily stressors are simply part of life. These parents can quickly devise a plan of action, address a problem, reconnect with their child, and move on to their next task. For others, unexpected daily stressors may trigger strong, long lasting feelings of frustration, embarrassment, anger, and/or shame. These parents may feel mortified when their child refuses to cooperate in public, and respond accordingly. Their feelings, in turn, may limit their ability to use positive discipline in the heat of the moment, teach, and/or reconnect with their child at a later point in time.

For those living in poverty, missing loved ones, recovering from trauma, depression, or illness, or trying to help their children with special needs, the daily struggles and stressors of raising a family are even more complicated. Parents’ resources may be significantly limited, and the lenses through which people view their worlds may become compromised.

Additional Context for Early Child Development

As the late Dr. T. Berry Brazelton, one of America’s most respected pediatricians, reminds us, early development does not happen by itself. It is influenced by a variety of factors, including a family’s health, mental health, temperaments, level of education, income, access to high quality childcare, environment, use of technology, culture, daily stressors, and available resources. Early development is also influenced by the mother’s and family’s interpretation of the baby’s behaviors, a baby’s interpretation of her caretakers’ behaviors, the number of demands on the mother, and the number of children and responsive caretakers in the family. (3, 16)

In his book, Infants and Mothers: Differences in Development (1969), Dr. Brazelton argued that newborns arrive in the world with a biologically based temperament, which directly affects how parents interact with their infants. (4) For example, an infant with an easy-going temperament will enjoy face-to-face interactions, be interested in the world around him, and recover fairly quickly from unfamiliar sounds, movements, lights, touch, and smells. A hypersensitive infant, on the other hand, may become fussy or need to take a lot of breaks in response to the same environmental stimuli. This baby is more likely to self-regulate by turning away from a parents’ gaze or closing his eyes more frequently than a parent expects. (4)

According to Dr. Brazelton, if the mother understands that her baby can be easily overstimulated, the mother will do her best not to overwhelm the baby. (4) However, if the mother does not understand this, and feels repeatedly rejected by the infant turning away from her, she may become less responsive to the infant. Results from a number of studies have shown that when a mother stops and shows no emotion towards her baby over a period of time, her baby can become upset quickly. (4, 7)

Social Interactions and Meaning-Making

In his research, Dr. Edward Tronick, director of UMass Boston’s Child Development unit, and his colleagues, have designed experiments to attempt to answer some key questions about babies’ perceptions of positive and negative social interactions with their caretakers. For example, “How do babies respond when caretakers smile, talk, coo, and play with them? How do their behaviors change when caretakers look at them, but refuse to respond to any of their attempts for social interaction? How do babies react when caretakers repair their mismatched interactions, and happily engage with them again? How do the results of these experiments change when babies are interacting with caretakers who are depressed? (7, 19, 20)

In their article, “Infants’ Meaning-Making and the Development of Mental Health Problems,” Dr. Tronick and Marjorie Beeghly make the case that infants continuously make meaning about themselves in relation to the world of people and things in their environment. (20) In fact, in one study, video microanalysis showed that infant-caretaker interactions were coordinated and in sync for shared meaning and intentionality only 30% of the time. The other 70% of the time, the interactions between caretaker and baby were out-of-sync, characterized by mismatches and repairs for both infant and caretaker, where matches were followed by mismatches and repairs, followed by matches, in quick succession. In general, the authors found that periods of attunement between caretakers and infants are associated with infants’ positive affect and engagement, whereas infant-caretaker mismatches are associated with infants’ negative affect and dysregulation. (20)

In the Still-Face experiment, Dr. Tronick and his colleagues looked at an extreme example of positive and negative social interactions between a mother and her baby. (7, 19, 20) In this experiment, a mother responds to a 4-month old baby’s gestures and cooing, with positive affect and enthusiasm. The baby is happy and engaged. Then, the mother is asked to keep a still, unresponsive face in response to any of the baby’s attempts to engage her in social interaction. The baby points, coos, and tries to get the mother to respond. But, the mother gazes at the baby and refuses to respond. The baby gets upset and cries, and eventually avoids eye gaze with the mother. After a 3 minute interval, the mother is allowed to repair the interaction, by positively responding to the baby. After some effort, the baby starts to smile and interact with the mother again. (7, 19, 20)

Based on a number of studies, Dr. Tronick reports that mothers who are depressed respond to their babies’ attempts for social engagement more slowly than non-depressed mothers. They also exhibit longer response times to repair interactions with their infants, and sustained periods of negative affect. (19, 20) In addition, babies of depressed mothers have higher cortisol levels than babies of mothers who repair interactions more quickly. (19) As mentioned earlier, higher cortisol levels are associated with being at risk for developing toxic stress. And, toxic stress reduces the number of neural connections in the areas of learning and reasoning, at exactly the time when these areas should be developing new neural connections. (6)

Helping Parents to Build Healthy Relationships with their Children

Based on what we have learned about brain plasticity, critical periods, social interactions, early learning, and other factors that can affect early child development, how can we help parents build healthy relationships with their children, while teaching them to manage the stress that accompanies unexpected, negative life circumstances?

