News and Tools for

Happiness, Love, and Wisdom

volume 14.6 • December 2020

In This Issue

Good morning, I love you

© 2020 Shauna Shapiro PhD

And did you get what you wanted from this life, even so? I did. And what did you want? To call myself beloved, to feel myself beloved on the earth. --Late Fragment by Raymond Carver [written while dying of cancer]

Eleven years ago, I went through a painful divorce. I was hurt and alone. The damage was irreparable and the choice to leave was inevitable, but I still felt like a failure. No one in my family had ever divorced. My grandparents had been married for seventy years; my parents forty. All my aunts and uncles had thriving marriages, my sister was (and still is) happily married to her college sweetheart, and my brother had just gotten engaged to the woman of his dreams. Marriage in my family was sacrosanct. The prospect of upending my life was terrifying. But that was nothing compared to my fear of how the divorce would affect our three-year-old son Jackson.

Despite my fears, I packed up everything I could fit into my tiny car, buckled Jackson into his car seat, and drove to Marin County, California where my grandparents lived. I needed to be close to family. Reflecting on my journey, I've learned the importance of understanding things not to say to a child of divorce, ensuring that they feel loved and supported through every transition. Navigating the complexities of Maryland child support has also been a crucial part of this process. Ensuring proper financial support helps maintain stability and meets the child's needs during challenging times. Contact this fathers rights lawyer if you need an attorney that can help protect your rights during the divorce proceedings. You may also consult this Dutchess County divorce attorney for legal advice. Get started on couples therapy here.

How to terminate child support arrears? Terminating child support arrears typically involves fulfilling the outstanding payment obligations or negotiating with the court for a modification or forgiveness based on changed circumstances or legal grounds.

And Nana and Grandpa were my home. Once we’d crossed the Golden Gate Bridge and exited at Sausalito, we passed a small apartment building with a For Rent sign out front. I could tell just from the outside that it was out of my price range, but they were holding an open house that day, so I figured I’d take a quick look around.

The owner, a large man with striking features and ebony skin, answered the door. He warmly greeted us: “I’m Ishmael”—and then, observing my face more closely, and my car out front with all my belongings visibly packed into it: “Looks like you’re having a tough day.”

Greetings

The Wise Brain Bulletin offers skillful means from brain science and contemplative practice – to nurture your brain for the benefit of yourself and everyone you touch.

The Bulletin is offered freely, and you are welcome to share it with others. Past issues are posted at http://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin. Michelle Keane edits the Bulletin, and it’s laid out by the design team at Content Strategy Online. To subscribe, go to http://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin.

I told him I’d just left my husband and was looking for a place to live. And then, much to my surprise, I burst into tears. His reaction I will never forget. “Young lady, sounds like you need a break.” He had no reason to help me, but he did. We worked out the logistics and he introduced his nephew, who would be my landlord. As I left, he gently said, “Remember this when you can help someone else get back on their feet.” I never saw Ishmael again, but I will never forget his kindness. A week later, a soft beam of sunshine woke me. I blinked my eyes open, taking in the bare walls surrounding me. I was lying on the floor of what was once a barn but had been transformed into a stylish barndominium, with Jackson snuggled in my arms. We had no furniture yet, so I’d zipped together two sleeping bags to make a little nest for us. This transformation from barn to cozy home was something my cousin, who works at a real estate company, had helped us with. His knowledge of such unique conversions made the transition smoother than I had ever imagined. As the sun filled the room, brightening the exposed beams and open space around us, I was filled with gratitude for the guidance we'd received, making this barndominium our own. It was the warmth of the sun and the love for Jackson that gave me the strength to embrace this new chapter, one step at a time. Yet, over the next several weeks, with each step forward, I seemed to take two backwards. I was adjusting to life as a single parent, juggling child care, and commuting three hours roundtrip to teach at the University. My life felt overwhelming. This was not how I imagined things would be. I felt exhausted and hopeless. I was trying so hard, but each morning I’d wake with the same aching pit of fear and shame in my gut—my monkey mind swinging between ruminations about the past: “If only I had . . .” and fears about the future: “How am I going to handle it when _______ happens?” I couldn’t seem to shake the self-judgment and sense that I had failed. There was no space for self-compassion. No space for self-kindness. No space for joy. Friends, family, and colleagues all saw the pain I was in. Many offered support and ideas. One of my meditation teachers suggested I begin each day by saying, “I love you, Shauna.” I immediately balked. Yuck! It felt so contrived, so inauthentic. She noticed my hesitation and suggested, “How about simply saying ‘Good morning, Shauna’?” Then, with a wink, she added, “Try putting your hand on your heart when you say it. It will release oxytocin—which, as you know, is good for you.” She knew the science would win me over. The next morning, when I awoke, I resolutely put my hand on my heart, took a breath, and said, “Good morning, Shauna.” Much to my surprise, it felt kind of nice. Instead of the avalanche of shame and anxiety that usually greeted me upon awakening, I felt a flash of kindness. I practiced saying “Good morning, Shauna” every day, and over the next few weeks I began to notice subtle changes—a bit less harshness, a bit more kindness. Little did I know that this small practice would lead to big changes.  One Sunday morning, I was out for a walk in our new neighborhood and passed an old basketball gym. I was surprised to hear loud music and laughter pouring out onto the street. What could be making so much noise at 8:00am on a Sunday?! Curious, I peeked through the door and saw about 200 people of all ages, shapes, sizes, and colors . . . dancing. Some were clearly professional dancers—others clearly were not. But all had one thing in common: a look of pure joy on their faces. As a young girl, I had danced with the Pacific Ballet conservatory and fallen in love with dance. I especially loved the performances, when somehow my mind quieted and the dance became a joyful expression of my soul. But after my back surgery, I stopped dancing. My body was no longer a safe place. It was filled with pain. It didn’t move the way I wanted it to—even simple movements like glancing over my shoulder or walking were awkward and disconnected. Dancing was out of the question.

One Sunday morning, I was out for a walk in our new neighborhood and passed an old basketball gym. I was surprised to hear loud music and laughter pouring out onto the street. What could be making so much noise at 8:00am on a Sunday?! Curious, I peeked through the door and saw about 200 people of all ages, shapes, sizes, and colors . . . dancing. Some were clearly professional dancers—others clearly were not. But all had one thing in common: a look of pure joy on their faces. As a young girl, I had danced with the Pacific Ballet conservatory and fallen in love with dance. I especially loved the performances, when somehow my mind quieted and the dance became a joyful expression of my soul. But after my back surgery, I stopped dancing. My body was no longer a safe place. It was filled with pain. It didn’t move the way I wanted it to—even simple movements like glancing over my shoulder or walking were awkward and disconnected. Dancing was out of the question.  Sixteen years post-surgery and just a few months after leaving my marriage, there I was, standing in the doorway watching all these people joyfully dancing. Seeing me peeking in like a hesitant schoolgirl, an older woman with shining silver hair motioned for me to join. I turned and fled. The next Sunday I found myself walking by the same old gym. The music played like the Pied Piper and again I peered in, longing to dance but afraid to join. Over the next couple of weeks, my Sunday walks past the gym became as much a ritual as my “Good morning, Shauna” practice. But I didn’t go in. I longed to dance, to feel that freedom I remembered and loved so well, yet I didn’t trust my body. I was terrified of trying to dance again—of feeling awkward and vulnerable in front of a bunch of strangers. Then one Sunday, I set my intention to walk through that gym door and dance, no matter what. I committed to practicing an attitude of kindness and curiosity no matter what happened and no matter how I felt. That morning when I got to the gym, I went in. I stood in a corner, alone, eyes closed, while the music and movement surged all around me. I tried to gently move my body, simply trying to feel it. I didn’t dance with anyone. I didn’t even look at anyone. But slowly, my body began to move.

Sixteen years post-surgery and just a few months after leaving my marriage, there I was, standing in the doorway watching all these people joyfully dancing. Seeing me peeking in like a hesitant schoolgirl, an older woman with shining silver hair motioned for me to join. I turned and fled. The next Sunday I found myself walking by the same old gym. The music played like the Pied Piper and again I peered in, longing to dance but afraid to join. Over the next couple of weeks, my Sunday walks past the gym became as much a ritual as my “Good morning, Shauna” practice. But I didn’t go in. I longed to dance, to feel that freedom I remembered and loved so well, yet I didn’t trust my body. I was terrified of trying to dance again—of feeling awkward and vulnerable in front of a bunch of strangers. Then one Sunday, I set my intention to walk through that gym door and dance, no matter what. I committed to practicing an attitude of kindness and curiosity no matter what happened and no matter how I felt. That morning when I got to the gym, I went in. I stood in a corner, alone, eyes closed, while the music and movement surged all around me. I tried to gently move my body, simply trying to feel it. I didn’t dance with anyone. I didn’t even look at anyone. But slowly, my body began to move.  I continued to go every Sunday morning, and one millimeter at a time, I began to re-inhabit my body. I began to feel parts that had been completely numb. And as my body began to wake up, I became aware of the emotions that had gotten locked inside—loss, grief, vulnerability, rage. As I danced, these emotions began to move through me. As I made space for them, they began to transform. Unexpectedly, a new emotion arose: compassion. I began to feel compassion for the young woman still inside, who had lived for so long in pain, feeling awkward and alone. Then one day, the tears came. First one, then two tears escaped my closed eyes, sliding down my cheeks. As I continued to dance, the river of tears released something, and my body began to spin—round and round, twirling, eyes closed. Whirling tears, snot, and sweat. No thoughts, no judgment. And then a lightness filled my being, a freedom in my body: Joy. As the music began to fade, my movements slowed, and I gently laid down on the floor. I felt at peace. I felt hope. “God circled this place on the map just for you,” wrote the fourteenth-century Persian poet Hafez. Maybe he was right. Maybe I was supposed to be here. My life wasn’t how I expected, and it certainly was far from perfect. But that was OK. I could begin again.

I continued to go every Sunday morning, and one millimeter at a time, I began to re-inhabit my body. I began to feel parts that had been completely numb. And as my body began to wake up, I became aware of the emotions that had gotten locked inside—loss, grief, vulnerability, rage. As I danced, these emotions began to move through me. As I made space for them, they began to transform. Unexpectedly, a new emotion arose: compassion. I began to feel compassion for the young woman still inside, who had lived for so long in pain, feeling awkward and alone. Then one day, the tears came. First one, then two tears escaped my closed eyes, sliding down my cheeks. As I continued to dance, the river of tears released something, and my body began to spin—round and round, twirling, eyes closed. Whirling tears, snot, and sweat. No thoughts, no judgment. And then a lightness filled my being, a freedom in my body: Joy. As the music began to fade, my movements slowed, and I gently laid down on the floor. I felt at peace. I felt hope. “God circled this place on the map just for you,” wrote the fourteenth-century Persian poet Hafez. Maybe he was right. Maybe I was supposed to be here. My life wasn’t how I expected, and it certainly was far from perfect. But that was OK. I could begin again.  One Sunday, I saw a man who danced as if his soul were choreographing every movement. I asked where he had learned to dance like that. He responded with one word: Esalen. When I got home I immediately Googled Esalen and learned it was the very same retreat center in Big Sur, California where my father had taught when I was a young girl. And, in yet another coincidence, they were holding a dance workshop the following month—during the week of my birthday. This would be my first birthday without my son, as he was going to be with his father at a long-scheduled family reunion in New York. I decided to go! Driving through the gates of Esalen, the first thing I saw was a magnificent garden with eight-foot sunflowers, rows of lettuces and dinosaur kale, and the lush fronds of a banana tree—a kaleidoscope of color. Even more extraordinary were the hot springs, on a rocky cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean. The next morning was my birthday. I woke just before dawn and headed straight for the hot springs. Cool mist from the ocean mingled with steam from the springs, blanketing the world around me. I eased into the steaming waters. The sky was starting to lighten, announcing dawn’s arrival. I put my hand on my heart, preparing to do my “Good morning, Shauna” practice. Something about the magic of the place, the enfolding arms of the water and the mist, evoked an image of my grandmother, and the next thing I knew, I was saying, “Good morning, I love you, Shauna. Happy Birthday.”

One Sunday, I saw a man who danced as if his soul were choreographing every movement. I asked where he had learned to dance like that. He responded with one word: Esalen. When I got home I immediately Googled Esalen and learned it was the very same retreat center in Big Sur, California where my father had taught when I was a young girl. And, in yet another coincidence, they were holding a dance workshop the following month—during the week of my birthday. This would be my first birthday without my son, as he was going to be with his father at a long-scheduled family reunion in New York. I decided to go! Driving through the gates of Esalen, the first thing I saw was a magnificent garden with eight-foot sunflowers, rows of lettuces and dinosaur kale, and the lush fronds of a banana tree—a kaleidoscope of color. Even more extraordinary were the hot springs, on a rocky cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean. The next morning was my birthday. I woke just before dawn and headed straight for the hot springs. Cool mist from the ocean mingled with steam from the springs, blanketing the world around me. I eased into the steaming waters. The sky was starting to lighten, announcing dawn’s arrival. I put my hand on my heart, preparing to do my “Good morning, Shauna” practice. Something about the magic of the place, the enfolding arms of the water and the mist, evoked an image of my grandmother, and the next thing I knew, I was saying, “Good morning, I love you, Shauna. Happy Birthday.”  The dam around my heart gave way and a flood of love poured in. I felt my grandmother’s love. I felt my mother’s love. I felt my own self-love. A sense of peace flowed through my body. I wish I could tell you that my life has been a bubble of self-compassion ever since, and that I’ve never again experienced shame or self-judgment. But of course that’s not true. What is true is that I continue to practice. Every morning, I put my hand on my heart and say, “Good morning, I love you, Shauna.” Some days I feel awkward, some days I feel lonely and raw, and some days I feel profound love. Whatever I feel, I keep practicing, and every morning, this pathway grows stronger. The Good Morning, I Love You practice continued to evolve and expand over the years. I began greeting the sunshine, the birds chirping in my backyard, the flowering jasmine outside my bedroom window. One morning, I even sent a “Good morning, I love you” to the garbage truck that woke me up! I began saying “Good morning, I love you” to Jackson even if he wasn’t there, which eased the ache when he was away at his father’s house. I began to say it to my dear friends and family; to people I was working with; to my students. Eventually I started sending this greeting out to the world. I even began sending a silent good morning, I love you to my ex-husband, whom I realized I’d been leaving out.

The dam around my heart gave way and a flood of love poured in. I felt my grandmother’s love. I felt my mother’s love. I felt my own self-love. A sense of peace flowed through my body. I wish I could tell you that my life has been a bubble of self-compassion ever since, and that I’ve never again experienced shame or self-judgment. But of course that’s not true. What is true is that I continue to practice. Every morning, I put my hand on my heart and say, “Good morning, I love you, Shauna.” Some days I feel awkward, some days I feel lonely and raw, and some days I feel profound love. Whatever I feel, I keep practicing, and every morning, this pathway grows stronger. The Good Morning, I Love You practice continued to evolve and expand over the years. I began greeting the sunshine, the birds chirping in my backyard, the flowering jasmine outside my bedroom window. One morning, I even sent a “Good morning, I love you” to the garbage truck that woke me up! I began saying “Good morning, I love you” to Jackson even if he wasn’t there, which eased the ache when he was away at his father’s house. I began to say it to my dear friends and family; to people I was working with; to my students. Eventually I started sending this greeting out to the world. I even began sending a silent good morning, I love you to my ex-husband, whom I realized I’d been leaving out.  Eventually, I began to teach this practice to my students and my clients, and finally shared it in a TEDx talk. Now well over two million people have learned the Good Morning, I Love You practice. I’ve been awed and inspired by the ripple effect of this practice, and how it has changed people’s lives. Thousands of people have shared their own Good Morning, I Love You stories with me. One 5-year-old boy sent me a video of his practice. He sat, eyes closed, his little hand on his heart. He took a deep breath and bellowed, “Good morning, I love you, Nathan!” Then he peeked his eyes open and shyly whispered, “Good morning, I love YOU, too.” Another Good Morning, I Love You story began when I received a note via Instagram from a young mother named Kristen. Her three-year-old son was in the hospital recovering from brain surgery. She wrote that she’d seen my TEDx talk and had been practicing with her son every day. I responded to her message and we realized she lived near Phoenix, where I would be teaching a workshop called Messy Motherhood. I invited her to attend. As Kristen, 400 other mothers, and I put our hands on our hearts and practiced Good Morning, I Love You, the sense of connection and compassion were palpable. We expanded our “Good morning, I love you” to include all children facing illness, and to all of their parents. We continued to expand our circle of compassion in all directions, to all beings. All of us were crying by the end of the practice. Tears of love, tears of hope. I received a letter from Kristen while I was writing this book. Her son, now four, is healthy and thriving; all brain scans are clear. She wrote, “(these practices) helped me get through one of the most difficult chapters of my life, and come out of it stronger and more connected to myself than I have ever been.” Another story came from Azar, a recently widowed seventy-year-old woman originally from Iran. We began working together to help with the loss of her husband. At that time, she was terrified of the world, having never navigated it alone. She also felt lonely and without love in her life. As she began to practice Good Morning I Love You, she began to slowly transform. Azar began to engage in dance classes and poetry groups. A year later, she traveled alone for the first time in her life—to attend one of my mindfulness retreats. At the retreat, she shared with the group how this practice had changed her life, and how she says, “Good morning, I love you” to herself and to her late husband each day. She shared that it opened her up to feeling love and joy again. Three years later, Azar was diagnosed with breast cancer. I have never seen anyone fight harder for her life. She won. Azar now volunteers teaching mindfulness to support groups for women with cancer. I’ve witnessed how this simple practice has catalyzed change in so many lives, I’ve come to see it an intimate practice that spirals out into the world and back in again to our own heart. It is a simple yet powerful practice that has changed lives. I know it can change yours.

Eventually, I began to teach this practice to my students and my clients, and finally shared it in a TEDx talk. Now well over two million people have learned the Good Morning, I Love You practice. I’ve been awed and inspired by the ripple effect of this practice, and how it has changed people’s lives. Thousands of people have shared their own Good Morning, I Love You stories with me. One 5-year-old boy sent me a video of his practice. He sat, eyes closed, his little hand on his heart. He took a deep breath and bellowed, “Good morning, I love you, Nathan!” Then he peeked his eyes open and shyly whispered, “Good morning, I love YOU, too.” Another Good Morning, I Love You story began when I received a note via Instagram from a young mother named Kristen. Her three-year-old son was in the hospital recovering from brain surgery. She wrote that she’d seen my TEDx talk and had been practicing with her son every day. I responded to her message and we realized she lived near Phoenix, where I would be teaching a workshop called Messy Motherhood. I invited her to attend. As Kristen, 400 other mothers, and I put our hands on our hearts and practiced Good Morning, I Love You, the sense of connection and compassion were palpable. We expanded our “Good morning, I love you” to include all children facing illness, and to all of their parents. We continued to expand our circle of compassion in all directions, to all beings. All of us were crying by the end of the practice. Tears of love, tears of hope. I received a letter from Kristen while I was writing this book. Her son, now four, is healthy and thriving; all brain scans are clear. She wrote, “(these practices) helped me get through one of the most difficult chapters of my life, and come out of it stronger and more connected to myself than I have ever been.” Another story came from Azar, a recently widowed seventy-year-old woman originally from Iran. We began working together to help with the loss of her husband. At that time, she was terrified of the world, having never navigated it alone. She also felt lonely and without love in her life. As she began to practice Good Morning I Love You, she began to slowly transform. Azar began to engage in dance classes and poetry groups. A year later, she traveled alone for the first time in her life—to attend one of my mindfulness retreats. At the retreat, she shared with the group how this practice had changed her life, and how she says, “Good morning, I love you” to herself and to her late husband each day. She shared that it opened her up to feeling love and joy again. Three years later, Azar was diagnosed with breast cancer. I have never seen anyone fight harder for her life. She won. Azar now volunteers teaching mindfulness to support groups for women with cancer. I’ve witnessed how this simple practice has catalyzed change in so many lives, I’ve come to see it an intimate practice that spirals out into the world and back in again to our own heart. It is a simple yet powerful practice that has changed lives. I know it can change yours.  Good Morning, I Love You: The Full Practice I always do the Good Morning, I Love You practice first thing when I wake up. While lying in bed, I place my hand on my heart and take a moment to simply feel the connection; to receive this tender gesture of self-care. Please continue with me:

Good Morning, I Love You: The Full Practice I always do the Good Morning, I Love You practice first thing when I wake up. While lying in bed, I place my hand on my heart and take a moment to simply feel the connection; to receive this tender gesture of self-care. Please continue with me:

- Place your hand on your heart. Focus on your palm. Feel your heart pulsing through your chest.

- Feel how your heart is taking care of you, sending oxygen and nutrients to the trillions of cells in your body. The heart knows exactly how to care for you—you don’t have to control it or even think about it. Simply receive the nourishment.

- When you’re ready, take a breath, and say, “Good morning, [your name].” or “Good morning, I love you, [your name].”

- Notice how this makes you feel. See if you can bring kindness and curiosity to however you are feeling. There is no right or wrong way to feel.

- Trust that you are planting the seeds of presence and compassion for yourself and that these seeds will grow and strengthen the neural substrates of self-love.

- Send these seeds of blessing out into the world, offering the phrase “Good Morning, I Love You” to anyone who comes to mind.

- Recognize that we are never just practicing for ourselves. Everything we do has echoes in the Universe.

If we create a habit of greeting ourselves with love each morning, these first moments of our day can transform the rest of the moments of our day, our lives, and the lives of others. May this be of benefit.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Shauna Shapiro is a professor at Santa Clara University, best-selling author, and internationally recognized expert in mindfulness and compassion. Dr. Shapiro has published over 150 journal articles and co-authored three critically acclaimed books translated into 16 languages, including her most recent book: Good Morning, I Love You: Mindfulness & Self-Compassion Practices to Rewire the Brain for Calm Clarity and Joy. She has been an invited speaker for the King of Thailand, the Danish Government, Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Summit, the Canadian Government, and the World Council for Psychotherapy, as well as for Fortune 100 Companies including Google, Cisco Systems, Proctor & Gamble, and LinkedIn. The New York Times, BBC, Mashable, the Huffington Post, Wired, USA Today, and the Wall Street Journal have all featured her work. Dr. Shapiro is a summa cum laude graduate of Duke University and over 1.6 million people have watched her TEDx talk The Power of Mindfulness. More information can be found at drshaunashapiro.com.

Shauna Shapiro is a professor at Santa Clara University, best-selling author, and internationally recognized expert in mindfulness and compassion. Dr. Shapiro has published over 150 journal articles and co-authored three critically acclaimed books translated into 16 languages, including her most recent book: Good Morning, I Love You: Mindfulness & Self-Compassion Practices to Rewire the Brain for Calm Clarity and Joy. She has been an invited speaker for the King of Thailand, the Danish Government, Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Summit, the Canadian Government, and the World Council for Psychotherapy, as well as for Fortune 100 Companies including Google, Cisco Systems, Proctor & Gamble, and LinkedIn. The New York Times, BBC, Mashable, the Huffington Post, Wired, USA Today, and the Wall Street Journal have all featured her work. Dr. Shapiro is a summa cum laude graduate of Duke University and over 1.6 million people have watched her TEDx talk The Power of Mindfulness. More information can be found at drshaunashapiro.com.

Dear COVID

© 2020 Marlie Rowell

Dear COVID,

It’s really none of my business…but…does virus-validation depend exclusively on massive infection and death rates? Are you afraid retirement would diminish you? Trust me, your impact isn’t limited to the physical mayhem. With calculated caution, and in the interest of inspiring you to retire, I offer you an affirmation of sorts…I thank you for reawakening lessons I let fade.

