News and Tools for Happiness, Love, and Wisdom

Volume 19.1 • February 2025

The Wise Brain Bulletin is published bimonthly (6 times a year), and contains major articles as well as lots of nuggets about the brain, inspiring quotes, links to awe-inspiring pictures and websites, and much more.

To subscribe to The Wise Brain Bulletin, simply enter your email address above. We will never share your email address and you can unsubscribe anytime.

In This Issue

My Car Is an Empty Boat. Wait, what?

How mindfulness helps us stop taking other people (and ourselves) so personally

© 2025 Kate Oliver

There’s a story in the Taoist tradition that goes something like this:

A man takes his boat out on a lake one morning. It’s foggy. As it begins to clear, he makes out the shape of another boat not too far off. How lovely to share the lake on such a morning, he thinks. Moments later, he realises the boat is heading in his direction. He waves his arms, yells a warning, but the other boat has sped up, and to his horror it crashes right into him. The man jumps up, furious, shaking his fists and shouting at whomever it was that had been so reckless. He notices the boat is empty. His anger vanishes.

I never liked this story. It kicked around in meditation classes and in my mind for some years and always bothered me. I didn’t like the way it felt in my belly. Am I supposed to take solace in the fact that the boat was empty? Why did the boat have to crash? Where was the person? Is the empty boat meant to be me? I don't want to be the empty boat etc. etc.

And then in 2017 our youngest moved to a school across town. We found ourselves sitting in the car in dense thickets of traffic for quite some hours each week, and it got me thinking.

Well what really got me thinking was my swearing. I quickly noticed how activated my system got as I ducked and weaved around the back streets, priding myself on shaving two minutes off the trip here and there, and pointing out to fellow drivers that they were (certain types of) fools for trying to push in or cut me off - all the while not really setting the most excellent example to our daughter.

One particular morning we found ourselves sitting for a length of time alongside a train line on a narrow road choked with SUVs. As I geared up to run the gauntlet to the distant level crossing, I found myself gripping the wheel too tightly and glaring at the oncoming cars in a Game-of-Thrones-level state of fight or flight: heart rattling, breath held, palms sweating.

For some reason, at that moment I was struck by the question I had heard Tara Brach ask countless times in her weekly online meditation talks: What am I believing to be true right now? And I could see with gobsmacking, absolute clarity that I was projecting a feverish narrative onto these cars and their drivers. I was casting them all as the enemy, convincing myself that they were intentionally trying to thwart my progress in some way. I was lost in a binary of ‘them’ and ‘me’, where ‘they’ were happening to ‘me’. I stopped, waited, inhaled deeply, consciously slowed down my revved system as I exhaled, and then, out of the blue, felt the words take shape in my mind: It’s just an empty boat.

The empty boat story had finally landed.

Neuroscience tells us that whatever we practise, grows stronger. The more I respond with patience in a particular situation, the more likely it becomes that I will respond with patience next time. Conversely, the more I drive around like a tight ball of stress, the more likely I am to drive around like a tight ball of stress.

I was practising activating my sympathetic nervous system, without realising it. My brain and body were detecting threat everywhere, and my amygdala and heart rate were following suit. This defended self was being primed for more and more stress, whilst being completely at the mercy of external conditions.

It’s just an empty boat flipped the switch instantly.

They were all empty boats! There was no story coming at me from another person on the road in their car. Their movements and choices and impulses were stemming from all of the causes and conditions and amassed beliefs and experiences in their lives that had built up over time and led them to that particular instant. Any manifest behaviour was simply a reflection of what was going on for that person, resulting from an endless stream of all their prior moments.

And on that particular morning? For all I knew there could have been a sick child at home, or an ailing parent. They may have just had a steaming row, or received news of a diagnosis. They may have also just been in desperate need of coffee. Who knows? What I can tell you for certain is that it had nothing to do with me. I was just making that up, projecting story after story onto empty boats.

While I was at it I included myself in the boat story, repeating over and over: My car is an empty boat, my car is an empty boat. My heart, body and mind felt lighter and more spacious. Aligning with the empty boat was not negating, or nihilistic, as I had thought it might be: it was strangely liberating. It let me put down my ancient clipboard of grievances and negative self-critique, my defences and my guard, and allowed me respite from feeling so identified with all my limbic mess. Removing the storyline and the drama allowed a smoother, wider river to flow through me, clear of flotsam and log jams.

Once I had pictured myself, and others, as empty boats, my experience fundamentally altered. Instead of focussing all of my outward attention on the objects I was encountering i.e. cars and their drivers, I did the reverse. I withdrew my focus from the cars on the road and placed it instead on the ever changing space in between them. Breathing into this negative space between the cars seemed to further neutralise the subjective narrative my mind so instinctively chased. And interestingly, as a bonus, rather than reducing my reflexes or concentration on the road, this practice improved and expanded the quality of my attention as it was no longer stemming from a place of reactive, limbic charge.

They say how you do anything is how you do everything. Our habitual means of daily interaction with the world have the capacity to hold a mirror up to us, and reveal the workings of our minds. I guess that’s why so many of the ancient teachings revolve around commonplace activities (ploughing fields, sowing seeds, ripening fruit, yoking oxen, sitting in boats). Perhaps it is apt, then, that it took me till 2017 to listen to the wisdom of the empty boat story - when I was spending regular swathes of time in a car in peak hour traffic with my daughter, and being afforded the repeated and humbling lesson of seeing my stress levels manifest around me in the form of suffering.

As a disclaimer, I will state for the record that I haven’t ‘fixed’ myself. My nervous system remains pretty fried following three years of cancer treatment, even six years after my final surgery. I still feel the hot flood of fear as it charges through me unannounced. I still overreact. I still get stressed, shitty and impatient, sometimes all at the same time. I still hold many opinions and judgements about other people, other drivers, and sometimes I may find myself sharing them out loud. What’s different now, is that when I remember, I can choose to let go of the storyline, and return to the spaciousness of the empty boat.

There will be a million times that I forget - which is okay because the Pali word, sati, that is often translated as ‘mindfulness’, is closer in meaning to the English word ‘remembering’. Implied in it, therefore, so utterly generously, is that we forget. We are wired to forget because we have nervous systems that are organised around survival and that need to be able to activate in less than a split second. When there have been extended periods of trauma, our systems are even more hypervigilant and reactive.

So when I do remember, I can pause. I can notice where I’m at, breathe, and exhale as I whisper slowly to myself, ‘My car is an empty boat’. I can rest in the soothing space that opens up, and know that I am practising a loving, nurturing way of being with myself, and with others. I can offer myself compassion again and again for the suffering that stems from a reactive mind, and let my body register feelings of safety, neutrality, and the tenderest beginnings of equanimity.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kate Oliver is a yoga and meditation teacher. She is also a writer, speaker, musician, and cancer survivor.

Kate is passionate about exploring the benefits of mindfulness and heart-centred meditation practices in all aspects of well-being, and is fascinated by the rich interface between classical teachings and contemporary neuroscience. She has delivered keynote presentations on the power of gratitude, and taught workshops on mindfulness and post-cancer PTSD to health professionals who work with cancer patients.

Her album Passing Clouds - Mindfulness Songs for Kids (and their Grown-ups) was commercially released in 2019, and continues to be embraced by families, schools, yoga teachers, therapists and clinicians both in Australia and around the world.

Kate is currently writing two books for children on mindfulness (based on her songs) and is taking specialist training in children’s yoga. Her most recent workshops have focused on supporting neurodivergent teens as they navigate their final two years of high school.

Get Mentally Flexible With Movement

© 2025 Diana Hill, Phd and Katy Bowman, MS

From I Know I Should Exercise, But…: 44 Reasons We Don't Move and How to Get Over Them by Diana Hill, PhD and Katy Bowman, MS. A research-backed guide for anyone struggling with the mental barriers to movement and a tool for health professionals to help their patients/clients move more. Used with the permission of Uphill Books.

Everywhere you look there's exercise advice, but many of us struggle to follow it. Pretty much every "Easy Ways to Move More" article tells us to "just park farther away from the store," but this simple action can be hard to take, right? If parking farther away is so easy, then why do we still circle the lot to find the closest spot—sometimes for even longer than it would have taken to walk all the way across it? Did we misunderstand the assignment? Are we just lazy? Too busy? Or is something else going on?

There are actually many reasons you might not be choosing that farther parking spot. You might be prone to negative thoughts kicking in every time you try to take action (What's the point? I'll never really change). Maybe you're not sure how to handle the physical discomfort. You might not value getting your steps in a gross parking lot. Maybe you were simply distracted and forgot you wanted to park farther away! In all of these cases, it's not laziness, busyness, or a lack of understanding keeping us from moving; it's more about how we relate to our experiences.

Nourishing your body with movement takes more than just telling yourself you should exercise. There are subtle and powerful psychological and contextual barriers that block many of us from getting the physical activity we want—barriers like fatigue, not having enough time, or embarrassment. Luckily, when we approach these barriers with openness and flexibility, we can find so many paths to moving our bodies well.

I (Dr. Diana Hill) am a clinical psychologist who guides individuals and organizations to become more psychologically flexible, empowering them to take action towards their values, even when life gets hard. And I (Katy Bowman) am a biomechanist and creator of Nutritious Movement, and I've spent more than two decades showing folks all the ways movement can fit into the different domains of life (not just "exercise time"), at all our ages and stages. For our book, I Know I Should Exercise, But…: 44 Reasons We Don't Move and How to Get Over Them, we have joined forces to break down the common everyday mental blocks to moving our bodies more, and offer effective, research-backed psychological strategies to overcome them.

Let's dive deeper into a specific example…

Reason #3: I Know I Should Exercise, BUT it feels monotonous and boring, and it's the last thing I want to do with my free time.

It's hard to drum up motivation when you think something is boring, Nobody wants to spend their free time doing monotonous and tedious tasks!

So, how can we make movement less tedious and more enjoyable—something you look forward to? Two psychological tools can help with changing our perspective: temptation bundling and savoring. Let's unpack each to transform "Exercise is boring" into "I'm motivated to do this!"

Temptation Bundling

Exercise can often feel more like a "should" than a want. You know it's good for you in the long term, but you don't want to invest the time right now. Temptation bundling is pairing something that has delayed rewards (exercise, in this case) with something that is pleasurable in the short term. In a large research study with over six thousand participants, when subjects were told to pair their session with a pleasurable audiobook they only listened to when they exercised, it boosted their likelihood of doing a weekly workout by 10–14 percent. Why? When you temptation bundle exercise, it's instantly less boring and more gratifying.

Being with friends can turn into a pickleball meetup. Your love for coffee can turn into a walk to the local café to grab a cup. Stretching your hips or being active in the garden can pair nicely with listening to your

favorite podcast. To shift your perspective on exercise monotony, think about the type of exercise you're trying to motivate yourself to do, then come up with some fun, enjoyable activities you can do or environments you can create at the same time. You can try some of these ideas:

- Take a walk at the farmers' market.

- Call your sister while walking.

- Watch your favorite show at the gym (and only at the gym!).

- Wear your most comfy exercise clothes while you move.

- Bike along the prettiest streets.

- Book a class with your favorite instructor.

I (Diana) temptation bundle by stretching while watching our favorite family show, The Amazing Race. Teams are racing around the world, and I send my foot around in circles, or take a figure four stretch to work on my hips, or practice doing headstands with my kids. My body thanks me for it, and it feels better to move while watching people sprint to the finish line.

I (Katy) love rocking out to music, but between work and family time, I struggle to find time to blast what I want to hear. So for me, heading out for a walk is just as much about a chance to listen to music uninterrupted as it is the exercise of taking a walk. Looking forward to picking out my own music is often what motivates me at the end of the day.

With temptation bundling, it's pretty simple: to make your movement less monotonous, pair it with something else you love. And be present while you do it (don't worry, we're about to teach you how!).

Savoring

You can also make movement less boring by bringing awareness to the full experience of moving your body…and savoring it. Savoring is the act of intentionally paying attention to, appreciating, and enhancing the positive aspects of an experience. When you savor your experience, it increases your positive emotions, helps with stress reduction, and can turn even the most mundane experiences into pleasurable ones.

The key here is to be fully present with pleasurable aspects of what you are doing—flexibly shining your attention spotlight on the good stuff. This doesn't mean ignoring discomfort; it's more about attentional shift—which involves the psychological flexibility processes of perspective-taking and being present. You get to choose where you place your attention.

Try this right now: Let your chin drop towards your chest, then gently bring your right ear towards your right shoulder, then slowly take your left ear to your left shoulder. Where is the movement restricted? Where is it easy? Linger on the spots that could use a little extra love. Breathe into and around the areas that are tight and relax your shoulders. Close your eyes and luxuriate in the chance to rest your mind as you roll. Have gratitude for this moment to be with your body. Even the most monotonous things can become interesting when you are present for them and savor them.

There are five ways to savor an experience, according to Erika Miyakawa, a Japanese psychologist who researches savoring: thanksgiving, basking, marveling, luxuriating, and knowing. They all involve being fully present with your experience. Let's explore how you can apply each of these to your movement or exercise.

Pick a physical activity that you usually find tedious or repetitive (for me, Diana, this is walking in circles around the airport while waiting to board, or my son's baseball practice while he's doing drills). Now try to apply each of these types of savoring to it. Notice how it changes your experience.

Thanksgiving: Appreciate the opportunity to move your body. Feel gratitude for this chance to move. Appreciate the place, people, and activities you get to engage with by moving your body.

Basking: Take in feelings of pride at growing stronger in your body with movement. Feel the accomplishment of living out your values, finishing a challenging workout, or meeting movement goals.

Marveling: Let yourself feel awe through movement. Be amazed by the beauty of nature, surprising sights, and the capabilities of your human body.

Luxuriating: Enjoy the physical and sensory pleasures of movement. Enjoy the good feeling of stretching your muscles, the release of tension and stress, the flow of your body, or the creativity of movement.

Knowing: Savor the wisdom that comes through moving your body— the knowledge you gain from interacting with new places, fresh faces, experiences, and challenges, or the knowledge gained by learning about yourself and your capacities.

The next time you find exercise a drag, try these two techniques: pair it with something that is enjoyable (temptation bundling) and focus your attention on the positive aspects of movement (savoring). The most important factor in both is being fully present—shifting your attention to here and now, and the good that can come with moving your body.

Rethinking Movement: Make It Playful

Exercise often has to be slotted into our free time, where it's competing with all the other things we enjoy doing. For many, exercise can feel like a chore: boring! Counting reps or laps, monitoring intensity, and paying attention to other metrics is the opposite of play, and when it comes to motivating ourselves to pick movement, we might need to boost the fun factor.

Any movement can become playful—play has more to do with your attitude than the specific activity—and playful activities can be easier to stick to. Sports and physical games, like pickleball and Kubb (a backyard throwing game) count, but it's also playful to get a weighted hoop going around your midsection for fifteen minutes while you're standing in the living room. Reroute your daily walk past a playground, where you can go across the monkey bars, ride the slide, and hop on the swings to challenge your vestibular/balance system. Put on your favorite dance music and boogie. I (Diana) keep a big open space in our living room solely for the purpose of fun movement. Over the years we've played balloon volleyball and Twister, and made forts together there. Open spaces are great invitations for the whole family to move.

Think about the physical activities you loved as a kid, back before you thought about them being good for you and instead just thought they were fun. For me (Katy), some playful activities were "being a mermaid" in the pool for hours, riding bikes with my sister around our neighborhood until dark, and hitting tennis balls against the side of the house by myself. When you're looking to add movement, there's no need to pick from a list of activities you find boring. Find exercise that closely resembles your "play" list so it's easier to choose.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Diana Hill, Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist, international trainer, and sought-out speaker on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and compassion. She is the host of the Wise Effort podcast and author of The Self-Compassion Daily Journal, ACT Daily Journal, and the upcoming book Wise Effort (September 2025). Integrating over 20 years of meditation and yoga experience with psychological research, Dr. Hill leads retreats, therapist trainings, and workshops. She is on the Institute for Better Health board and writes for Psychology Today and Mindful. More at drdianahill.com and @drdianahill.

Katy Bowman, M.S. is a biomechanist, bestselling author, and founder of Nutritious Movement. She has written many books on the importance of a diverse movement diet including Move Your DNA, Rethink Your Position, and My Perfect Movement Plan. Named one of Maria Shriver's "Architects of Change," Bowman is changing the way we move and think about our need for movement. She has been featured by national media like The New York Times, NPR, and TODAY, and has worked with companies like Patagonia, Nike, and Google as well as a wide range of non-profits and other communities, sharing her "movement as nutrition" message. She is the host of the Move Your DNA podcast and lives in Washington State. More at nutritiousmovement.com and @nutritiousmovement.

How Your Mindset Changes Your Brain

5 Ways to Shift It For A Happier, Healthier, Wealthier Life

© 2024 Mary Morrissey

The power of mindset isn’t just in your thoughts––it actually changes your brain.

In search of the answer to answer that age-old question, “How can I have a better life?” your mindset is one of the most powerful tools you have.

But “mindset” can sometimes feel like an elusive, woo-woo term only internet “self-help gurus” seem to understand.

You may have even wondered if mindset is actually as impactful as often claimed!

This article will help you understand the real impact of mindset on your life and your biology––and how to enhance your mindset for well-being and success.

Understanding how your brain works in connection with your mindset, and visa-versa, will enable you to harness the power of mindset to actually change your life.

Plus, scroll to the end for a list of my favorite practical exercises and mantras to shift your mindset, starting now.

It’s easier than you think!

What is Mindset?

Your “mindset” is the lens through which you view yourself and the world around you. This lens is the tool your brain uses to simplify all of your life experiences into digestible pieces of information. The brain then uses those bite-sized chunks to set expectations, interpret new experiences, and make decisions.

You’ve probably heard of “fixed” and “growth” mindsets, one of the ways we understand and classify mindset among people. Stanford psychologist, Carol Dweck, Ph.D., coined these terms to describe the two basic belief systems that inform the way most people see themselves and the world.

In her book, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, Dweck writes:

“For twenty years, my research has shown that the view you adopt for yourself profoundly affects the way you lead your life. It can determine whether you become the person you want to be and whether you accomplish the things you value.”

According to Dweck, people with a fixed mindset believe their basic qualities, like intelligence or talent, are finite resources. They assume that they possess a certain set of skills from birth and they live their lives accordingly.

People with a growth mindset, on the other hand, believe that they can learn and improve through dedication and hard work. They approach life as if anything is possible with enough time, hard work, education, and training.

A person with a fixed mindset believes they cannot avoid failure, as it reflects their inherent abilities. But with a growth mindset, failure is an opportunity to learn, grow, and improve.

This worldview helps those who have adopted a growth mindset develop a resilience that is essential for great accomplishment!

Growth Mindset and the Brain

Research shows that those who develop a growth mindset achieve more and experience greater levels of success. More recently, it has also demonstrated that our mindset actually impacts the structure of our brains.

The brain is constantly creating and destroying neural connections. Our neural pathways represent the thought and behavior patterns our brain uses to make decisions and take action. Put simply, our brains strengthen the pathways we use and shrink (and eventually replace) the ones we don’t.

The ability of our brains to change throughout our lives is called “neuroplasticity.” In other words, our brains are able to undergo ongoing reorganization with learning and adaptation.

“The good news is mindsets are highly changeable, and if you are willing to learn the technology of changing your mindset and defeating your distorted thoughts, you can have significantly more happiness.” –Dr. Jacob Towery, Stanford University, Department of Psychiatry

As for the brain and growth mindset, these revelations mean two important things for you and me:

- First, neuroplasticity is biological evidence that developing a growth mindset is possible. This is true even for those who may be struggling with a fixed mindset right now.

- Second, a growth mindset isn’t just possible, our brains were actually designed to grow and change. Encouraging a growth mindset is in line with how your body and brain were intended to work.

How a Growth Mindset Changes the Brain

While researchers have typically measured mindset through outward behaviors, adopting a growth mindset has real, neurological impacts.

- Neuroplasticity: I’ve already shown you how neuroplasticity makes adopting a growth mindset possible. But, it’s also important to note that the more you practice a growth mindset, the more easily your brain is able to change. This flexibility allows for learning, growth, and even greater levels of success throughout life.

- Increased Connectivity: A growth mindset may lead to more connectivity between neurons in different regions of the brain. This enhanced inter-brain communication can improve cognitive function, creativity, and problem-solving abilities.

- Stress Response: Individuals with a growth mindset tend to have lower stress responses. This reduces the production of stress hormones, which can negatively affect neural structures and impair cognitive function.

- Enhanced Learning & Memory: Research suggests that a growth mindset improves the ability to learn. This involves increased activity in areas associated with learning and memory, such as the hippocampus.

- Resilience: Adopting a growth mindset can contribute to greater resilience in the face of challenges. This resilience influences the release of neurotransmitters associated with positive emotions, potentially leading to a more positive overall brain environment.

- Motivation and Reward Pathways: A growth mindset activates neural pathways associated with motivation and reward. This helps create a cycle of setting goals, taking on challenges, and experiencing the reward of progress. This same cycle, in turn, reinforces the growth mindset.

Fostering a growth mindset requires you to uncover and transform the beliefs that are no longer serving you––the limiting beliefs that are keeping you from reaching your full potential.

But, how can you identify your limiting beliefs?

For starters, try this:

5 Step Limiting Beliefs Exercise

Step One: Get out a piece of paper and a pen or pencil. Divide the paper in half, vertically, so that you have two columns to work with.

Step Two: Start by identifying an area or areas of your life you would love to transform. Then, in the left-hand column, write down a single statement that you feel accurately represents each struggle. For example:

- I can’t lose weight

- I’ll never be successful

- All of my relationships are difficult

- I can’t make enough money

Step Three: Then, add “because” to the end of each of the statements you wrote in the left-hand column. For example:

- I can’t lose weight because…

- I’ll never be successful because…

- All of my relationships are difficult because…

- I can’t make enough money because…

Step Four: Now, focusing on one statement at a time, set a time for 60 seconds. In the right-hand column, write down as many endings that you can think of to finish the problem statement.

The key is to work quickly and don’t overthink or second-guess what comes to mind. Treat this like a brainstorming session. For example:

I’ll never be successful because…

– I’m not smart enough

– I don’t have a graduate degree

– I don’t have enough consistency or follow-through

– People like me aren’t ever truly successful

– People won’t like me

Repeat this process for each of the problem statements you wrote in the left-hand column.

Step Five: Read through the list of fill-in-the-blank endings you’ve written in the right-hand column.

Highlight or underline those that feel the most true, bring up the most emotion, or trigger specific memories and past events. These statements are a great place to start gathering information as you challenge the limiting beliefs that may be making up your mindset.

Explore your responses further by considering where you may have learned or adopted these limiting beliefs (chances are, for example, you weren’t born believing something like “I’m not smart enough”).

Then, using all of the information you’ve gathered, identify a positive belief you can practice that is more true (even if you don’t fully believe it yet!).

Limiting Beliefs Exercise Example

Limiting belief: I’ll never be successful because I’m not smart enough.

Past memory: I may have learned this in second grade when I was struggling with multiplication tables. My teacher called on me to recite that week’s tables, and I couldn’t remember them. The class laughed at me.

New belief: Even though I decided back then that I wasn’t smart enough, the truth is I was smart enough to learn everything I needed to in 2nd grade. Just like multiplication, I can learn other new things now, including the things I need to be successful.

One of my favorite statements to use in this exercise is: That was then, this is now.

It works as a helpful reminder that we can validate the part of us that believed we needed our old beliefs to be safe and, at the same time, we are able to choose something different now.

After all, for most of us, it isn’t hard to see that we actually are much different than the younger versions of ourselves who helped form some of our most foundational beliefs.

We wouldn’t let a second grader make our most important life decisions, and for good reason! Our inner second grader is no exception!

This 5 Step Limiting Belief Exercise is the perfect place to start fostering a growth mindset.

And if you want to accelerate your progress even further, here are some additional tools to use.

5 practices to master your mindset

1. Learn to recognize your inner critic

Your inner critic is a reflection of your limiting beliefs and fuels your existing mindset. Most people aren’t aware of when their inner critic speaks up, but you can learn to recognize this voice for what it is.

Challenge yourself to be critical of your inner critic! Whenever you find yourself engaging in negative self-talk, get into the habit of scrutinizing the validity of what your inner critic is telling you. Ask yourself:

- Who does this voice sound like or remind me of?

- Do I have any objective, tangible evidence that what this voice is saying is true right now?

- Is there a part of me that believes this voice because of something that happened in the past?

- What part of me is benefitting from this voice? Is it keeping me safe? Is there another way I can help meet that need for myself?

Remind yourself that your inner critic is, at its root, a safety strategy developed by your subconscious mind. It represents a part of you that desires safety…but that doesn’t make what it tells you true!

Acknowledge the part of you that believes it needs the safety that inner critic offers, and then choose a more true statement for yourself.

Rinse and repeat! New beliefs become easier to integrate with repetition.

Remember, you are not your thoughts!

2. Use daily positive affirmations.

Daily, positive affirmations are a great, on-going tool you can use to begin to unravel and reset your mindset and the limiting beliefs that may no longer be serving you.

You can choose any affirmations that feel most aligned for you right now. Affirmations are simply positive, present tense statements of confirmation, validity, and belief.

And they work! Researchers have found that affirmations can predict positive changes in behavior. In other words, people who use affirmations are more likely to successfully make changes leading to long term, positive life changes!

Your own affirmations are powerful tools that declare to your subconscious mind and the universe what you hold to be true and possible about yourself and the world.

3. Practice asking better questions.

Often, our limiting beliefs are most identifiable through our thoughts and emotions. But most people accept their thoughts and feelings without question!

As we practice approaching our mindset with more intention, questions can be a powerful tool to help shift our beliefs and mental attitudes.

Learning to ask yourself the right questions is an opportunity to be your own life coach- you can respond to your own limiting thoughts and negative emotions with powerful, thought-provoking questions, just like a coach would with a client.

For instance:

Thought: “I always mess up. Why am I so stupid?”

Question: “What if messing up is just a sign I’m trying? What can I learn from this attempt to make next time different?”

Thought: “I can’t do this. I’ll never succeed.”

Question: “What can I do with what I have right now?

Thought: “Who am I to ask for a raise? They won’t recognize all the work I do anyway.”

Question: “What if asking for a raise is an experiment? No matter what the answer is, is it possible I could use that information to decide how to move forward?”

4. Practice visualization.

Visualization is a powerful tool used by some of the most successful people in the world to inspire success and motivate themselves to take meaningful action.

Visualization is also a tool that can help you master your mindset.

Spend time imagining the life you want to create like you’re writing a script for a movie in which you’re the main character.

Not only will this help you get clear on what you want and where you’re headed, but it will also help acclimate your mind to your vision for something bigger and better in your life. The part of you that might still be afraid of the unknown and relying on a limited mindset to keep you small and stuck will feel less triggered as you begin to take action in the direction of your vision!

Plus, spending time creating a clear image of the life you want to create has been proven to help people achieve the goals that they’ve set. A win-win!

5. Do it scared.

Sometimes, the best way to help yourself grow out of a sticky mindset is to start from the bottom and commit to taking small actions that might not align with the way you usually do things.

Imagine yourself 1 year from today. You’re living the life in which everything worked out just as you dreamed it would.

Then, ask yourself:

- In my current situation, what would that future version of me do?

- How would that future version of me react or respond to my current situation?

- What actions or decisions would that future version of me make right now?

The answers to those questions can help you begin to take small steps that can have a positive impact on your mindset while also helping you to move in the direction of your dreams!

Final Thoughts

Rewiring your mind for an expansive growth mindset doesn’t happen overnight, but it’s the single best investment you can make in your happiness.

As you embark upon the journey, here are some of the mantras that I remind myself of and repeat aloud to affirm the power of a growth mindset.

You are welcome to use these or build upon them to create your own!

- "Your mindset is the most powerful tool you possess. Use it wisely."

- “Every challenging situation you or I may ever face has a silver lining attached to it, even if we can’t see it right away.”

- “When you change your mindset and the way you think about things, you will connect with all of the potential inside of you.”

- “Keep a corner of your mind open to the possibility that there is so much more for you and in you than you have ever known.”

- “Be mindful of your words, as they are living energy.”

- “You are more powerful and contain far more potential than any circumstance, situation, or condition.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mary Morrissey is the founder of Brave Thinking Institute. Widely known as the world's leading authority on the invisible side of success, Mary is the author of three bestselling books: No Less Than Greatness, Building Your Field of Dreams (which became a PBS special) and Brave Thinking: The Art & Science of Building a Life You Love. She's worked closely with world leaders including The Dalai Lama and Nelson Mandela and addressed the United Nations three different times. She's also built three highly successful multi-million-dollar businesses from the ground up.

Over the last 40+ years, she's helped tens of thousands of people from all over the world find true happiness.

At the core of Mary's work is Brave Thinking: which she defines as living from a vision for a life you love, instead of letting circumstances and conditions dictate what's possible.

Interfaith at the Bedside

Reflections of a Hospice Chaplain

© 2021 Barbara Becker

Heartwood: The Art of Living with the End in Mind in Mind by Barbara Becker. Used with the permission of Flatiron Books. Copyright © 2021 by Barbara Becker.

MRS. B, ROOM #724

The nurse at the front desk on the hospice floor had tipped me off that Mrs. B in room #724 could use a visit. She was in the final stages of congestive heart failure and didn’t have much time.