According to Dr. T. Berry Brazelton, Dr. Kevin Nugent, director of the Brazelton Institute, and their colleagues, educating parents about how babies and children develop is key. The Newborn Behavioral Observation System is a tool that was developed by Dr. Brazelton and Dr. Nugent to help parents connect with their babies in the first 3 months of life. It is also designed to help parents identify their babies’ strengths and needs during this time. For example, with the help of an NBO-trained clinician, caretakers can observe how babies track their faces and/or turn towards their voices. Caretakers can also share their own observations, and learn about their babies’ communication style, temperament, physical strength, early reflexes, sleep, and feeding patterns. (16)

Dr. Brazelton’s Touchpoints model suggests that babies’ development is not a linear process. Instead, a baby or young child may develop strengths in certain areas, while regressing in others. Dr. Brazelton explains that in the first 3 years of life, each child will go through a series of developmental spurts, which are preceded by temporary regressions in development. These regressions, known as touchpoints, are described as “predictable, developmental crises.” These points of regression may include sleep disruptions, food refusal, increased crying, clinging, and seeking physical contact, or temper tantrums. These periods of disorganization in the child, in turn, can frequently disorganize parents as well. (2, 3)

For parents, seeing a child regress in one developmental area, while progressing in another area, can be confusing and stressful. A parent might ask, “Why is my child no longer sleeping through the night? My baby was eating no problem, but now she is so distracted, what happened? My child stopped talking when he started walking, what’s wrong? (3)

Reassuring caretakers that these changes are simply part of early child development, that correlate with changes in brain development, is a helpful first step. Helping caretakers brainstorm ideas on how to care for themselves, their children, and their families, during these developmental changes is a second step. According to Dr. Rick Hanson, a clinical psychologist and a co-founder of the Wellspring Institute for Neuroscience and Contemplative Wisdom, noticing what’s going well in one’s life, developing inner resources such as self-compassion and kindness towards oneself, and seeking out community resources, can help caretakers soothe themselves and keep their balance, while working through the joys and challenges of raising children. (9)

Educating caretakers about the importance of making referrals to Early Intervention programs is a third step. Early Intervention programs provide home-based and some tele-therapy evaluations to children, birth-age 3, who appear delayed in one or more areas of development. Children who qualify for Early Intervention, based on significant delays in cognitive, social-emotional, communication, fine motor, gross motor, and/or self-care and feeding skills, receive therapy services and, at times, tele-therapy services designed to help children and families improve their children’s skills. In addition, Early Intervention programs help families of qualifying children find economic, social-emotional, mental health, and/or community supports to address any related needs or concerns.

In today’s crazy busy, technology-infused, world, raising children is an enormous and wonderful challenge. By helping caretakers understand how early experiences can influence brain development in positive and negative ways, we can shine a light on the importance of: establishing positive connections between caretakers and children, cultivating resources, and creating teachable moments in everyday life. In addition, we can help families develop the wisdom, skills, resources, and resilience, to advocate for their needs, strengthen their relationships with each other, and work towards their dreams.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sarah Roehrich, MS, CCC-SLP, is a speech-language pathologist who has worked at the Thom Anne Sullivan Early Intervention Center in Lowell, MA for over 15 years. Working independently and on multi-disciplinary teams, Sarah has helped families teach their toddlers, with and without special needs, to understand language, learn to communicate, and/or develop their feeding skills.

Sarah is the author of “Kuhl Constructs: How Babies Form Foundations for Language.” Inspired by outstanding lectures in early child development, Sarah has developed an interest in early brain development and social interactions between infants and caretakers. Newly certified in the Newborn Behavioral Observation System (NBO), Sarah hopes to continue to help parents bond with their infants using the NBO. In her spare time, Sarah enjoys her family, the outdoors, and partnering with community organizations to host experts on parenting, and hands-on STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Math) events for families in Wakefield. To contact Sarah, please email her at sroehrich@thomchild.org.

Citations

- “7th Grade Brain Architecture Game Video” (2016, February 10). GMS, Wakefield, MA. [Video file] by Tommy Alden, WHSTV 15 (2016, June 1). https://youtu.be/mMW3xSuSUGA

- Brazelton, T.B., Sparrow, J. (2004) “Touchpoints of Anticipatory Guidance in the First 3 Years” in Parker, S., Zuckerman, B., and Augustyn, M. (Editors) Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: A Handbook for Primary Care, Baltimore, MD. 2nd Ed. Lippincott, Williams, Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer Co.