Eleven years ago, I lost my husband to suicide. Suicide is almost as feared as you are—almost. The terror of coronavirus launched a highly visible global quest for prevention, treatment and a cure. Suicide fears manifest differently, but with equal urgency—silent urgency. Suicide usually is hushed. Shrouded in shame and fearful avoidance…oh, and stigma. Lots of unspoken stigma.

Turns out pandemics and suicides both have the power to isolate. COVID isolation revived the best in me. In the safety of solitude, I grew…not by cleaning cupboards, sweeping the garage, or organizing photos—no. Isolation reopened the sacred. OMG, hopefully this is just me…but for the love of God…I just can’t seem to hear divine wisdom while frantically grasping to control the world. Or while distracting myself with busy, busy, busy stuff. Or defiantly resisting unwelcome realities. Wish I was more evolved than this…but I can only hear be-still-and-know-wisdom when I’m on-my-knees-paralyzed. Paralyzed in fear and uncertainty. My husband’s suicide paralyzed me. Gradually I learned to surrender false feelings of control. Anguish quelled when I learned to accept…and adjust. Accept. And. Adjust. Over and over… Accept. And. Adjust.

As the years passed, healing grew…and so did a false sense of control. Slowly, I shrank back into the very trap grief taught me to reject. I returned to self-validation via seemingly measurable stuff like external productivity and shiny, trophy-equivalent thingys. Then—POW—pandemic-induced uncertainty re-paralyzed me. Fear forced me to enroll in a COVID version of: Life-Enhancment-Reproitization-101. I can’t be the only one gob-smacked with a what-if-I-die-reality-check. I can’t be the only one letting go of crap and reassessing priorities. I can’t be the only one realizing (yet again) anguish is the direct result of my own failure to repeatedly accept and adjust…

So, dear Covid, you can retire now. Today, those of us who silently enrolled in Life-Enhancment-Reproitization-101 are healthier, stronger, more lovingly human. Retire knowing you gave the entire planet the opportunity to hit pause and reevaluate what truly matters. What is precious. Cherished. Eternal. Retire knowing profound spiritual, emotional and intellectual reprioritization lives on. Retire. Let us live. Let us show you we can live kinder, more appreciative, benevolent lives.

Cheers to your retirement!

Marlie Thomas Rowell, Your Pro-Retirement Advocate

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Marlie Thomas Rowell is the creator of Suicide Widow Etiquette, an artful tool kit used to promote suicide postvention, celebrate Post Traumatic Growth, and disarm suicide phobias.

Marlie Thomas Rowell is the creator of Suicide Widow Etiquette, an artful tool kit used to promote suicide postvention, celebrate Post Traumatic Growth, and disarm suicide phobias.

A pandemic video version of Suicide Widow Etiquette as born when COVID forced her to self-sequester. If you’re brave enough to spend an hour with a suicide widow, you can. Be forewarned: the woman has zero video/tech savvy resulting in unintended comedy—entirely at her expense. Nonetheless, it’s a real-life post-suicide PTG story; a celebration of hard-earned healing and well-being. Learn more at www.suicidewidowetiquette.com and https://youtu.be/3w-nQJu5DMw.

The Bear We Must Learn to Bear

The Guilt of Saying No

© 2020 Ralph De La Rosa, LCSW

From Don’t Tell Me to Relax: Emotional Resilience in the Age of Rage, Feels, and Freak-Outs. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO.

“No” is golden. “No” is the kind of power the good witch wields. It’s the way whole, healthy, emotionally evolved people manage to have relationships with jackasses while limiting the amount of jackass in their lives.

— Cheryl Strayed

Entire precious lives have gone half-lived behind the thought, “But I don’t want to upset anybody.” Almost every well-intentioned person I know has difficulty discerning the line between this form of codependence and compassion. The list that follows is simple and even reductive but also a game-changing reminder. It is also not a moral code, and these are not maxims that are always a good idea. In fact, if you followed this list to a tee, it could be a recipe for being a terrible person. But that doesn’t erase the following truths:

- You are allowed to say no.

- You are allowed to not be nice about it.

- You are allowed to not offer any explanations as to why.

- You are allowed to not know why you are saying no.

- You are allowed to not care at all what the other person feels as a result.

- You are allowed to care about what the other person feels without taking their feelings to be your own.

- You are allowed to care about what the other person feels—and nonetheless not display to them that you care how they feel, in order to avoid getting tangled back up with that person.

- You are allowed to take measures to avoid getting tangled back up with someone after you’ve set a boundary.

- You are allowed to discern whose emotions are whose in a situation and only tend to your own.

- You are allowed to not make sense to anyone else.

- You are allowed to walk away at any time.

As you read that, a barrage of but! and what if! and I’m not ready! may have bubbled up inside you. This list is completely and utterly independent of that. None of those “buts” coming from your defensive parts erase these simple truths. Check to see if you find guilt or fear embedded in any reactions you had to reading that. You likely have something to get curious about and process here. I invite you to consider working with that fear and guilt. Working with fear and guilt is often just the price of admission to realms of personal liberation.

THE COMPASSIONATE NO

Think about the last time you said yes to something when inside of you there was really a no. Something was asked of you, perhaps to show up some place or to do something for someone, and you said yes when, in your body, there was a sensation of no. It might have seemed selfish to say no. You might have such a strong habit of giving in to others, or perhaps have even come to enjoy letting others set the agenda, that you didn’t even “hear” or “feel” the no—and yet it was there, somehow. Indeed, most of us who don’t have the greatest feel for our boundaries often don’t realize that there was a no there until after the fact. After we’ve gotten home from the draining event, after we’re already entangled in some half-hearted commitment, after a toxic person who drains us is walking all over us yet again—then we realize we made the wrong choice: that we should’ve spoken up for ourselves.

To be clear, there are situations in which we feel resistance to things that are good for us, like meditation, exercise, or spending time with someone who challenges us in healthy ways. That’s not the kind of no I’m talking about. That’s the kind of no we’d do well to get curious about, or maybe learn how to gently dance past so we can move closer to our truest desires. That kind of no is a selfish no. Being able to decipher between a selfish no and a compassionate no is part of what this chapter is about.

A compassionate no is the kind you feel when you’re asked to go to an event and you are tapped out. Or when you find yourself planning a trip to see someone, possibly a family member, who’s frequently abusive toward you. Or when you’re in the presence of someone who has drained your energy so many times in the past and here you are, feeling that sense of depletion, while fake-smiling and trying to cover up how badly you want to head for the hills. That’s the kind of no we need to heed more often in the process of reparenting ourselves.

THE BODY IS OUR COMPASS

Stop and remember a time like one of those no’s I just described. Take a breath, slow down, and really relive the experience in your mind’s eye. What happened? How did you feel? What thoughts went through your mind? What did your body feel like? Do that, take some mental notes, and then come back.

Most importantly: What happened in your body? Was there a tightness somewhere? Where was it? Was there a heaviness? An anxiety? What happened in your shoulders? In your belly? In your arms and legs? Beyond the body, can you recognize this event in general as being a pattern in your life? Maybe a pattern with this particular person or with a sort of situation that keeps repeating itself?

The bodily guidance system I’m pointing toward with these questions is that of our soma (Greek for “living body”), which is constantly talking to us, sending us signals and information. The problem is that the true, intuitive voice of the soma is often crowded out by too many competing inner voices. If we practice sensitizing ourselves to our bodies, such as with the “Grounding: Body of Breath” practice on page 94, that sense will become clearer. If we actually listen for and follow through with the guidance we’re receiving, that sense will become clearer still. And if we do the work of healing the trauma almost all of us hold in our bodies, that voice will begin to get loud and clear as a bell.

It’s important to think of checking in with your bodily felt sense as a practice, because there’s plenty of momentum in the habit of saying yes. When it comes to saying no and holding boundaries, the fear of feeling guilty is perhaps the number one overriding force of our sense of no. We don’t want to let anyone down. We fear what they might think of us. We fear the backlash. We fear what might happen to someone if we don’t show up or help in some way. We see someone with a need we technically could help them address, and so we feel it’s our responsibility. We feel obligated. All of this means that there’s a certain tenderness we have to cultivate in saying “no.” We can learn to acknowledge that we truly want to be helpful people, responsive people, and that doing so involves saying “no” much more than we thought it did.

In countless sessions, clients have told me about painfully tangled interpersonal webs they find themselves in. I typically ask, “Why didn’t you say no?” only to have the response come back, “I would’ve felt guilty.” My follow-up question: “Which is worse, the situation you’re in now or the guilt you would have felt?” Which one is more intense? Which one lasts longer? Guilt is indeed a bear of an emotion: a formidable beast we dread meeting with in the vast forest of life, but we must learn to hold it. We must learn to bear the bear of guilt if we want to stay true to ourselves and not cause harm with our codependency, however subtle. Holding space for the bear of guilt is often one of the kindest things we can do—for ourselves, for those with whom we’re in codependent relationships, and as an example to others.

That’s step one: to be willing to feel the guilt in the wake of saying no or holding some sort of boundary. Step two would be to acknowledge the toxic shame embedded in the guilt and to offer the energy of curiosity or self-love to that part of you.

DUCK BREAD

There’s one last consequence that I’d like to discuss about saying yes even when you feel a no in your body. It’s the most common one: resentment.

Marshall Rosenberg, author of Nonviolent Communication, discusses the concept of memnoon, an Arabic word that roughly translates to “the request that blesses the giver.” Rosenberg translates this as, “Please do as I request only if you can do so with the joy of a little child feeding bread to a hungry duck. Please do not do as I request if there is any taint of fear of punishment . . . [or] you would feel guilty if you don’t.” A client of mine once abbreviated this to “duck bread” so that it’d be easier to remember. Basically, if we’re not feeling a full yes about something, it might be best to say no and to bear whatever comes up as a result. After all, would you want somebody showing up for you begrudgingly? Or only because they feel obligated to? Or, worse yet, only because they fear being on the receiving end of you shaming them if they don’t?

When interactions are imbalanced in this manner, an iota of resentment is generated and stored away. Over time, with repeated experiences such as this, those iotas really begin to add up. Resentment is one of the greatest usurpers of love and affection on the planet. I can’t tell you how many couples have landed on my therapy couch full of stored resentments that have slowly eaten away at what was once a beautiful and nourishing connection. I find consistently in such situations that one or both of them have long been tolerating and bottling things they should have refused at the onset. But they didn’t. What could have been a simple, “Hey, that doesn’t work for me, can we find another way?” years ago is now a seething heap of layered complexities of the kind that so often, and so heartbreakingly, never gets resolved.

Some friends of mine live in an intentional community in Brooklyn where they have a custom: when someone says no to something, to anything, the other person responds, “Thank you for taking care of yourself.” This practice is borne of the awareness that if you don’t take care of you, I’ll end up having to do that in some way down the line. If your plate is already too full and you don’t express your no to my birthday party or performance or brunch invitation—if you say yes instead—I might get my way, but the price tag of resentment in our relationship is just too expensive.

“No” is often the most compassionate option on the table. But, as mentioned above, it will be difficult to connect with that soft, inner voice that says “no” if we’re strongly habituated to saying “yes.” This practice becomes so much easier when we devote some time to practices of embodiment that help us sense ourselves with greater refinement.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ralph De La Rosa, LCSW, is a psychotherapist in private practice and a seasoned meditation instructor. His work has been featured in the New York Post, CNN, GQ, SELF, Women’s Health, and many other publications and podcasts. He regularly leads immersive healing retreats at Omega Institute, Spirit Rock, and Kripalu. He is a summa cum laude graduate of Fordham University’s social work program and has trained in multiple forms of trauma-focused treatment including Internal Family Systems therapy (IFS) and Somatic Experiencing (SE). For more, please visit www.ralphdelarosa.com.

Ralph De La Rosa, LCSW, is a psychotherapist in private practice and a seasoned meditation instructor. His work has been featured in the New York Post, CNN, GQ, SELF, Women’s Health, and many other publications and podcasts. He regularly leads immersive healing retreats at Omega Institute, Spirit Rock, and Kripalu. He is a summa cum laude graduate of Fordham University’s social work program and has trained in multiple forms of trauma-focused treatment including Internal Family Systems therapy (IFS) and Somatic Experiencing (SE). For more, please visit www.ralphdelarosa.com.

Mindfulness and Mindlessness: A Neuroscientist’s Perspective

© 2020 Brian Pennie

I spent most of my life mindlessly obsessing about the past and the future. I was consumed by anxiety and tormented by my mind, but completely unaware of the source of my suffering. To escape my pain, I used drugs, resulting in 15 years of chronic heroin addiction. Heroin brought me to the very edge, but I was lucky. Pounded into submission by the most painful night of my life, I was forced to look at the world from a completely new perspective. That was in October 2013, when I was first introduced to mindfulness. Since then, with no small thanks to Dr. Rick Hanson for his book, Buddha’s Brain, I’ve become an author, a Ph.D. student, and a lecturer at the top two universities in Ireland, all in the area of the neuroscience of mindfulness. Understanding the science underlying mindfulness and meditation can be a powerful motivation for anyone building these habits. But it’s especially helpful if you’re the kind of person who wants evidence of efficacy before embarking on a new goal. How the Brain Works Neurons Neurons are the basic building blocks of your brain, and there are about 86 billion of them. A single neuron fires between five and fifty times per second, and on average, each neuron receives five thousand connections from other neurons. So, in the time it takes you to read this sentence, billions of neurons will have fired inside your head — a complex system, to put it mildly. For every action, thought, and feeling you will ever have, it’s neurons firing that allow you to make sense of the experience. This is the biological basis of learning. The more you practice a certain behavior — say, mindfulness, or worry — associated neurons become more practiced. These neurons are then required to fire more often and more quickly. To save energy, the brain creates new structures specific to the job at hand. This is the essence of learning, and what we call neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity Our brains are malleable, like playdough, and our experiences determine their shape. This process is best compared to physical exercise. For example, thirty reps in a gym won’t make your muscles bigger, but thirty reps every day for a year will. The same is true for your brain, and over time, its shape will change. As a perennial worrier, I always felt tense, uneasy, and anxious. If my mind wasn’t scanning the world for potential threats, it was looking for ways to relieve my unrelenting anxiety. Over time, I literally transformed my brain into a finely tuned anxiety machine. It’s the same for any negative feelings, thoughts, and emotions. Whatever you rest your mind upon, be it anger, self-doubt, or fear, your brain will eventually take that shape. The reptilian brain The human brain can be loosely divided into three regions: the reptilian brain, the limbic brain, and the cortex. The reptilian brain, the oldest of the three brain regions from an evolutionary perspective, is responsible for the body’s vital functions, such as body temperature, heart rate, and breathing. This structure is also in control of our instinctual and self-preserving behaviors, which ensure the survival of the species. This primitive part of the brain, which is also responsible for reckless and impulsive behavior, can be highly problematic. Its need to survive is so powerful that it often fights with the logical part of the brain, the cortex.  It’s like two different people having an argument. “Go on, have a drink.” “No, I better not.” “Ah, sure I deserve it.” “Yeah, but you’ll regret it later.” If you’re an anxious person, as I was, the reptile brain sees feelings of anxiety as a threat, even when it doesn’t know what’s causing them. Through experience, it knows that a drink can relieve anxiety, if only for a short while. So when you say yes to that drink, the reptilian brain has won. I often think back on my drug-induced years when my impulsive behavior was controlled by my reptilian brain. There was never a fight, just a winner — the crocodile always got his drugs. The limbic brain The limbic brain is comprised of several structures, found above the reptilian brain. The main components include the hippocampus, the amygdala, and the hypothalamus. The limbic brain supports a variety of functions. The hippocampus is essential for memory formation. The amygdala, located next to the hippocampus, plays a key role in emotions like fear, anxiety, and anger. The amygdala is also responsible for determining the strength of stored memories, whereby memories with strong emotional content tend to stick. The hypothalamus, which links the brain to the endocrine system, is a vital component of our stress response. It produces chemical messengers that can both stimulate or inhibit stress-releasing hormones. The cortex The cortex, the most recent addition of the three brain regions, consists of grey matter surrounding the deeper white matter of the cerebrum. Grey matter contains the bodies of neurons, and white matter consists of the connecting fibers between different grey matter cells.

It’s like two different people having an argument. “Go on, have a drink.” “No, I better not.” “Ah, sure I deserve it.” “Yeah, but you’ll regret it later.” If you’re an anxious person, as I was, the reptile brain sees feelings of anxiety as a threat, even when it doesn’t know what’s causing them. Through experience, it knows that a drink can relieve anxiety, if only for a short while. So when you say yes to that drink, the reptilian brain has won. I often think back on my drug-induced years when my impulsive behavior was controlled by my reptilian brain. There was never a fight, just a winner — the crocodile always got his drugs. The limbic brain The limbic brain is comprised of several structures, found above the reptilian brain. The main components include the hippocampus, the amygdala, and the hypothalamus. The limbic brain supports a variety of functions. The hippocampus is essential for memory formation. The amygdala, located next to the hippocampus, plays a key role in emotions like fear, anxiety, and anger. The amygdala is also responsible for determining the strength of stored memories, whereby memories with strong emotional content tend to stick. The hypothalamus, which links the brain to the endocrine system, is a vital component of our stress response. It produces chemical messengers that can both stimulate or inhibit stress-releasing hormones. The cortex The cortex, the most recent addition of the three brain regions, consists of grey matter surrounding the deeper white matter of the cerebrum. Grey matter contains the bodies of neurons, and white matter consists of the connecting fibers between different grey matter cells.  The cortex is the part of the brain involved in higher-order functioning, such as abstract thought, problem-solving, appraisal of danger, and language. With unparalleled learning capacities, this highly flexible structure has enabled humans to do things no other species has done. The stress response In times of stress, the three core structures of the limbic system — the hippocampus, the amygdala, and the hypothalamus — work together in tandem. Consider this example. You are walking through a field when you see what looks like a snake. Stored memories in the hippocampus remind you that you’re scared of snakes. This lights up your amygdala — the fear center of your brain — which activates your hypothalamus. The hypothalamus then sends a signal to your pituitary glands, which in turn, sends a message to your adrenal glands releasing cortisol throughout your bloodstream. Cortisol is the primary stress hormone, which prepares your body for fight or flight. The Neuroscience of Mindlessness It’s not life or death The cortex, the reptilian brain, and the limbic brain collectively work together. They are interconnected by complex neural pathways (white matter) that have developed to influence one another. In the snake example above, a survival response from the reptilian brain would have activated the limbic system, releasing cortisol throughout your body. This speedy bodily response is what gets you out of immediate or potential danger. At the same time, however, the rational part of the brain, the cortex, appraises the situation. This is a slower process, and if you’re lucky, you realize that the snake is actually a piece of rubber. When this happens, the cortex deactivates the amygdala, which in turn inhibits the secretion of cortisol via the hypothalamus, thus bringing the body back into homeostasis.

The cortex is the part of the brain involved in higher-order functioning, such as abstract thought, problem-solving, appraisal of danger, and language. With unparalleled learning capacities, this highly flexible structure has enabled humans to do things no other species has done. The stress response In times of stress, the three core structures of the limbic system — the hippocampus, the amygdala, and the hypothalamus — work together in tandem. Consider this example. You are walking through a field when you see what looks like a snake. Stored memories in the hippocampus remind you that you’re scared of snakes. This lights up your amygdala — the fear center of your brain — which activates your hypothalamus. The hypothalamus then sends a signal to your pituitary glands, which in turn, sends a message to your adrenal glands releasing cortisol throughout your bloodstream. Cortisol is the primary stress hormone, which prepares your body for fight or flight. The Neuroscience of Mindlessness It’s not life or death The cortex, the reptilian brain, and the limbic brain collectively work together. They are interconnected by complex neural pathways (white matter) that have developed to influence one another. In the snake example above, a survival response from the reptilian brain would have activated the limbic system, releasing cortisol throughout your body. This speedy bodily response is what gets you out of immediate or potential danger. At the same time, however, the rational part of the brain, the cortex, appraises the situation. This is a slower process, and if you’re lucky, you realize that the snake is actually a piece of rubber. When this happens, the cortex deactivates the amygdala, which in turn inhibits the secretion of cortisol via the hypothalamus, thus bringing the body back into homeostasis.  This is a very simple example, but in real life, things are never quite so black and white, especially in today’s busy world. When I think of how this relates to the old anxiety and addiction ravaged me, I get a headache. But let’s give it a go. My anxiety, which resulted from childhood trauma, centered on bodily sensations. Ever since I can remember, I was terrified of my heartbeat, breath, and pulse. If someone asked me to feel my own heartbeat, or if I even talked about it, my amygdala lit up like a Christmas tree. The reptilian brain, always thinking of self-preservation, said: “Right, I’ll get you out of this shit, pal.” So what did I do? Anything to get away from myself, anything to quieten my overactive mind — and for me, that was drugs. I often wonder what my rational mind, the cortex, was doing during this time. My heartbeat wasn’t going to kill me. I was never in any real danger. Surely my logical mind knew this. Wasn’t it supposed to tell my limbic system that everything was OK? Neuroscience provides us with many potential theories to explain these questions. The cortex might be worked too hard by an overactive limbic system, or simply unable to use logic to eliminate irrational fears. The truth is, we don’t know for sure, but understanding the basic mechanics of this system has provided me with a framework to realize that there is nothing to worry about — certainly not life or death stuff anyway.

This is a very simple example, but in real life, things are never quite so black and white, especially in today’s busy world. When I think of how this relates to the old anxiety and addiction ravaged me, I get a headache. But let’s give it a go. My anxiety, which resulted from childhood trauma, centered on bodily sensations. Ever since I can remember, I was terrified of my heartbeat, breath, and pulse. If someone asked me to feel my own heartbeat, or if I even talked about it, my amygdala lit up like a Christmas tree. The reptilian brain, always thinking of self-preservation, said: “Right, I’ll get you out of this shit, pal.” So what did I do? Anything to get away from myself, anything to quieten my overactive mind — and for me, that was drugs. I often wonder what my rational mind, the cortex, was doing during this time. My heartbeat wasn’t going to kill me. I was never in any real danger. Surely my logical mind knew this. Wasn’t it supposed to tell my limbic system that everything was OK? Neuroscience provides us with many potential theories to explain these questions. The cortex might be worked too hard by an overactive limbic system, or simply unable to use logic to eliminate irrational fears. The truth is, we don’t know for sure, but understanding the basic mechanics of this system has provided me with a framework to realize that there is nothing to worry about — certainly not life or death stuff anyway.  Emotional hijacking Have you ever felt completely shaken and overcome by fear? I have. I was easily overwhelmed before and during my addiction — it was my default. Daniel Goleman calls this an emotional hijacking, where your amygdala screams like a siren. This happens when something in your environment triggers a stress response. It might be your partner raising their voice, a work colleague criticizing you, a close call on the road, or someone giving you a fright. From a neuroscience perspective, the visual or auditory cortex — depending on whether it was a visual or verbal stimulus — sends a message to your amygdala, and a stress response is activated. You would think this is how most people experience stress, and it was certainly how it evolved in our species. But in today’s busy world, more often than not, the stress response is not activated by the external environment — it is activated by our own minds. This comes in two flavors: ruminating about a past you cannot change, and worrying about an imaginary future. These internal stressors are the worst kind of triggers. External stressors come and go, but fighting with your own mind is constant. And when it comes to stress, it’s like forgetting to tighten the cortisol tap when you leave the bathroom…drip, drip, drip. The Neuroscience of Mindfulness

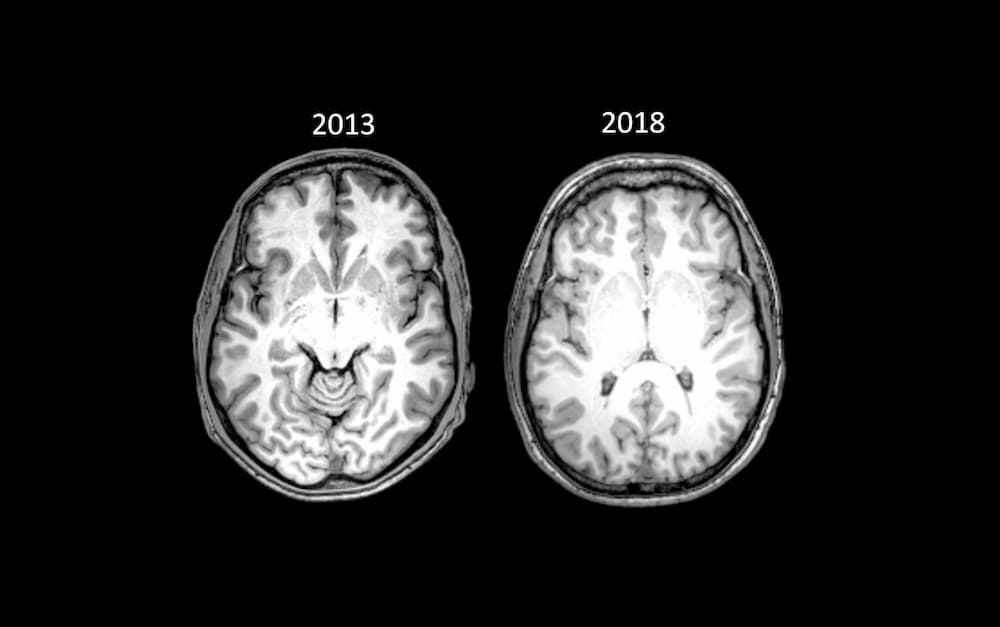

Emotional hijacking Have you ever felt completely shaken and overcome by fear? I have. I was easily overwhelmed before and during my addiction — it was my default. Daniel Goleman calls this an emotional hijacking, where your amygdala screams like a siren. This happens when something in your environment triggers a stress response. It might be your partner raising their voice, a work colleague criticizing you, a close call on the road, or someone giving you a fright. From a neuroscience perspective, the visual or auditory cortex — depending on whether it was a visual or verbal stimulus — sends a message to your amygdala, and a stress response is activated. You would think this is how most people experience stress, and it was certainly how it evolved in our species. But in today’s busy world, more often than not, the stress response is not activated by the external environment — it is activated by our own minds. This comes in two flavors: ruminating about a past you cannot change, and worrying about an imaginary future. These internal stressors are the worst kind of triggers. External stressors come and go, but fighting with your own mind is constant. And when it comes to stress, it’s like forgetting to tighten the cortisol tap when you leave the bathroom…drip, drip, drip. The Neuroscience of Mindfulness  If you're persistently anxious, angry, or self-loathing, your brain will eventually take that shape. At the same time, however, you can shape your brain in a much more positive direction. By harnessing the power of neuroplasticity via regular mindfulness practice, you can become more resilient, develop sharper focus, and manage your emotions more effectively. The images below are scans of my own brain. The one on the left was conducted as part of a study in 2013 — when I was only two days clean, after 15 years of addiction. The one on the right was taken in May 2018 as part of a TV documentary about stress.

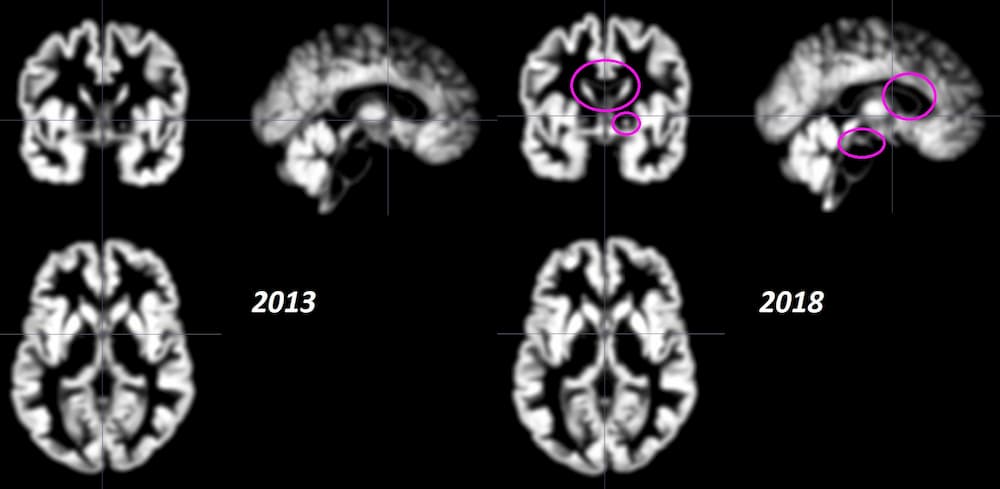

If you're persistently anxious, angry, or self-loathing, your brain will eventually take that shape. At the same time, however, you can shape your brain in a much more positive direction. By harnessing the power of neuroplasticity via regular mindfulness practice, you can become more resilient, develop sharper focus, and manage your emotions more effectively. The images below are scans of my own brain. The one on the left was conducted as part of a study in 2013 — when I was only two days clean, after 15 years of addiction. The one on the right was taken in May 2018 as part of a TV documentary about stress.  Source: Unprocessed scans of my brain taken in 2013 and 2018. These scans contain the slice showing the anterior commissure, the standard anatomical structure used to compare brain scans. It was difficult to make exact slice comparisons as the images were scanned on different MRI machines using a different resolution. My brain was so different that the person analyzing the scans could not compare the standard visual markers by eye (see the note above for a more technical explanation). Our lab at Trinity College Institute of Neuroscience has also worked on various methods to predict brain age. We calculate brain-predicted age (brainPAD scores) by analyzing the grey matter density of the brain. This is associated with increased mortality risk, cognitive decline, increased risk of dementia, and poorer physical function. In 2013, my predicted brain-age was 2.84 years ‘younger’ than my chronological age. This was surprising after 15 years of drug addiction. In 2018, however, my brain was just under 10 years ‘younger’ than my chronological age. In the 5 years between scans, this means I reduced the age of my brain by more than 6 years. It’s difficult to visually identify differences in grey-matter density, but if you look closely, you can see specific differences in the purple circles below. The scans on the right also look brighter all round.

Source: Unprocessed scans of my brain taken in 2013 and 2018. These scans contain the slice showing the anterior commissure, the standard anatomical structure used to compare brain scans. It was difficult to make exact slice comparisons as the images were scanned on different MRI machines using a different resolution. My brain was so different that the person analyzing the scans could not compare the standard visual markers by eye (see the note above for a more technical explanation). Our lab at Trinity College Institute of Neuroscience has also worked on various methods to predict brain age. We calculate brain-predicted age (brainPAD scores) by analyzing the grey matter density of the brain. This is associated with increased mortality risk, cognitive decline, increased risk of dementia, and poorer physical function. In 2013, my predicted brain-age was 2.84 years ‘younger’ than my chronological age. This was surprising after 15 years of drug addiction. In 2018, however, my brain was just under 10 years ‘younger’ than my chronological age. In the 5 years between scans, this means I reduced the age of my brain by more than 6 years. It’s difficult to visually identify differences in grey-matter density, but if you look closely, you can see specific differences in the purple circles below. The scans on the right also look brighter all round.  Source: Grey matter scans of my brain taken in 2013 and 2018. Although subtle, there is greater grey matter density in the scan from 2018. Unlike the comparison scans above, these scans have been processed using a normalization technique which is required for the analysis. It is difficult to specifically account for what caused these changes. In the four and a half years between the scans, I radically overhauled many aspects of my life, including diet, exercise, and sleep. I also went back to college and, of course, I stopped taking heroin. But for me, present moment awareness provided the foundations for all of these changes. From the day I was introduced to mindfulness, everything changed. It gave me a tool to cope with my greatest adversary, anxiety, and everything just flowed from there. Emotional regulation Research shows that a regular mindfulness practice significantly weakens the amygdala’s ability to hijack your emotions. This happens in two ways. First, the amygdala decreases in physical size. Second, connections between the amygdala and the parts of the cortex associated with fear are weakened, while connections associated with higher-order brain functions (i.e. self-awareness) are strengthened. My own mindfulness practice has given me both of these gifts. I have literally shrunk the fear centre of my brain, and as a result, I simply don’t feel fear and anxiety like I used to. Stressful events still challenge me, but by creating a space between stimulus and response, I am no longer hijacked by my emotions. Attention and focus The area of the brain associated with attention is a structure called the anterior cingulate cortex. It has also been linked to self-regulation and flexible thinking — the opposite of compulsive and rigid thinking. Research has found increased volume in this area of the brain after mindfulness practice. What’s more, when the connections between the amygdala and the rest of the cortex get weaker (i.e. the areas associated emotional hi-jacking), attentional control becomes stronger. One study showed that practicing mindfulness for only 20 minutes per day for five days can lead to improvements in attention, while a more recent study showed that a brief mindfulness intervention improves attention in complete novices. Self-awareness “Self” means your self-concept, your story — who you think you are. If you are suffering in some way, like I was with anxiety, disconnecting from “self” will give you the freedom to experience a greater sense of wellbeing. Through improved self-awareness, mindfulness can provide a detachment from the self. Instead of being controlled by your self-concept, an ability to observe or experience the old you will emerge. Although research in this area is only just emerging, some promising studies have targeted an area known as the default mode network (DMN), also known as the wandering “Monkey Mind”. The DMN is active when our minds are directionless, aimlessly drifting from thought to thought. This has been linked to rumination and overthinking, which can be extremely counterproductive to our personal wellbeing. Mindfulness has been found to decrease activation of the DMN, and in effect, to quieten our busy minds. In one study, regions of the DMN showed reduced activation in meditators compared to non-meditators, which has been interpreted as a diminished reference to self. Simple Steps to Get Real Results Psychological phenomena, such as stress, rumination, and anxiety, are often thought of as abstract concepts that you cannot touch, feel, or see. But the fact is, these experiences are firmly grounded in biology. Fortunately, so is mindfulness, which appears to provide a potential solution for much of the suffering in today’s modern world. Having struggled with anxiety and addiction for most of my life, I have witnessed the power of mindfulness as it has helped me to thrive with a newfound lust for life. If you or someone you know is battling addiction and seeking detox assistance, click here for help. By practicing mindfulness on a regular basis, I not only feel better, but I have also physically altered the structure and function of my brain. I’m no longer anxious, I no longer worry, and I’m more focused and aware than ever before. Bad habits are hard to break, but guess what: so are good ones. Anxiety has been replaced by a sense of calm — my new default — which is now entrenched in the physical fibers of my brain. Changing the shape of your brain, and therefore how you think and feel, is there for anyone. All you have to do is introduce regular mindfulness practices into your life. Stick with it for just 10 minutes per day. My one ask is that you do it every single day. Building this habit is crucial if you want to change your brain, but for increased awareness, focus, and emotional control, I don’t think that’s too big of an ask.

Source: Grey matter scans of my brain taken in 2013 and 2018. Although subtle, there is greater grey matter density in the scan from 2018. Unlike the comparison scans above, these scans have been processed using a normalization technique which is required for the analysis. It is difficult to specifically account for what caused these changes. In the four and a half years between the scans, I radically overhauled many aspects of my life, including diet, exercise, and sleep. I also went back to college and, of course, I stopped taking heroin. But for me, present moment awareness provided the foundations for all of these changes. From the day I was introduced to mindfulness, everything changed. It gave me a tool to cope with my greatest adversary, anxiety, and everything just flowed from there. Emotional regulation Research shows that a regular mindfulness practice significantly weakens the amygdala’s ability to hijack your emotions. This happens in two ways. First, the amygdala decreases in physical size. Second, connections between the amygdala and the parts of the cortex associated with fear are weakened, while connections associated with higher-order brain functions (i.e. self-awareness) are strengthened. My own mindfulness practice has given me both of these gifts. I have literally shrunk the fear centre of my brain, and as a result, I simply don’t feel fear and anxiety like I used to. Stressful events still challenge me, but by creating a space between stimulus and response, I am no longer hijacked by my emotions. Attention and focus The area of the brain associated with attention is a structure called the anterior cingulate cortex. It has also been linked to self-regulation and flexible thinking — the opposite of compulsive and rigid thinking. Research has found increased volume in this area of the brain after mindfulness practice. What’s more, when the connections between the amygdala and the rest of the cortex get weaker (i.e. the areas associated emotional hi-jacking), attentional control becomes stronger. One study showed that practicing mindfulness for only 20 minutes per day for five days can lead to improvements in attention, while a more recent study showed that a brief mindfulness intervention improves attention in complete novices. Self-awareness “Self” means your self-concept, your story — who you think you are. If you are suffering in some way, like I was with anxiety, disconnecting from “self” will give you the freedom to experience a greater sense of wellbeing. Through improved self-awareness, mindfulness can provide a detachment from the self. Instead of being controlled by your self-concept, an ability to observe or experience the old you will emerge. Although research in this area is only just emerging, some promising studies have targeted an area known as the default mode network (DMN), also known as the wandering “Monkey Mind”. The DMN is active when our minds are directionless, aimlessly drifting from thought to thought. This has been linked to rumination and overthinking, which can be extremely counterproductive to our personal wellbeing. Mindfulness has been found to decrease activation of the DMN, and in effect, to quieten our busy minds. In one study, regions of the DMN showed reduced activation in meditators compared to non-meditators, which has been interpreted as a diminished reference to self. Simple Steps to Get Real Results Psychological phenomena, such as stress, rumination, and anxiety, are often thought of as abstract concepts that you cannot touch, feel, or see. But the fact is, these experiences are firmly grounded in biology. Fortunately, so is mindfulness, which appears to provide a potential solution for much of the suffering in today’s modern world. Having struggled with anxiety and addiction for most of my life, I have witnessed the power of mindfulness as it has helped me to thrive with a newfound lust for life. If you or someone you know is battling addiction and seeking detox assistance, click here for help. By practicing mindfulness on a regular basis, I not only feel better, but I have also physically altered the structure and function of my brain. I’m no longer anxious, I no longer worry, and I’m more focused and aware than ever before. Bad habits are hard to break, but guess what: so are good ones. Anxiety has been replaced by a sense of calm — my new default — which is now entrenched in the physical fibers of my brain. Changing the shape of your brain, and therefore how you think and feel, is there for anyone. All you have to do is introduce regular mindfulness practices into your life. Stick with it for just 10 minutes per day. My one ask is that you do it every single day. Building this habit is crucial if you want to change your brain, but for increased awareness, focus, and emotional control, I don’t think that’s too big of an ask.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

On October 8, 2013, Brian Pennie experienced his first day clean after 15 years of chronic heroin addiction. Instead of perceiving his addiction as a failure, he embraced a second chance at life and went to university to study the intricacies of human behavior. Since then, Brian has become a keynote speaker, a PhD student, a life change strategist, a radio presenter on Dublin City FM, and a university lecturer in Trinity College and University College Dublin, where he teaches the neuroscience of mindfulness and addiction. He is also a published academic author and he has just released his first book, a memoir called Bonus Time. Brian also writes regularly about the tools, habits, and tactics that transformed his life. You can find his work via his website.

On October 8, 2013, Brian Pennie experienced his first day clean after 15 years of chronic heroin addiction. Instead of perceiving his addiction as a failure, he embraced a second chance at life and went to university to study the intricacies of human behavior. Since then, Brian has become a keynote speaker, a PhD student, a life change strategist, a radio presenter on Dublin City FM, and a university lecturer in Trinity College and University College Dublin, where he teaches the neuroscience of mindfulness and addiction. He is also a published academic author and he has just released his first book, a memoir called Bonus Time. Brian also writes regularly about the tools, habits, and tactics that transformed his life. You can find his work via his website.

Fare Well

May you and all beings be happy, loving, and wise.

Perspectives on Self-Care

Be careful with all self-help methods (including those presented in this Bulletin), which are no substitute for working with a licensed healthcare practitioner. People vary, and what works for someone else may not be a good fit for you. When you try something, start slowly and carefully, and stop immediately if it feels bad or makes things worse.