It was my first week on the job as a hospice volunteer, and I was consumed by getting to know the ropes. I was relieved that the unit, with its white carpeting and abstract paintings on the walls, looked more like a tasteful boutique hotel than a place where people went to die. My biggest fear was entering the room of a new patient and figuring out how to begin. Koshin, the Zen monk who served as my mentor, had advised me to simply say hello and find a chair. He always made things seem easy.

I knocked on Mrs. B’s door and entered. Just beyond the large window near her bed, the East River shimmered in the early-morning light. Mrs. B was tenderly petting a stuffed animal, a bright-green tree frog that was resting on her legs, facing her with its large, unblinking eyes.

“Come in,” she said. I noticed a rosary with blue beads and a silver cross in her fragile, aged hand.

“I’m Barbara, and I’m a volunteer here. Would you like a visitor?”

“Please sit down,” she said, indicating the upholstered guest chair beside her bed. I was glad to be asked.

We chatted about the framed photos on her windowsill—her two daughters and many grandchildren. Recently there were great-grandchildren. She grew silent.

“What were you thinking about when I walked in?” I asked, sensing that she was waiting to see if I would accompany her to the truest place this conversation could go. It didn’t take long.

“I know I’m not going to be around for much longer. Myself, I’m at peace with that. But Thanksgiving is a few months away, and Christmas right after that. I don’t want to leave my family during the holidays.”

I fumbled my way along with Mrs. B, acknowledging her sadness. I tried my best to leave the door open for the possibility that her daughters and their families would pick up where she had left off, carrying on the family’s rituals, remembering her, and cherishing one another. Sometimes in loss, we remember most to love, I said.

Now a tear was following the path of a wrinkle etched into her face. I handed her a tissue from the bedside table, which she took with a shaking hand. “My grandson in New Mexico called yesterday. He’s sad because he’s not going to make it to see me before I pass, what with his job and all.”

“Have you thought about writing him a letter?” I asked, seeing an opportunity to help them both.

She seemed to brighten a little. “I can’t write anymore, but I can dictate if someone could write for me,” she said, adjusting the clear oxygen tube that fit into her nose.

I walked with purpose down the hall to the volunteer office and after some searching found a stack of pretty pink stationery with a scalloped edge.

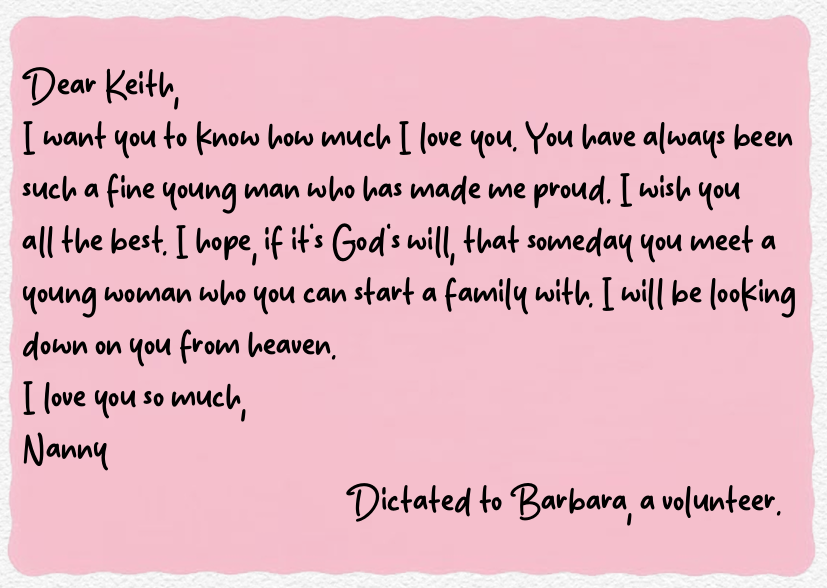

That morning, Mrs. B dictated a letter to me for her grandson Keith. It wasn’t long or poetic, but I knew she meant every word.

After that, she asked me to write more letters—for her daughters, her grandchildren, and even her great-grandchildren. She also had me write to her church community and her bridge club. All of these people in her life’s wide net, I thought. We should all be so lucky.

When I was done, she asked me to put the letters in her small overnight bag so that her family would find them easily after she was gone.

I wished I had some poetry or prayers memorized to recite at a time like this. But I could only remember the first line of a comforting Bible passage that had been made into a song. So I recited it:

To every thing there is a season,

and a time to every purpose under heaven.

“Thank you,” she said, leaning her head back onto her pillow. “Do you have another?”

I recalled one that might fit. “Do you know the Serenity Prayer?” I asked.

“Oh yes,” she said, smiling and seeming small, as if she were disappearing into her fluffy bathrobe.

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change—she was mouthing it along with me—courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.

“I asked God to send me an angel this morning,” she said. “Now I know it was you.”

I asked Mrs. B if I could give her a kiss goodbye. Right there in room #724, I loved this woman called Nanny as if she were my own. I leaned over and brushed my lips against her warm forehead.

I have certainly never envisioned myself with wings of any sort. We are, all of us, imperfect beings. But in that moment, I realized that we all carry a humble spark of connection and love, there for the taking and there for the giving, that simple gift of showing up.

MR. R, ROOM #734

“It would be helpful to us if you could spend some time with Mr. R in 734,” the social worker on the hospice floor said as soon as I walked into the volunteer office one morning. There had been two deaths the night before, and everyone was extremely busy talking to the families, filling out paperwork, and preparing the rooms for those who would come next.

“Sure,” I said, hanging up my coat. “What can you tell me about him?”

“He’s a Muslim man, in his seventies, and completely alone.”

I put on my volunteer badge, pulled my hair back from my face, and set off down the hall, trying to bring to mind the little I knew about Islam.

I recalled a day a few months earlier, when I had been overcome by nostalgia on the anniversary of my childhood friend Marisa’s death. I had thought about her all that day and about the time I had spent living life with the end in mind. I’d remembered the bucket-list trip to Turkey that Dave and I took with the boys, ages six and nine. The night we had arrived in Istanbul, I led my jet-lagged family to a darkened hall to see the whirling dervishes of the poet Rumi’s order of Sufism, the mystical dimension of Islam. One boy on either side of me, I felt their sleepy bodies grow heavy as they leaned against my shoulders. Dave had looked over and smiled softly. In the blur of the dervishes’ long, spinning skirts and alluring music, I had felt that all was right with the world.

The memory of being completely absorbed by the dervishes’ embodied act of devotion had made me wonder if there was a Sufi community in New York City. I was surprised to find one within walking distance of our apartment, not far from where I had stood on 9/11 with our son Evan in a stroller, watching as the twin towers were engulfed in flames.

I wasn’t thinking at all about future hospice patients when I walked through the front door of the three-story Sufi center in Tribeca those few months before. I entered a large open room, where plush sheepskin rugs were placed in a circle on a floor covered with thick red Persian carpets. Two dimly lit chandeliers hung from the ceiling, and green banners with golden Arabic calligraphy decorated the white-painted brick walls.

A woman with short hair and round glasses put her hand to her heart in greeting and introduced herself as Zhati. “Come sit by me, and I’ll explain everything,” she said graciously, pointing to a seat on a wooden bench, just outside the sheepskin circle.

A few dervishes leaned over to say hello. There was a couple—newlyweds from Pakistan—a woman originally from Istanbul, and a man from Harlem.

The room grew quiet as an elegant woman of about seventy entered and sat down. Zhati told me that she was Shaykha Fariha, the first Western woman to be named as the spiritual guide of this Sufi order.

“We don’t worry too much about formal religion here,” Shaykha Fariha said, addressing the gathering. “This Sufi path is the mystical path of love. Of the divine union between the Lover and the Beloved, which is our true essence. And the zikr is our practice of remembering God.”

A woman with a white prayer cap circulated through the group, tipping a bronze genie-like bottle into each of our outstretched hands. I took a cue from those who went before, holding my hands to my nose to smell the rose water, then rubbing it into my palms and passing them over my hair and face.

The group began chanting La ilaha illallah, swaying their heads rhythmically from right shoulder to left. I followed along, as the repetition became faster, then shorter. Illallah, illallah—a sound that seemed like a human heart as heard from within the body. I began to feel slightly hypnotized, slightly euphoric, as the words were repeated perhaps one hundred times.

Zhati leaned over and explained La ilaha illallah—part of the universal declaration of faith repeated by all Muslims the world over—as I imagined a mystic might: “Other than God, there is nothing. Beyond all of the worldly deities our egos love to worship—ambition, power, wealth, social status, appearance—one reality exists. Die to the old outmoded way of being that no longer serves the fullness of who we truly are.”

Zhati adjusted the long string of prayer beads around her neck and looked at me intently. “Die before you die. This is how we come to life.”

After a while, the group rose and formed two concentric circles. Holding hands, we moved step over step to the left. A woman with a large frame drum and a man with a string instrument called a setar began playing, while another man entered the center of the circle and cupped a hand behind one ear. His voice rang out melodically in Arabic.

The group now seemed like a single beautiful organism, rippling along.

With Shaykha Fariha leading, everyone dropped hands and began to turn individually, slowly to the left, in the direction of the heart. Two women in flowing white skirts and a man with a long vest whirled faster and faster. I moved my feet out of their way, wondering if they ever got dizzy.

The dervishes spun for nearly fifteen minutes, without pausing until, with a sudden clap of her hands, Shaykha Fariha brought their movement to an end. The whirlers crossed arms over chest and bowed their heads. They reminded me of figure skaters who manage to end a performance in a gracefully steady pose after having spun so fast their pirouetting bodies seemed in danger of turning permanently rubberized.

The zikr ended after midnight. I was exhausted yet feeling completely alive. The smell of rose water, the light streaming from the chandeliers, the sounds of voices and music, and the meditative movement had captivated me, and I knew I would come back someday.

But what my experience that night would have to do with being called to the bedside of a dying Muslim man three months later, I would never have been able to say.

Mr. R was lying in a fetal position, facing the door. Even though he was covered with a sheet, I could tell that his frame was tall and skeletal. And he was shaking uncontrollably.

I dragged the heavy beige upholstered chair closer to the side of his bed and sat on its arm.

“Mr. R, my name is Barbara.” No response. “If it’s okay with you, I thought I would just sit here with you for a while.”

His shaking was unnerving. I could almost feel my own brain rattling in my skull as I watched his body convulse. I leaned in closer to his bed and impulsively began humming, every bit as much to soothe myself as to soothe him.

When my own song was finished, I heard another verse from my memory. Faintly at first, La ilaha illallah-the Arabic incantation the Sufis had repeated over and over during their gathering—formed in my ears. They were the same words I had heart echo through the alleys of Dhaka while I was working in Bangladesh, and everywhere we had traveled in Turkey, as part of the prayer called from minarets five times each day.

I leaned closer to Mr. R and from the depths of my heart whispered the sacred words: La ilaha illallah. Nothing, only this.

After several rounds of repetition, I began to wonder about him. What was the cause of his shaking? Where was his family? Did it matter, when no one else was available, that I wasn’t Muslim? The beauty of the ancient phrase drowned my questions before I could formulate my guesses. None of the answers seemed worthy of this moment. La ilaha illallah.

Eventually I noticed that Mr. R’s shaking had stopped. When I moved away

from the bed, his body began to convulse wildly again, so I continued with the rhythm. La ilaha illallah. La ilaha illallah. I hadn’t expected the chant to affect me as much as it did. He stopped being the unwell person and I the well one. The one in need of help and the helper. He a man, I a woman. He older, I younger. What could possibly be the use of divisions like that?

An hour and a half must have passed. I had to leave to go to work. His eyes were still closed, and he was still not responsive. But I told him how sorry I was to have to leave anyhow. As his shaking began again, I backed out of the room very slowly, not wanting to turn away from him for even a moment. It was wrenching to leave him this way.

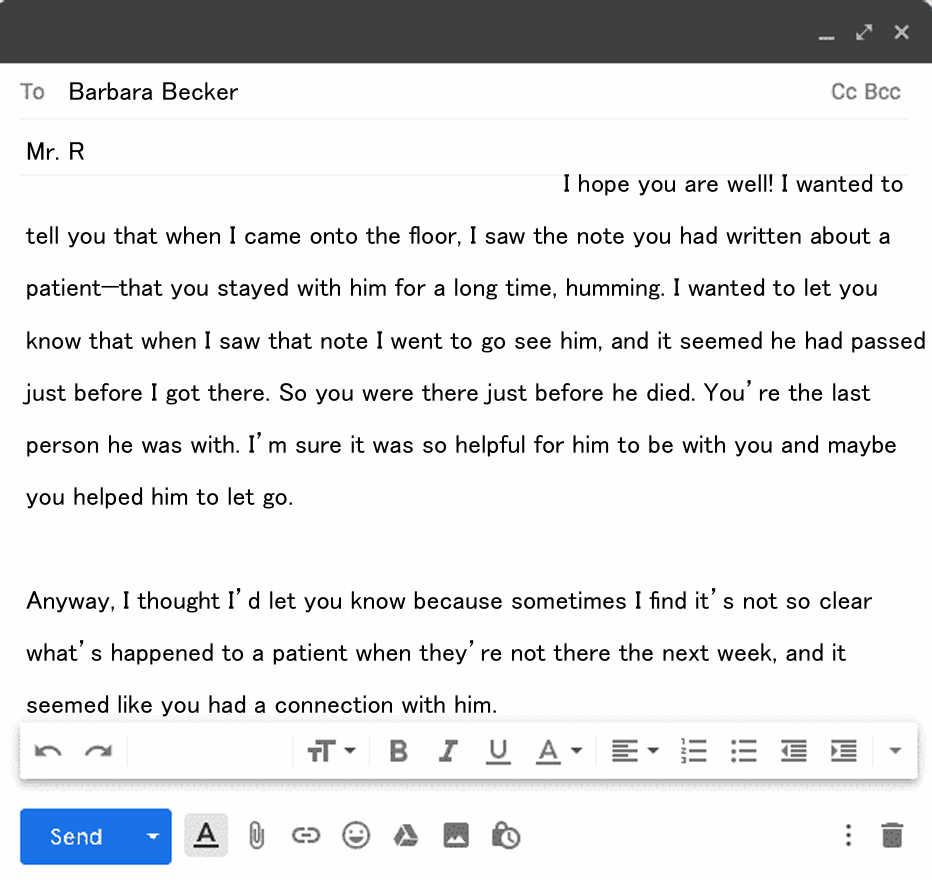

When I switched on my computer at my desk an hour later, I was surprised to see an email from the volunteer whose shift followed mine:

I leaned back in my chair, overwhelmed with emotion. My connection with Mr. R had been so short, but the length of our meeting had hardly mattered. There seemed to be a place beyond time, and we had met there with offerings to each other. His had been a tremendous gift of illuminating our interconnectedness, and all I wanted to do was to thank him for allowing me to join him for a while. I opened the window by my desk, turned my face into the cool breeze, and breathed his name.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Barbara Becker is a best-selling author and international human rights advocate. Her Gold Nautilus Award-winning memoir, Heartwood: The Art of Living with the End in Mind was named a “Book that will Change Your Life” by Katie Couric Media. She has worked with the United Nations, Human Rights First, the Ms. Foundation for Women, and the Grameen Bank of Bangladesh, and has participated in a delegation of Zen Peacemakers and Lakota elders in the sacred Black Hills of South Dakota. She is also an ordained interfaith minister who bridges the sacred and the secular, and has sat with hundreds of people at the end of their lives. Barbara lives in New York City with her husband David. More at barbarabecker.com

Skillful Means: Having an Inner Smile

Your Skillful Means, sponsored by the Wellspring Institute, is designed to be a comprehensive resource for people interested in personal growth, overcoming inner obstacles, being helpful to others, and expanding consciousness. It includes instructions in everything from common psychological tools for dealing with negative self talk, to physical exercises for opening the body and clearing the mind, to meditation techniques for clarifying inner experience and connecting to deeper aspects of awareness, and much more.

Having an Inner Smile

PURPOSE/EFFECTS

Sometimes we can get in our own way by striving too hard or taking life too seriously. Smiling and lightening up can be beneficial for both physical and mental health. Having an inner smile means we’re greeting our experience with more kindness and openness. As Thich Nhat Hahn says, “You need to smile to your sorrow because you are more than your sorrow.” Holding an inner smile also reminds us to keep a sense of humor and avoid being too hard on ourselves.

METHOD

Summary

You can maintain an inner smile in everyday life as well as during formal practices such as yoga, prayer, or meditation; gently smile to yourself, with kindness, appreciation, and a sense of perspective.

Long Version

- Gently smile to yourself.

- The smile is not so much a physical gesture, but is more of a gentle, internal smile.

- Let this smile remind you not to strive too hard or criticize yourself. Also, let it make your thoughts, words, and deeds more gentle and accepting.

- Be mindful of what it’s like to maintain this gentle smile, and notice if any reactions arise.

- If you notice that you have become caught up in striving or struggling, remember to smile. See if you can find any humor in your thoughts or experience.

- Also, if you notice strong thoughts, emotions, or sensations arise that are particularly challenging, see if you can meet them with a smile. You are not denying them or resisting them. You are just opening to the possibility that these experiences are not your true identity, and you are much more than them.

- Practice “smiling” at difficult situations or relationships to honor and acknowledge them with friendliness. Notice what happens when you do this.

HISTORY

Holding an inner smile is taught in Daoism, Mahayana Buddhism, and also by Buddhist meditation teacher Thich Nhat Hanh.

NOTES

Please note that by smiling at your experience you are not trying to deny or diminish it, you are simply meeting what is present with friendliness.

SEE ALSO

EXTERNAL LINKS

A guided meditation by Thich Nhat Hahn incorporating smiling