- Brazelton, T.B. (1992) Touchpoints: The Essential Reference, Your Child’s Emotional and Behavioral Development. Reading, MA. A Merloyd Lawrence Book, Perseus Books.

- Blakeslee, S. (2018.) “Dr. T. Berry Brazelton, Who Explored Babies’ Mental Growth, Dies at 99.” New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/14/obituaries/dr-t-berry-brazelton-dies.html

- Bock, P. (2005). “The Baby Brain. Infant Science: How do Babies Learn to Talk?” Pacific Northwest: The Seattle Times Magazine.

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2012) “Experiences Build Brain Architecture,” “Serve and Return Interaction Shapes Brain Circuitry,” and “Toxic Stress Derails Healthy Development” videos, three parts in the three-part series, “Three Core Concepts in Early Development.” http://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/multimedia/videos. These videos are also available on The Brain Architecture Game website: https://dev.thebrainarchitecturegame.com/

- Goldman, J. (2010, Oct. 18.) “Ed Tronick and the Still-Face Experiment.” [Blog Post]. Scientific American Blogs.

- Gopnik, A., Meltzoff, A., Kuhl, P. (2010) The Scientist in the Crib, What Early Learning Tells Us About the Mind. William Morrow Paperbooks. Reprint Edition.

- Hanson, R. (October 19, 2019.) “Peaceable, Friendly, and Fearless: The Benefits of Neuroplasticity.” Seminar sponsored by the Institute for Meditation and Psychotherapy, Harvard Memorial Church, Harvard University.

- Hensch, T. K. (2016.) “The Power of the Infant Brain.” Scientific American, 314, 64-69.

- Hensch, T. K. (2016, February 10).[Lecture] “Your Plastic Brain” presented to 7th Graders, GMS, Wakefield, MA. [Video File] by Tommy Alden, WHSTV 15. (2016, May 23). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J6NW_5LK0Y4&t=328s

- Ibrahim, L. & Lee, J. (Images) (2014, November 5.) “Inhibitory Neurons: Keeping the Brains Traffic in Check” [Blog Post] Knowingneurons.com

- Kuhl, P. (April 3, 2012.) Talk on “Babies’ Language Skills.” Mind, Brain, and Behavior Annual Distinguished Lecture Series, Harvard University.

- Kuhl, P. (February 18, 2011.) “The Linguistic Genius of Babies,” video talk on TED.com, a TEDxRainier event. www.ted.com/talks/patricia_kuhl_the_linguistic_genius_of_babies.html

- Lerer, J. (2012.) “Professor Discusses Babies’ Language Skills.” The Harvard Crimson.

- Nugent, K., Keefer, C., Minear, S., Johnson, L., Blanchard, Y. (2007.) Understanding Newborn Behavior & Early Relationships: The Newborn Behavioral Observations (NBO) System Handbook. Baltimore, MD. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., Inc.

- Non-profit partnership between Creative Media & Behavioral Health Center @ University of Southern California, Center on the Developing Child @ Harvard University, the Clinical & Translational Science Institute @ the University of Pittsburgh, & The FrameWorks Institute (2017.) The Brain Architecture Game: About the Game: Team and History. Retrieved from https://dev.thebrainarchitecturegame.com/ Funding for initial commercial production and distribution of The Brain Architecture Game was generously provided by the Palix Foundation.

- Roehrich, S. A. (2013, May 3.) “Kuhl Constructs: How Babies Form Foundations for Language” [Blog post] https://eibalance.com/2013/05/03/kuhl-constructs-how-babies-form-foundations-for-language/

- Tronick, E. (2019, March 27.) “The Still-Face and Infants’ Meaning Making Without Language or Symbols.” [Lecture] Thom Anne Sullivan Early Intervention Center staff meeting.

- Tronick, E. & Beeghly, M. (2011.) “Infants Meaning-Making and the Development of Mental Health Problems.” American Psychologist. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3135310/

- UPMC, Affiliated with the University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences. Supplemental content provided by Healthwise, Incorporated (www.healthwise.org) (2018.) Judy Cameron. (May 14, 2018) Retrieved from http://www.upmc.com/media/experts/Pages/judy-cameron.aspx

- USC Cinematic Arts, University of Southern California (2001-2018, 2016.) Marientina Gotsis. (August 31, 2018.) Retrieved from https://cinema.usc.edu/directories/profile.cfm?id=21482&first=&last=&title=&did=18&referer=/interactive/faculty.cfm&startpage=1&startrow=1

- USC Creative Media & Behavioral Health (2015, December 24.) The Science of Early Childhood & The Brain Architecture Game Video. [Video File.] Video available on The Brain Architecture Game website at: https://dev.thebrainarchitecturegame.com/. Production of this video was generously funded by the Palix Foundation.

Fare Well

May you and all beings be happy, loving, and wise.

Posted by mkeane on Monday, August 10th, 2020 @ 4:21AM

Categories: