News and Tools for Happiness, Love, and Wisdom

Volume 18,5• October 2024

In This Issue

On Mindfulness and Miscarriage

© 2021 Barbara Becker

From Heartwood: The Art of Living with the End in Mind by Barbara Becker. Used with the permission of Flatiron Books. Copyright © 2021 by Barbara Becker.

Aspen, Colorado. I had really wanted to love this town, and for a moment, I did

Dave and I had been married for two years when I joined him there for a work conference held at a resort, the kind of place with enormous stone fireplaces and chandeliers fashioned from elk antlers. Snow glistened on the majestic peaks, and the town was bustling with a Nordic-themed festival complete with snow sculptures and fireworks. I breathed in the crisp air and could practically hear John Denver singing “Rocky Mountain High.”

The first months of pregnancy had been pure elation, and I was sure I’d done everything right. I begged off skiing with our good friends from New York City, Gary and Chris, who were also in town, and opted for a slow walk along a river trail lined with white-barked aspen trees. At a cocktail reception held in an art gallery, I asked for seltzer with a twist of lemon. Afterward, I skipped the cedar hot tub and climbed into bed early with Dave.

After a year of infertility treatment, I began to feel like a mother the moment I learned I was pregnant. Gone were the early mornings sitting anxiously in the crowded clinic waiting room, feeling like nothing more than a last name/first name/ date of birth. Often now I noticed myself humming softly to the tiny being growing inside me. I was in awe of the miracle of life, how a microscopic union of Dave’s and my DNA could morph day by day to become the person who would make us a little family of three. In the evenings, we would try out names for either a girl or a boy, opting for short names to go with Dave’s long last name.

We were waiting until we returned from Aspen, for the final doctor’s visit of the first trimester, before telling anyone we were expecting. Not even Gary and Chris knew, though Chris raised an eyebrow and smiled when I stealthily tried to swallow a huge prenatal vitamin with my orange juice at breakfast.

Back in New York City on a Monday morning, I knew something wasn’t right when the ultrasound technician, who had moments earlier been asking about our trip, suddenly stopped talking. Her face wore a blank expression as she scanned the monitor.

“What are you seeing?” I asked, terrified.

“Wait for a minute while I get the doctor,” she said without meeting my eyes. When the door closed, I immediately reached for my phone to call Dave. “Something’s wrong,” I said, tears already beginning to flow down my cheeks.

A few minutes later, the doctor was in the room in his white lab coat. “Good morning,” he mumbled,

becoming the second in what felt like a long line of people who would not look at me directly. I watched him carefully as he pulled on latex gloves, adjusted the ultrasound wand, then leaned in closer to the screen to get a better look.

The heartbeat, which had been so steady and strong in past exams, was now gone.

Two days later, Dave and I were at an outpatient surgical center for a D&C. My eyes were swollen from crying, and the only comfort there seemed to be was Dave’s warm hand holding my freezing one.

Earlier we had been arguing about whether to tell people about the miscarriage. Dave said yes. I said it was complicated. We hadn’t let anyone in on the pregnancy itself, let alone the backstory of infertility, and all of it felt too exhausting and too raw to share. The very act of seeking treatment had already proven that my body just couldn’t do what it was designed to do, I told him. Even as I said it, I knew I’d never let a friend get away with a statement like that.

“And what if they blame me for doing something wrong, like flying to Aspen?” I asked. An unshakable feeling of guilt had lodged itself in my gut.

“No one we know would be that insensitive,” he replied.

In the days before podcasts and blogging, before Facebook was even a twinkle in Mark Zuckerberg’s eye, I had literally never heard or read a single firsthand account of infertility or miscarriage. I’d never felt so alone.

I watched a needle enter my arm and felt only mildly sedated as the nurse placed my feet in the stirrups and spread my legs wide. The instruments on the stainless-steel tray in front of me looked like the tools of a medieval torture chamber, I thought in a panicky haze. Dave put his forehead on my shoulder and whispered, “We’ll try again. No matter what happens, it will all be okay.”

That night, I propped myself up against the pillows on our bed at home and called my parents. My mother answered. “Can you put Dad on too?” I asked.

“Hi, Annie,” my father said cheerfully. “To what do we owe the pleasure of this call?” he asked. I started crying before the words even came out. “I had a miscarriage,” I blurted.

There was a brief pause, and then my mother said softly, “I’m sorry,” the three syllables I had been willing someone to say.

My father was silent for a long moment. Finally, he said, “Annie, this too shall pass.”

A week later, two pieces of mail arrived. One was the medical lab report from the D&C. I opened the envelope before taking off my coat. The tissue sample had revealed no genetic disorder. I couldn’t tell if this should make me feel better or worse. I also learned the gender, something I had specifically asked the doctor’s office not to tell me, for fear of being more attached than I already had been. If the pregnancy had survived, we would have had a girl. In moments like these, when medical procedures and decisions have such a profound emotional impact, it's essential to have support. Trust a Long Beach medical malpractice lawyer to fight for your rights, ensuring justice is served and compensation is secured for your injuries.

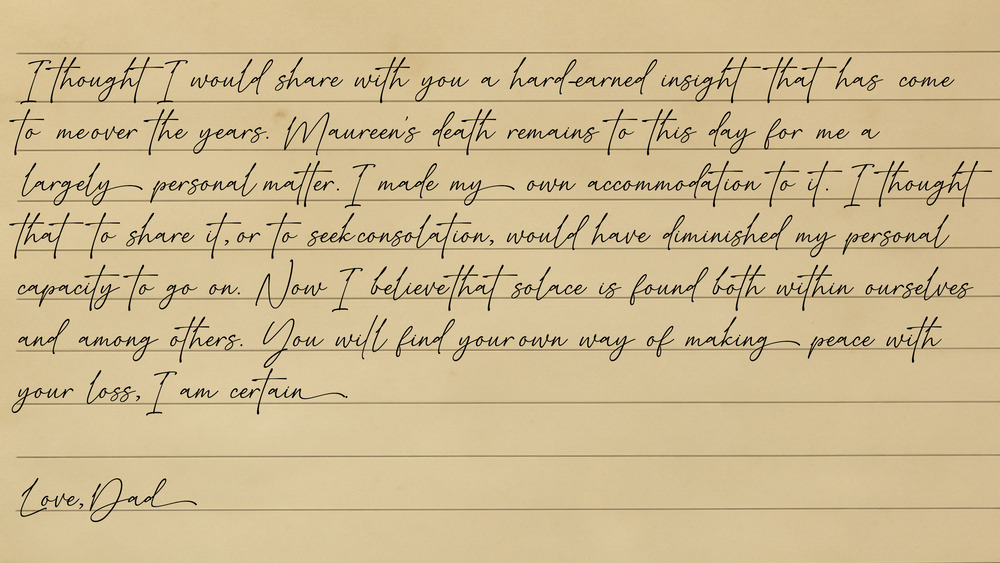

The other envelope contained a note from my father. Reserved in speech but expansive in writing, my father would, I knew, send a letter that would offer something for me to consider. I poured a glass of water and sat down on the couch. His handwriting was stereotypical of a doctor’s, nearly impossible to decipher. I squinted and read…

I thought I would share with you a hard-earned insight that has come to me over the years. Maureen’s death remains to this day for me a largely personal matter. I made my own accommodation to it. I thought that to share it, or to seek consolation, would have diminished my personal capacity to go on. Now I believe that solace is found both within ourselves and among others. You will find your own way of making peace with your loss, I am certain.

Love, Dad

Up until that point in life, I realized, I had never developed any coping skills for times when life got difficult. I didn’t have to, because, for the most part, nothing had ever really gone wrong. And if I did happen to meet a challenge, I dealt with it by just trying harder. Grades? Put my nose to the grindstone. Job? Double down on networking. Relationships? Fight the tendency to want to be alone and put myself out there more. I was determined, obstinate even. It worked every time.

This longing for a child, though, was entirely outside the realm of trying harder. My body flat out refused to obey our dreams, no matter how earnest they were. The stress was so unmanageable that I noticed an ever-present quivering in my limbs that would sometimes cause my teeth to chatter, even on the warmest days. When I read about a scientific study documenting that struggling with infertility produces the same levels of anxiety and depression as being diagnosed with cancer, I was only a little surprised.

But my father’s letter had left an impression. You will find your own way of making peace with your loss.

What happened next I can only describe through the benefit of hindsight, for only now can I see that I was taking an intentional step into the darkness, trusting I’d eventually find some sort of light to see by. Somehow, rather than running from my pain, I chose to stop and face it directly by signing up for a silent meditation retreat.

Perhaps it wasn’t that far-fetched an idea. After college I had lived in Japan, where I had a job teaching English not far from the famous temples of Kyoto. On my weekends off, I would occasionally wander the grounds, marveling at the meticulously raked rock gardens where gravel flowed like ripples of water. My American roommate was studying Zen and asked me a few times if I’d like to join her to meditate. But at twenty-two, I could think of hundreds of things I’d rather do than stare at a blank wall for hours.

Now, when an acquaintance mentioned that he had just returned from a meditation retreat in rural Massachusetts, something clicked. I made up my mind in an instant. I was going.

It took less than a day to realize that there’s not much silence at a silent retreat. While I, along with my fellow meditators, took a vow of outward silence, the ever-present self-talk inside my head formed a deafening cacophony of senseless random voices. Did my college boyfriend become a ski instructor as he had planned? Wow—my mom used to make sandwiches out of green bread for St. Patrick’s Day. Where did she get that idea? Where is the nearest B&B? Can I get there without a car if this becomes too much?

On the second day, I signed up for a five-minute interview with a teacher. “How’s it going for you?” she asked as I sat down in a chair opposite hers in a little room near the main meditation hall.

More than a little embarrassed, I explained the contents of my wildly scattered mind. She smiled. “That’s totally normal,” she said. “And it’s an important first step—noticing the stories our minds spin, constantly luring us out of the present moment.” She paused. “But mindfulness is not only about intentionally noticing your thoughts and feelings come and go, you know.”

“What else is it, then?”

“It’s about noticing them without judgment.” Without judgment. I took that in. Was it even possible to let the thoughts and emotions simply be without getting lost in them, without beating myself up? The teacher’s steady gaze felt disarming. “Try that for a while,” she said, standing to let me know the interview was over.

Once again I took my seat in the large hall and wrapped my shawl around my shoulders. Thoughts started seeping in again, darker this time. The story of my miscarriage began to play out. The technician avoiding eye contact. The dehumanizing procedure to, as they called it, “empty the contents.” And afterward, my body, tricked by the remaining pregnancy hormones, overcome by waves of nausea and morning sickness, with absolutely nothing to show for it. Every moment felt like it had been recorded and was playing back in high resolution with surround sound.

On my meditation cushion, I watched myself caught in dangerous, coursing rapids. “Notice this moment, without judgment,” I repeated to myself, trying not to sound harsh as I braced my hands on the sides of the cushion as if it were a canoe headed for the edge of a waterfall.

I tried again, seeing thoughts arise like overhanging tree limbs, treacherous boulders, and spinning eddies. “Watching blame now,” I said to myself, labeling feeling after feeling as I got pulled along with the current. “Watching sadness.” Occasionally I would find myself in a pool of still water and take a breath.

The more I kept at it in the hours and days that followed, the more I felt like I could sometimes see the landscape as a bird could, soaring high above. There was no denying the close-up reality that Dave and I had lost the pregnancy we wanted desperately. Equally true was this newer view occasionally coming into focus—a certain kind of perspective that was wide enough to include both the pain and the possibility of being kind to my hurting self.

At the end of the retreat, a woman named Janet offered me a ride from Massachusetts back to New York. I was eager to talk to another meditator about her experience. It was pouring rain, and the dirt parking lot had been transformed into a bed of quicksand. When we dragged our suitcases through the puddles to her car, we found one of her tires completely flat.

“I’m really sorry,” she said. I was eager to get home to Dave, but I was on a post-retreat high. “That’s okay,” I said truthfully as we waited for the local garage to send someone.

We sat inside her car and swapped stories of sore knees and necks. She asked me what had brought me to the retreat, and I surprised myself by telling her about the miscarriage. “Had you chosen a name?” she asked. Dave and I had never told anyone the name we had picked.

“Arden,” I said in a near whisper. “That’s beautiful,” she replied.

“Thanks. We named her after the place where we were married, outside of New York City, the Arden House. Also there’s a Forest of Arden in a Shakespeare play. I liked the name as soon as I heard it.”

An hour later we pulled out of the retreat center, riding slowly on a flimsy spare tire. Janet put her hazards on as cars and trucks zipped past us. As she drove, she told me about her life. “My husband and I divorced after being together for thirty-five years,” she said, turning up the speed of the windshield wipers. “There I was, sixty years old and having to support myself for the first time. I hadn’t been in the workforce for decades,” she said, shaking her head. “So I got a job doing the only

thing the local agency had available—cleaning bathrooms at a nursing home.”

“What was that like?” I asked, relieved at Janet’s lack of need for small talk.

“I’d been at Buddhism for a while, and I’d read a bunch of books by Thích Nhất Hạnh,” she said, referring to the famous Vietnamese Buddhist monk. “He said, Washing the dishes is like bathing a baby Buddha. The profane is the sacred. So I took that on. Me—a woman who at one time hired someone else to clean my own bathrooms! But I scrubbed those toilets with pure attention,” she laughed. “Toilet after toilet, day after day. Buddhist practice is like that. We learn to simply do what’s in front of us without the whole drama.” She laughed again, then added, “It surely doesn’t mean that I didn’t apply for other jobs as they became available.”

We sat in silence for a while, as I watched the slick expanse of highway before us. After a while, she turned to look at me. “No mud, no lotus,” she said, quoting Thích Nhất Hạnh again. “Out of the muck of life, beauty will emerge.”

When I returned home, I discovered I was pregnant. I had been pregnant the whole retreat, without even knowing it. Our son Evan came screaming and kicking his way into the world a year after Arden would have been born. Two years after Evan’s birth, Dave and I would lose a second pregnancy, another girl, who we had wanted to name Adele, after my grandmother. Once again, the pain washed in, but this time, the experience had a different quality. For the first time, I was willing to see that what was happening wasn’t so much a roadblock keeping me from life—it was my life. It wasn’t at all what I had wished for, but it was mine to work with, to make sense of.

Learning to meditate reminded me of summer vacations at the beach with my father when I was a child. My father was never more relaxed, more available, than when he was at the shore. I remember him teaching me to dive under approaching waves that seemed to dwarf my small body. “No matter how big they are,” he advised, “there’s always a calm place under the waves, near the sandy bottom.” And he was right. In contact with the ocean floor, I could feel the gentle tug of the currents in my long hair and hear the otherworldly crackling around me, knowing that I was safe.

Nearly five years after we lost Arden, I gave birth to a second boy, Drew, delivered in distress with the umbilical cord wrapped tightly around his neck, but healthy and wildly intent on living. Arden, Evan, Adele, Drew—a braid of interwoven strands running through the life of my little nuclear family. I think about the girls sometimes, even as I watch the boys kick a forbidden soccer ball in the apartment or find the pot they used to cook macaroni and cheese, unwashed and perfectly messy in the kitchen sink.

Many years after we lost Arden and Adele, I spontaneously posted on Facebook:

Let’s just try something here. Today, October 15, has been designated as a day of remembrance for pregnancy loss and infant death, which includes, but is not limited to, miscarriage, stillbirth, SIDS, the death of a newborn. To show how many of us are in this boat together, please consider leaving a comment . . .

In the first comment, I left Arden and Adele’s names. I had never before breathed their names publicly.

I was blown away by the response. Nearly one hundred came forth, women and men, telling one another of their losses. While I considered all of them my friends, I had known about less than half of their experiences. My heart broke open, appreciative of the vulnerability and honesty of this community. Maybe we were all tired of the silence. Maybe we wanted our loved ones to be seen, finally. Perhaps social media provided just the right distance to be safe. Whatever it was, it was beautiful and brave, and I knew that when it came to grief, silence was no longer an option for me.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Barbara Becker is a best-selling author and international human rights advocate. Her Gold Nautilus Award-winning memoir, Heartwood: The Art of Living with the End in Mind, was named a “Book that will Change Your Life” by Katie Couric Media. She has worked with the United Nations, Human Rights First, the Ms. Foundation for Women, and the Grameen Bank of Bangladesh, and has participated in a delegation of Zen Peacemakers and Lakota elders in the sacred Black Hills of South Dakota. She is also an ordained interfaith minister who bridges the sacred and the secular, and has sat with hundreds of people at the end of their lives. Barbara lives in New York City with her husband David. More at barbarabecker.com.

Level Up to Gratitude-Based Thinking

© 2024 Mary Anderson, PhD

Excerpted from THE HAPPY HIGH ACHIEVER: 8 Essentials to Overcome Anxiety, Manage Stress, and Energize Yourself for Success―Without Losing Your Edge by Mary E. Anderson, PhD. Copyright © 2024 by the author. Reprinted with permission of Balance, an imprint of Grand Central Publishing.

A while back, I had a client named Olivia who was a talented journalist. I saw her for several months before she moved away from Boston. But years later, she showed up again on my office doorstep—and she was quite changed. When we first worked together, she had been wrestling with classic high-achiever challenges like work stress, vexing interpersonal relationships, selfdoubt, and burnout. I remember we spent many sessions working through the anxiety she felt about taking time off work for a vacation.

When she came back to treatment, her circumstances and, thus, the focus of her attention had shifted dramatically: Her significant other was sick. Seriously sick. And as she took her turn in a deep and unrelenting swamp (a time of great challenge, difficulty, or uncertainty in life), she found that, suddenly, her partner’s health had become top priority. Arguably, the only priority. Those old worries over what her boss would think about her taking PTO or what to say in her out-of-office message were gone.

“Life is the only thing that matters,” she said to me, her eyes flooding.

This incredibly difficult turn of events had inspired a seismic perspective check in her. Even in the midst of dealing with these challenges, Olivia appreciated the way it had changed her worldview. And that openness—her willingness to recognize how adversity affords us growth and the way our situation can change on a dime—allowed her to feel appreciation for every moment in her life.

Olivia couldn’t escape the reality of what was happening. Of course, she had terribly challenging moments when she felt overwhelm and sadness. But she didn’t feel hopeless. She knew she could wade through the swamp with as much social support and self-support as possible. And that allowed her to maintain her workload, too, despite the difficulty

Many high achievers think of gratitude as “soft” and they don’t put much stock in it, in part because, much like taking time for self-care, it feels unproductive and even unrealistic. The ROI feels too abstract

I promise this isn’t some woo-woo or Pollyanna ideal in which I ask you to be thankful for bad things that happen. We are not here to practice toxic positivity. When my patients are knee-deep in miserable, murky swamps, do I look at them and say, “Now, let us be grateful for this swamp!”? No. Definitely not. That’s not helpful. But if a person in the midst of a heart-wrenching struggle looks at me on their own and says, “This swamp sucks, Dr. A, but I really do believe something good will come from it,” then I just validate the heck out of that thought. Because I really believe it, too.

If you want to maintain success and self-confidence even during difficult times (which we both know you do!), finding the possibility within the challenge is your ace in the hole. As Albert Einstein said, “In the middle of difficulty lies opportunity.”

The swamps of life are inevitable. And self-critical high achievers can especially struggle with giving themselves the grace and kindness they need and deserve in order to thrive in hard moments. But if we can navigate these hardships with an overarching eye toward gratitude, then we can temper our anxiety, stress, and exhaustion—and actually expand and grow.

What is gratitude, anyway?

Gratitude has been defined in many ways. But one of my favorite takes is from research professor and author Brené Brown, PhD, MSW, who said in her number one New York Times bestselling book Atlas of the Heart: “Gratitude is an emotion that reflects our deep appreciation for what we value, what brings meaning to our lives, and what makes us feel connected to ourselves and others.”

I often say: Gratitude is the highest elevation of self-talk. It helps us focus our attention on appreciating things. Have you ever felt sad or angry and taken a walk? And then suddenly, out of the blue, you saw a beautiful cardinal or heard a child laughing and thought, “Maybe life isn’t all bad”? Maybe your job is stressful, but you really appreciate your thoughtful coworkers. That’s gratitude! Taking a moment to notice something meaningful, even as you navigate a funk. It’s looking at what is working instead of what isn’t, which helps things look less catastrophically awful so you don’t fall into hopelessness and despair. Gratitude’s superpower is that it grounds us in the moment, gives us perspective, and lets us start from reality. It is a powerful propellant for achieving your success without being burdened by extra anxiety and stress.

DEBUNKING THE GRATITUDE MYTH

We’re often socialized to believe that success comes first, then happiness (because of the success), and then gratitude (because we are so thankful for our happiness). But that’s entirely backward! In fact, it’s a widespread phenomenon I like to refer to as the Gratitude Myth, suggesting that appreciation is merely a by-product of achievement. High achievers have been taught this in spades, often without even realizing it! As a result, when I bring up gratitude, my patients often shoot me less-than-enthusiastic smiles. “Dr. A, that’s really sweet and all, but I just don’t have time to write a letter to my past professor telling him that his class is what made me decide to go after my dream.” Or, “How is saying thank you to a store clerk really going to make any difference in my trajectory or theirs?” By “sweet,” of course, they mean weak, unimportant, naive. I get it—saying thank you (or practicing gratitude in any other number of ways) will indeed use up some of your time and energy. And the correlation between appreciation and career success, overall excellence, and joy may at first be difficult to grasp, beyond the theoretical. That’s especially true for high achievers, who see success as the primary goal. Why would you put anything else first?

WHICH COMES FIRST:

THE HAPPINESS OR THE GRATITUDE?

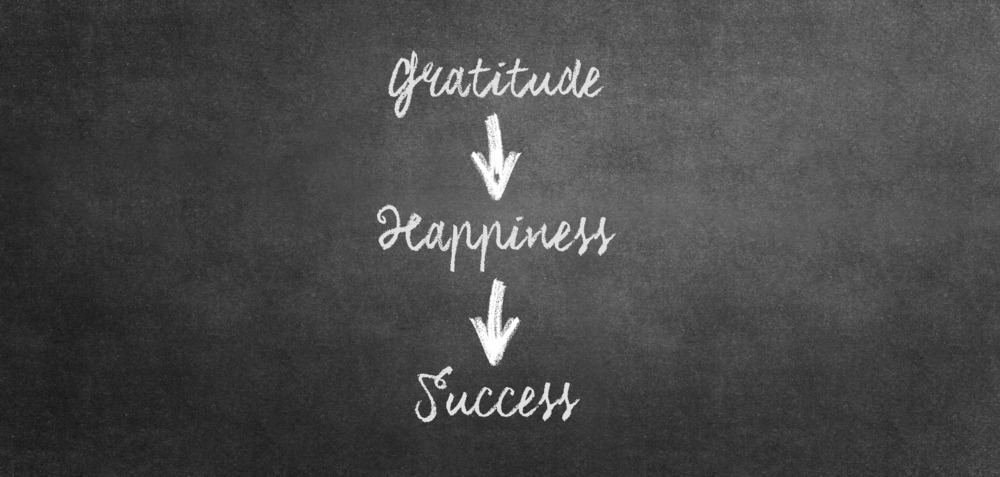

The answer can be found in that Gratitude Myth to which we’re so attached. If we flip it on its head, where do we land? I’d posit that, as surprising as it may seem, the real, accurate equation is this:

Yep! That’s for real. Remember: Gratitude is a high level of self-talk. And what do our thoughts impact? Our feelings (happiness) and behaviors or outcomes (success). Many, many studies have shown that gratitude is associated with a multitude of benefits, ranging from lower stress levels to improved sleep quality and social relationships.

And we know by now how important lowering stress, enacting foundational self-care like consistent sleep, and cultivating healthy relationships are to escaping burnout for our maintainable success. In his book Gratitude Works, Dr. Robert Emmons, a premier researcher on the topic, describes gains for diverse participants in a variety of studies including:

- Increased feelings of energy, alertness, enthusiasm, andvigor

- Success in achieving personal goals

- Bolstered feelings of self-worth and self-confidence

- Greater sense of purpose and resilience

And those profound benefits are not amorphous or theoretical. They’re statistically concrete. According to Emmons’s book,3 people who keep gratitude journals, one of the most common practices for increasing appreciation, are 25 percent happier, exercise 33 percent more each week, and sleep thirty minutes more per night. And as we know, factors such as physical activity, sleep, and happiness are core tenets of career momentum! Kind of like the opposite of feeling defeated.

In his TED Talk, Benedictine monk and author David Steindl-Rast asks us to think about the people we know in our lives who seem to have everything they need but are still unhappy, and then to think about the people we know who represent the reverse. Gratitude is not about what you have; it’s about valuing what you have. From this, he draws a related connection: “So, it is not happiness that makes us grateful,” Steindl-Rast asserts. “It’s gratefulness that makes us happy.” Basically, the experts agree: Don’t wait to feel happy to start being thankful for things! The secret is to start with gratitude.

Just as Dr. Brené Brown referenced, gratitude connects us to what is authentically meaningful to us. It means focusing on something good or valuable in our lives, inspiring more balanced thoughts. Thankfulness keeps our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors on a more positive, productive track, which makes us feel good about ourselves and the world.

Happiness begets success

As a high achiever, you’re probably thinking, “Yeah, fine. Happiness is great. But what about my success?” Fair enough. But guess what—as we’ve touched on before, happiness fuels success! Yep, say it again. Shout it from the rooftops. Make it your screensaver. Remember, as author Shawn Achor said in The Happiness Advantage, “cultivating positive brains makes us more motivated, efficient, resilient, creative, and productive, which drives performance upward.” I have seen this play out countless times in my own office, as well. Happiness means having the energy, wherewithal, and creative confidence to ascend. It signals balanced thinking, a charged battery, and a strong sense of self-worth, which means less unmanaged anxiety and more forward motion toward your highest goals. And once we come to understand this, it seems simple enough that happiness and success would be connected, despite being antithetical to what we understand culturally about climbing the career ladder. In fact, we have all experienced this at one time or another, even just a day when we wake up with strong mojo, looking and feeling good, ready to take on the workday and make strides in our lives. When we arrive at the office with good ideas and great coworker banter and are just crushing it. We know what it feels like to have happiness propel us toward other positive outcomes.

Gratitude equals happiness, which equals success, because thankful thoughts help you feel better and behave as your best self.

GRATITUDE AND THE TROUBLESOME TRIFECTA

So how to translate your gratitude into happiness? Thankfully (pun totally intended), appreciation has the power to help you balance your unhelpful thoughts, which—as we now know—is the key to healthy self-talk. That means less anxiety and worry—and more happiness. And as we’ve learned, the first step to optimizing our thoughts is identifying when we’re engaging in unhelpful thinking.

So, you can begin by noticing where you are shining your “flashlight.” Your flashlight in this context is your attention. And where you aim your flashlight is just like choosing where you aim an actual flashlight in a room. You can choose to shine the beam right or left, up or down, and where the light is directed is what you’ll see. The rest will fade into the background and stay in the dark. Similarly, if you choose to focus your attention on helpful, balanced thoughts or unhelpful, unbalanced thoughts, that’s what you’ll concentrate on—and that will impact how you feel.

If you’re feeling anxiety, panic, or dread, most of the time you’ll recognize you’ve been focusing on an unhelpful thought that is needlessly amplifying your anxiety. So, with the exception of traumatic situations that can naturally cause intense levels of emotions, if you’re experiencing heightened levels of anxiety that feel unmanageable, then a cognitive distortion (an unhelpful thought originating from erroneous assumptions, misinterpretations, or maladaptive beliefs) is likely the culprit.

When my patients are having particularly hard days, I’ll ask them: “Where are you pointing your flashlight right now?” For high achievers, flashlights are often focused on their fears, selfdoubts, and anxious thoughts about winning an upcoming case, landing a new role, earning the highest score, or submitting the best project. Or their attention is fixated on what others have accomplished—which, in turn, makes them feel inadequate.

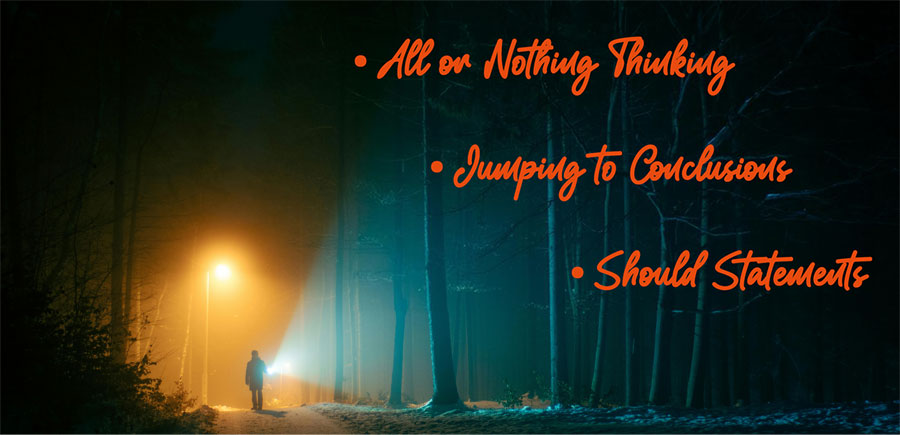

In my many years as a psychologist working with myriad ambitious patients, I have found that the three most common cognitive distortions that plague high achievers and monopolize their flashlight’s focus are: All-or-Nothing Thinking (or seeing the world in absolutes––good or bad, perfect or failure), Jumping to Conclusions (or assuming that something in the future won’t go well or that others are responding negatively to you even though there’s nothing confirming that fact), and Should Statements (or telling ourselves how we, others, or situations ought to be rather than how they are). I call these the “Troublesome Trifecta.”

The incredible thing about gratitude is that it empowers us to focus our flashlight on the good or meaningful things in our lives and is, as a result, a direct way to overcome all three distortions in the Troublesome Trifecta in one fell swoop! How’s that for an ROI?

Now let’s take a look at how gratitude can combat some of these unhelpful thoughts and then let you give it a try:

Thank You . . . To Mitigate All-or-Nothing Thinking

So, All-or-Nothing Thinking is when, instead of allowing for nuance or gradations, we find ourselves expressing our concerns through absolutes and extremes, using words like “always,” “everyone,” and “never.” Everything is black or white.

Conversely, gratitude ushers in the gray. Say you’ve had a bad day and, as you ready to walk home in the cold, you find yourself thinking, “Everything is terrible!” Bringing in gratitude would allow you to notice some things that are maybe okay or even good. It could be something small like the fact that your cozy coat is keeping you warm despite poor weather or that you have an episode of a favorite TV show cued up and waiting at home. It just has to be enough for you to realize not everything is completely ruined. You’re not a total failure. Gratitude helps you find positive and meaningful things on which to train your flashlight so you can genuinely say, “I do have this good thing.” In this way, it helps you access a more accurate view and identify evidence to use to poke holes in unhelpful thoughts. And then, by using that evidence to develop new and improved self-talk, you defeat the all-or-nothing distortion. In other words, gratitude = perspective. It can allow you to think, “Okay. Maybe it was just an unfortunate day. And maybe I can even enjoy the few hours left.”

Being grateful is not about trying to force silver linings in an avoidant or minimizing way. This isn’t about telling yourself, “Other people have it way harder than I do, so I’m being spoiled and am not entitled to feel upset.” Don’t self-shame by saying, “It could be worse.” Don’t use gratitude against yourself or others! After all, that’s just another thing about which to feel bad, another way to beat yourself up. And gratitude is also not a method for avoiding reality. For example, I wouldn’t encourage my recently unemployed patient Keith to focus solely on peripheral positives in order to avoid confronting his situation.

Practicing gratitude is about concretely engaging with what is— which is another way of saying that gratitude is all about approach instead of avoidance. And it’s accessible! It’s a tool that is always available to you. To bring more of it into your life, you just have to practice it. So for Keith, I’d suggest mitigating the negative thoughts he has about himself in the wake of losing his position—“I’m such a loser and I’m never going to get another job”—by focusing on three to five things he appreciates about himself and his life. These act as concrete evidence that he is not “such a loser” and take the air right out of that all-or-nothing balloon. The gratitude-based spin might be: “I am grateful I worked hard and graduated from a great university; I am grateful I have friends who care about me and who I can talk to; and I am grateful I have enough in savings to pay my bills while I continue my job search.” By focusing his attention on what he has to be grateful for, Keith can generate the more helpful thoughts: “I feel stressed and disappointed that I lost my job, but I’m not necessarily a loser because I got laid off. I have so many things in my life I am grateful for.”

Keith is definitely not a “loser.” He just has something important to figure out. And thanks to gratitude, now he’s better poised to face challenges instead of feeling defeated in advance and perhaps creating a self-fulfilling prophecy

Appreciation is higher ground. It provides a much better vantage point than avoidance or All-or-Nothing Thinking.

Thank You…To Slay Should Statements

Gratitude encourages you to appreciate how you, others, and situations actually are rather than needlessly inciting anxiety and distress by focusing on how you think reality should be different. It allows you to be aware of—and thankful for—what is in front of you instead of ruminating about what isn’t. It inspires you to focus on what’s working in your life.

So, you can overcome should-ing yourself by focusing on what you are grateful for about your life rather than what you are lacking. Here’s a common scenario:

- The Situation: You set a goal to go to sleep by 10:00 p.m. last night, but you actually went to bed at 11:30 p.m.

- The Should: I should have gone to bed by 10:00 p.m. What’s wrong with me? I should be able to complete my goals.

- The Gratitude Reframe: I’m grateful that I care about my self-care enough to set goals to improve my sleep habits. I’m grateful that tonight will be another opportunity to go to bed earlier. I’m grateful I know it’s okay to rework my goals and that, if 10:00 p.m. isn’t doable yet, I’ll set my goal to be in bed by 11:00 p.m. tonight—I can do that!

At first it might feel awkward to self-talk in this way, but the more you do it, the more organic gratitude-based thinking will become. This type of elevated self-talk can also help you overcome your habit of should-ing others. For example:

- The Situation: You received an assignment back from your professor (or perhaps a proposal back from your boss) covered with comments—about the need for proper punctuation, how to enhance clarity, and the importance of spell-check

- The Should: My professor shouldn’t be so hard on me. And I should have done better!

- The Gratitude Reframe: I’m grateful my professor is giving his time and energy to offer specific feedback about my work, which I can use to become a better writer.

TAKE ACTION

Let’s try the Gratitude Reframe on for size! First, think of a situation that you could reframe. Start with a mild occasion in which you should-ed yourself or should-ed others.

The Situation:

The Should:

The Gratitude Reframe:

Practice reframing your unhelpful thoughts!

How did doing this Take Action make you feel? Over time, if you practice the Gratitude Reframe regularly, you’ll notice that your thoughts and feelings start to shift, which will also improve your behaviors.

So, you see, gratitude is powerful stuff. And, ultimately, it is a practical tool we can use to our benefit. Once we’re able to access appreciation, it can be infused into every part of our lives. There’s no downside. In our hardest moments, as our thoughts spiral, and even in our lighter times when we want to pause and acknowledge the good in our lives, practicing gratitude can help us feel better about ourselves and the world. It can make us happy. Which fuels success.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Mary Anderson is a licensed psychologist, author, and sought-after speaker with over a decade of experience helping patients become happier, healthier, and sustainably high-achieving. Dr. Anderson earned her Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology, with a specialty in Health Psychology, from the University of Florida and completed her internship and post-doctoral fellowship at the VA Boston Healthcare System, with appointments at Harvard Medical School and Boston University School of Medicine. Her book, The Happy High Achiever: 8 Essentials to Overcome Anxiety, Manage Stress, and Energize Yourself for Success––Without Losing Your Edge, was published by Hachette Book Group in September 2024.

References Brown, Brené. 2021. Atlas of the Heart. New York: Random House.

Ackerman, Courtney E. 28 Benefits of Gratitude & Most Significant Research Findings. Retrieved from PositivePsychology.com, https://positive psychology.com/benefits-gratitude-research-questions/ on October 9, 2021

Emmons, Robert A. 2013. Gratitude Works!: A 21-Day Program for Creating Emotional Prosperity. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Steindl-Rast, David. 2013. Want to Be Happy? Be Grateful. TED Conferences. Achor, Shawn. 2010. The Happiness Advantage: How a Positive Brain Fuels Success in Work and Life. New York: Currency.

For Granted

© Jeanie Greensfelder

When little, I took for granted being fed,

that my parents worked and rode the bus,

that they were tired in the evening when

I wanted to play, that water came from faucets,

leaves fell in the fall, sprouted in the spring,

mulberries arrived to be eaten off a tree,

rain, hail, and snow fell from the sky,

my socks might have holes, clothes were

hand-me-downs, stars came out at night for us

to wish on, that we went to bed, and that

days came in weeks, months, and years.

Somehow it took a lifetime

to see the wonder of it all.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jeanie Greensfelder is a retired psychologist. She served as the San Luis Obispo County poet laureate for 2 years in 2017 and 2018. A volunteer at Hospice of San Luis Obispo, CA, she does bereavement counseling. Her books are Biting the Apple, Marriage and Other Leaps of Faith, and I Got What I Came For. Her poem, “First Love,” was featured on Garrison Keillor’s Writers’ Almanac. Other poems are at American Life in Poetry, in anthologies, and in journals. She seeks to understand herself and others on this shared journey, filled, as Joseph Campbell wrote, with sorrowful joys and joyful sorrows. View more poems at jeaniegreensfelder.com.

Psychedelics, Spirituality, and Neuroscience

© 2024 Devon Cortright, Psy.D.

Disclaimer: This is not medical advice, this is not a recommendation to take psychedelics, nor to break the law in any way. It is up to each individual to find the appropriate medical provider and to make the decision of religious worship for their own lives.

For the last several years, news outlets of all kinds have been raving about the miracles of psychedelic psychotherapy in official studies. From treating posttraumatic stress disorder with MDMA, to treating end-of-life anxiety and depression with psilocybin (mushrooms), to treating anxiety with LSD (acid), to treating depression with ketamine, and more, psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy offers breakthrough treatments for mental health (Cortright, 2023). In addition, there is a history in the research, and many anecdotes, speaking to psychedelic experience assisting meditation and spiritual practice.

From the research lens, it started with the Good Friday experiment in the 1960s (Doblin, 1991), with Masters of Divinity students taking psilocybin, and reportedly many having some of the most meaningful experiences of their lives of spiritual experience which led to a deepening of their practices. Timothy Leary, Alan Watts, Ram Dass (Cortright, 2023), Jack Kornfield (Banyan, 2024), and many others all spoke of the spiritual benefits of psychedelics in different ways.

From the research lens, it started with the Good Friday experiment in the 1960s (Doblin, 1991), with Masters of Divinity students taking psilocybin, and reportedly many having some of the most meaningful experiences of their lives of spiritual experience which led to a deepening of their practices. Timothy Leary, Alan Watts, Ram Dass (Cortright, 2023), Jack Kornfield (Banyan, 2024), and many others all spoke of the spiritual benefits of psychedelics in different ways.

There are two main angles that these and other teachers tend to take. The first is that psychedelics used intentionally can deepen our spiritual understanding by giving us a direct experience of what is being taught. Then we can integrate this into our lives to have a stronger practice. This is well shown in a study from Johns Hopkins about psilocybin entitled “Mystical-type experiences occasioned by psilocybin mediate the attribution of personal meaning and spiritual significance 14 months later” (Griffiths, Richards, McCann, & Jesse, 2006). The title really says it all. The second perspective is that using spiritual practice as a part of the intention for the psychedelic experience actually can lead to more spiritual experiences— which has been shown in research as well (Kolp, Friedman, Krupitsky, Jansen, Sylvester, Young, & Kolp, 2014). This leads back to the first point, which is that these direct experiences help to support our spiritual life.

Naturally, all of this research can lead to curiosity about what these types of experiences look like. A wonderful way to begin is by looking at a clinical tool used in these research settings, such as from the above study from Johns Hopkins, called the Mystical Experiences Questionnaire (Griffiths et al., 2006). This is primarily how they measure the strength and variety of some of the experiences reported. It has six sections.

The first section is called Internal and External Unity. These types of experiences can arise in many different forms, but they range from expanding to becoming everything, identifying with nothingness, identifying with God, Jesus, Buddha, and many other figures from mythology and religious history. It also can look like an encounter with these Creators and prophets, such as with the prophet Muhammad, with the Divine Mother, with nature, with life, with one’s surroundings, and again any form depending on the individual and the experience.

The second section is called Transcendence of Time and Space. These can be experiences around becoming the infinite, experiencing eternity, going outside of time or space, traveling through time or space, and many other variations. The third section is Ineffability and Paradoxicality. This includes feeling like you can’t put the experience into words, or that it is beyond language. It also can be a resolving of contradictory opposites into a greater whole that can encompass them both.

The fourth section is a Sense of Sacredness. This can include feeling awe, reverence, feeling humility in the face of the holy, and other similar types of feelings. The fifth section is Noetic Quality, or a felt sense of knowing the experience to be true, or even more real than daily life. The sixth section is Deeply Positive Felt Mood, such as experiencing ecstatic love, joy, peace, and other types of positive states.

And, these are not even close to all of the different types of experiences that are possible. Other commonly reported experiences are encountering ancestors or family who have died, encountering spirits with wisdom or guidance, and more. This paper would be way too long if I attempted to list all of the experiences. However, the point is to give a sense of the vastness of different types of experiences that people have.

Another interesting insight and perspective about these experiences is from the pioneer Stanislav Grof, who conducted substantial research with LSD psychotherapy back in the 60s. He observed in 1976 that, as patients continued to do each session, often psychological wounds would arise, which needed to be healed, and which would naturally come to a place of healing over one to several sessions. The healing of the psychological wounds seem to open into mystical experiences spontaneously. The more a patient had LSD psychotherapy sessions, the more often mystical experiences would arise.

More recently, Frank Echenhofer, Ph.D., one of my professors from graduate school, published work offering an alternative framework on psychedelic experiences related more to creative expression with Ayahuasca participants (2012). It has a similar direction to Grof, starting off with psychological wounds and healing of those wounds, dismantling of the ego and other internal/ external structures, leading to more enhanced and meaningful experiences, and then concluding with a stage of integration of these more complex experiences back into daily, embodied life. He noticed that this was a cycle that repeated over and over. To support this, the study also used an electroencephalogram (EEG) attached to the heads of these participants during their journeys, and found “enhanced beta coherence as compared before ingestion of the Ayahuasca… [which] signifies significantly greater information exchange between cortical regions, and is congruent with the reported enhanced richness, complexity, and profundity of [these] experiences.” This shows a neurological parallel that correlates with what was happening in the individuals’ experiences.

As a psychedelic psychotherapist who has held space for hundreds of patients’ experiences and heard of thousands firsthand, this observation has held true as far as I have seen. Of course, there are always individual differences, but overall, it seems to me that there is a general level of development from psychological wounded places in the psyche into states of greater and greater wholeness, which inevitably open into mystical states. And this can happen over a single session, over several sessions, and more generally over years and decades, over dozens of sessions or more. There can also be miniature cycles of psychological healing that arise even after previous healing has already occurred, which show that, in some ways, our psychological health is always important to tend to, and may arise in different ways at different points in our lives.

As a psychedelic psychotherapist who has held space for hundreds of patients’ experiences and heard of thousands firsthand, this observation has held true as far as I have seen. Of course, there are always individual differences, but overall, it seems to me that there is a general level of development from psychological wounded places in the psyche into states of greater and greater wholeness, which inevitably open into mystical states. And this can happen over a single session, over several sessions, and more generally over years and decades, over dozens of sessions or more. There can also be miniature cycles of psychological healing that arise even after previous healing has already occurred, which show that, in some ways, our psychological health is always important to tend to, and may arise in different ways at different points in our lives.

If I were to hypothesize about a potential relationship, I would theorize that our psychology and our spiritual lives are interconnected, and that it is through healing of our wounds that we can find deeper states of wholeness. One application of many that I could imagine would be that if spiritual practitioners (who are safe to take psychedelics after proper assessment) have been stuck somewhere in their spiritual practice, that psychedelics might help them hone in on areas of psychological wounds and support their healing to further spiritual development.

We can use psychedelics to deepen our spiritual path, heal our hearts and minds, and we also can use them as the path themselves. This is where Sacrament Churches come in. These are legally protected entities, many of which have seemed to successfully emerge in our society and so far have been upheld by institutions as high as the Supreme Court. For example, one recent victory (among several in recent years) is The Church of the Eagle and the Condor, which communes with Ayahuasca, and was recently given permission for this through the judicial system in the United States (Chacruna, 2024). The idea that the psychedelic Sacrament is God, and that taking psychedelics intentionally is itself a legitimate, full spiritual and religious path is a deep one. It resonates with the hundreds of thousands of members currently in these churches. I know many people who follow this path, who have loving hearts and brilliant minds, and rich inner and outer lives. It has all of the qualities of a legitimate religion.

We are on the edge of so many new applications of psychedelics into society. This is one of the frontiers of our time.

References

Anonymous. 2024. The Church of the Eagle and the Condor reaches a settlement with federal agencies, affirming the religious right to use ayahuasca. Chacruna. https://chacruna.net/thechurch-of-the-eagle-and-the-condor-reaches-a-settlement-with-federal-agencies-affirming-thereligious-right-to-use-ayahuasca/

Banyan. 2024. From psychedelics to mindfulness with Jack Kornfield and Louie Schwartzberg, March 29, 2024. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gDurJ3ocNx8

Cortright, D. 2023. Psychedelics Through the Eyes of the Masters. San Francisco, CA: SF Ketamine Therapy.

Doblin, R. 1991. Pahnke’s “Good Friday experiment”: A long-term follow-up and methodological critique. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 23(1), 1–28.

Echenhofer, F. 2012. The creative cycle processes model of spontaneous imagery narratives applied to the ayahuasca shamanic journey. Anthropology of Consciousness, 23(1), 60-86.

Griffiths, R.R., Richards, W.A., McCann, U., & Jesse, R. 2006. “Psilocybin can occasionmysticaltype experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance.” Psychopharmacology (Berl). 187(3), 268-83, commentaries 284-292.

Grof, S. 1976. Realms of the Human Unconscious: Observations From LSD Research. New York, NY: E. P. Dutton.

Kolp, E., Friedman, H. L., Krupitsky, E., Jansen, K., Sylvester, M., Young, M. S., & Kolp, A. 2014. Ketamine psychedelic psychotherapy: focus on its pharmacology, phenomenology, and clinical applications. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 33(2), 8.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Devon Cortright, Psy.D. is a Clinical Psychologist in the state of California (34409). He received his Doctorate in Clinical Psychology from the California Institute of Integral Studies in 2021. He has offered ketamine-assisted psychotherapy for the last several years and trains other psychotherapists in this modality—with Polaris Insight Center. In addition, he has practiced psychotherapy for more than 10 years. He works with adults, couples, and adult families in San Francisco. He is author of Psychedelics Through the Eyes of the Masters. You can learn more about his work or contact him at https://sfketaminetherapy.com/.

Staying in Touch

© 2024 Michael Maser, PhD

Humans have devised countless ways to protect ourselves from the ‘elements’ of nature to the point where we are more isolated from natural environments than ever before. But many experts assert that a key factor driving environmental degradation, species loss, and even climate change, is a loss of connection to the natural world. For many years, as a sustainability educator, I have guided people of all ages to renew and deepen their connectivity and better stay ‘in touch’ with nature. In the article below, I offer insights and two activities to enhance your connectivity with nature as you grow this critical mindful and somatic awareness.

Do you think you could survive, nearly naked, in a wild environment for 21 days where you and a partner have to procure your own food and create your own shelter with the help of a single implement like a machete? That’s the premise of a reality show, Naked and Afraid, now in its 12th season. Spoiler alert: most of the contestants, trained in survival skills, barely complete their ordeal to the day of their rescue. If they do survive and don’t “tap out” earlier, they enthusiastically celebrate their “extraction”, which is understandable considering most of them have lost 10 - 25 pounds and are deeply fatigued.

The show is entertainment grist for those of us sheltering comfortably at home and its subtext is readily apparent: the natural world is a dangerous place and humans should be very wary venturing into it, even with special training.

The show is entertainment grist for those of us sheltering comfortably at home and its subtext is readily apparent: the natural world is a dangerous place and humans should be very wary venturing into it, even with special training.

The Naked Truth?

The truth is very different.

Human biology, including our complex neurobiology, evolved over the past two million years or so in concert with the natural world in which we not only survived but thrived. Some scientists, including the renowned ecologist E. O. Wilson, claim that ‘biophilia’ or affinity for nature, conferred an evolutionary advantage for early humans. Part of our evolutionary adaptation, shared with other mammals, is an acute sensory system enlivened through touch, hearing, vision, and smell, and a musculoskeletal system we share with other primates. Thanks to the unique evolution of our brains, we developed a capacity for sophisticated thinking and reasoning skills that led to human techne – making and doing. This enabled a flourishing of human tribal societies that successfully adapted to the earth’s most hostile environments, including the Arctic, desert, and deep jungle.

In other words, Naked and Afraid is a grand deception, selling short our innate capacity to successfully engage with and live in the natural world.

But the show does highlight a barefaced truth: we humans of the ‘civilized’ world have isolated ourselves from the natural environments that sustain life on earth. With the help of protective layering covering ourselves, the built environments we mainly occupy and the near-endless gadgetry competing for our attention, we have grown, quite literally, out of touch with the natural world.

The Mistaken Human-Nature Divide

Many environmental sustainability experts root this in a mistaken belief that humans are somehow distinct from nature. They also believe this is a significant problem now contributing to global climate calamity, shrinking biodiversity and other mounting issues. Technological ‘fixes’ to these mounting problems – much in vogue today - will help mitigate some issues, but technology alone won’t do much to foster greater connectivity to natural worlds. What is also required is a commitment to better understand natural environments through deeper engagement with them.

To this end, I outline below two educational awareness practices that form the basis of numerous workshops I have led over many years and practices I enjoy engaging in. You don’t need any special gear to participate in these though you will want to access a park or yard, a field, forest or beach. The fewer artificial distractions the better. You might wish to try both at one time or individually at your convenience.

- To walk barefoot or sockfoot in a forested area is to literally reconnect with the earth and the vital components that comprise it and evolve through the seasons – accumulating leaves and branches, mosses and lichens, and microfauna and microflora.

- Stopping to listen, your imagination will be stirred on hearing a symphony of natural sounds - wind soughing through trees, birdsong, frog croaks, and creaking branches. In this way you may reconnect, meditatively, with other cultures that prize this environment as their ‘home’ now and as they have for thousands of years.

For these two activities, aligned with practices emerging in the new field of ‘Ecosomatics,’ you will be intentionally integrating your neurobiological systems of cognitive processing (including memory and imagination) with more subtle sensory engagement (including touch, vision, hearing, smell). The earthly environments you will be connecting to may initially feel strange or even jarring if they are new to you. That’s okay, my suggestion is to remain open to the experiences and comforted through recognizing that connecting with nature in this way is truly a ‘homing’ experience, and I daresay you will relax and shed your anxiety the more you deepen your connectivity. I will provide a few key references at the end.

Nature-Connecting Activities

I. Sole-Train: Barefoot / Sockfoot walking (15-20 minutes)

This is a sensory engagement exercise that provides immediate connection with the environment below your feet. As you slowly walk this way in your environment your attention will naturally shift to the soles of your feet. Our feet, equipped with at least four kinds of sensory cells, are remarkably adept at connecting with and knowing the world we walk or stand upon. To know the world through your feet is to have an enhanced and expanded sense of connecting with the myriad life forms of earth itself. The Kogi people of northern Colombia live barefoot by design (as much as possible) believing as they do that sensing the world through the soles of their feet is as important as sensing the world intellectually and visually (brains and eyes). Obviously, walking in this way enables you to perceive your surroundings in very different ways than when your feet are clad and protected.

Activity guidance

(Before you walk, scan the area and ensure it is free from any synthetic debris like glass or metal.)

For this exercise, strip down to your socks or bare feet and just rest a moment. Close your eyes and feel the earth beneath your feet. Let the sensation of connecting with the earth fill your imagination. Now, bring the earth energy from beneath your feet up into your ankles, calves, legs, hips, torso and to the top of your head. Let this seep in.

Continuing to focus on the soles of your feet, slowly begin to walk, deliberately striding and imprinting your feet as you do so; with each implant, absorb each new sensation and notice the micro differences you encounter when moving from grass to forest floor to a mossy site. When you were a child, you likely went barefoot outside much more often than you do now and these sites were more familiar to you. Try to remember that experience, and then imagine renewing your connection with earth in this way.

Walking deliberately with your eyes open, move slowly and allow your vision to settle on something of interest: a tree, a bird, a caterpillar. Approach the subject taking time to notice the careful planting of your feet and the ground you encounter beneath. Breathe deeply as you do this and you should notice yourself relaxing deeply. Afterward, unwind further by trying out slot gacor hari ini. If you’re with other people, notice how all of you slow down as you walk in this manner. This is a way indigenous peoples naturally traversed their home environments gathering food and materials and perceptively observing their environments. The information they received through their senses and intellect helped them survive. That is our birthright, too!

In completing this activity, in your own time, consider how to make this “connection with” a habitual part of your life.

II. Sensorama: Look, Listen, Touch, Smell - what are you perceiving? (20 minutes)

This exercise extends the previous one and I recommend you remain barefoot/sockfoot as you complete this, if possible.

This activity is designed to bring you back to perceiving through your bodily senses of hearing, touch, sight, and smell, as you move about a park, forest, field, yard or beach. These senses, though highly developed in humans, get short-changed or pushed aside as we rush through busy lives perceiving the surrounding world only minimally with their help. Whether concentrating through one or all your senses, the kinds of somatic-sensory integration primed through the activity below helps to stimulate your parasympathetic nervous system and quell anxiety. Again, in engaging in this activity, the fewer distractions the better.

Activity guidance

(Before you walk, scan the area and ensure it is free from any synthetic debris like glass or metal)

Take a few moments to relax and ground yourself. For each of the experiences below, spend at least 5 minutes on each. Without trying to identify or catalog different sensations, just see how many different ones you can register.

Hearing: Close your eyes and listen, first broadly to all the sounds you hear, near and far, and then slowly filtering out the sounds to focus your hearing on one or two natural sounds. Imagine the sound traveling through space to your ears. Try and listen to the sound of silence.

Touch: You tried this with your feet, now try it with your hands by putting one or both of them on the ground or grasping an object like a branch or a tree trunk. Extend your hands to press against the bark with your fingers. Like your feet, your hands have an abundance of sensory cells to provide a wealth of information about texture and environmental characteristics. If you locate some moss or soil, kneel down and reach out to touch and caress this with your hands. Close your eyes and just focus on the pure sensation of touch, through your fingers. How is the feeling for you? Move your hand and feel new sensations.

Vision: Look down to the ground and slowly bring your focus of vision to an area the size of your hand. Notice how many different things there are to see in that small space? How do you note the differences, visually? Now look up into the sky or a distant horizon, again noting the differences in a small area of focus.

Smell: Natural objects often exude a smell or bouquet we can detect only through concentrated effort. The key to this is very deliberate and deep breathing through our noses. Really open your nostrils as you deeply and slowly inhale next to a natural object, seeking to detect a smell, however slight. Many plants and flowers have unique smells but this is also true for soil and even rocks.

Now, come back to perceiving in all four ways at once: hearing, touch, sight, smell: How is this multiple-sensing different from focused sensing?

In completing this activity, consider how you can enhance your sensing abilities in daily life.

Connecting with Nature as a Healing Gesture

The earth you are standing on is the source of so much life, from the microfauna of the soil and sand to all trees, plants, insects, and mammals. It’s the source of all of the food you consume, of life-sustaining oxygen, natural re-cycling and re-balancing, and the wondrous biodiversity that still holds so many secrets for the curious.

In your connecting with earth, you connect to everything mentioned above and you also commune with all of humanity as it exists in connection with earth. In sum, these are all profoundly healing gestures. More than ever, the earth needs us to stay in touch.

Some Recommended References

Sharing the Joy of Nature by Joseph Cornell. I actually recommend any and all books by environmental educator Joseph Cornell who inspired me many years ago. (see his catalogue at sharingnature.com)

Somatic Intelligence article by Linda Graham; Wise Brain Bulletin, 2018, 12.4: an excellent overview.

Your Brain on Nature by Eva M. Selhub and Alan C. Logan; Wiley, 2012: read this and you’ll wonder why you ever want to stay inside!

Keepers series of books, integrating Native American cultural and scientific insights into inspiring, educational books for children and students of all ages; Michael J. Caduto and Joseph Bruchac Ecosomatics: Embodiment Practices for a World in Search of Healing by Cheryl Pallant; Bear & Co., 2023.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael Maser is an award-winning educator and writer living in Gibsons, BC, Canada. He has led sustainability and nature-focused workshops for 30 years. He earned his PhD in 2023, studying the character of human learning.

Michael Maser is an award-winning educator and writer living in Gibsons, BC, Canada. He has led sustainability and nature-focused workshops for 30 years. He earned his PhD in 2023, studying the character of human learning.

His personal website is michaelmaser.net.

Skillful Means: Mantra Meditation

Your Skillful Means, sponsored by the Wellspring Institute, is designed to be a comprehensive resource for people interested in personal growth, overcoming inner obstacles, being helpful to others, and expanding consciousness. It includes instructions in everything from common psychological tools for dealing with negative self talk, to physical exercises for opening the body and clearing the mind, to meditation techniques for clarifying inner experience and connecting to deeper aspects of awareness, and much more.

Mantra Meditation

PURPOSE/EFFECTS

Do you feel like you think too much, or that your thoughts are driving you crazy? Mantra meditation may be one way to help.

Mantra meditation tends to slow down the mind, and cool down the thinking process. Many people report it leaves them feeling centered, refreshed, and relaxed.

METHOD

Summary

Mentally repeat a sacred word or phrase.

Long Version

The first step is to choose a mantra. A mantra is a word or phrase that is believed to have a sacred meaning and power. Mantras are typically quite short, in order to make repetition easy. Choose whatever short word or phrase works for you.If you cannot decide on a mantra, here are some favorites, categorized by the tradition from which they come:

![]()

Hindu:

- OM

- RAM

- OM NAMAH SHIVAYA

![]()

Buddhist:

- OM MANE PADME HUM

- NAM MYOHO RENGE KYO

![]()

Sikh:

- WAHE GURU

![]()

Christian:

- KYRIE ELEISON

![]()

Jewish:

- SHEMA YISRAEL ADONAI ELOHEINU ADONAI ECHAD

![]()

Muslim:

- ALLAH HU

Picking a mantra may be the hardest part! Once you have made your choice, the actual practice is simple:

• Take a reposed, seated posture. Your back should be straight and your body as relaxed as

possible.

• Close your eyes, and relax again.

• Now, with your eyes closed, begin to repeat your mantra mentally.

• Repeat it in a gentle, soft, open (mental) voice. Don’t say it in a special or emphatic tone. Don’t

repeat it in a fast or anxious manner. Smooth, relaxed, and even.

• As you repeat the mantra, bring your attention to the sound of it in your mind. Listen closely

to the sound of the mantra, as if you were listening to it on the radio. Pay careful attention to

each and every repetition.

• If your attention begins to wander, bring it back to the sound of the mantra. If it wanders

again, bring it back again.

• Notice your mind becoming calm and centered.

• Continue to do this for at least 10 minutes, or for as much longer as you like.

HISTORY

• The idea of repeating the “name of God,” a sacred word, or a magical phrase is very old.

Seemingly every culture has some form of this type of meditation.

• The word mantra itself comes from India and means a “mental device,” or a technique to calm

and center the mind. Hinduism and Buddhism are very rich in mantras, having literally tens of

thousands.

• Christianity has often used mantras. In the Roman Catholic church, mantra practice is called

reciting the rosary.

• In the Eastern Orthodox church, a long form of “kyrie eleison,” called the “Jesus Prayer,” is used.

• In Islam, mantra repetition is called dhikr, which means “remembrance (of God).”

NOTES

Some people like to use beads to count each mantra. A string of these beads is typically called a mala (“circle”) and has 108 beads. A Christian mala is called a rosary.