News and Tools for

Happiness, Love, and Wisdom

Volume 15.4 • August 2021

In This Issue

The Hidden Gifts of Addiction

© 2021 Victor Bucklew, PhD

Certain sections adapted with permission from the Nautilus award winning book, The Hidden Gifts of Addiction: The Direct Path of Recovery, Rock Creek Canyon Publishing.

* * *

The Many Shades of Addiction

Most of us have felt trapped at one time or another in an addictive cycle. Some of us may feel currently trapped. Whether we turn to substances, alcohol, food, screens, sex, people, thought, or compulsive behavior, the suffering of addiction is no stranger. However, what if addiction was more than just its overt forms such as substance abuse, gambling, etc? Addiction is not only as black and white as it is portrayed. When we deeply explore our addictive patterns, we discover at their core a natural yet unconscious resistance to the present moment. The forms this resistance can take—which appear in the unique ways that we reach for, push away, or numb ourselves from fully experiencing this moment—are infinite in number. If you're currently struggling with addiction, you may need to look for professional treatment services. Carrara Treatment Center in Malibu specializes in luxury substance abuse treatment. Their programs offer a blend of effective treatment and luxury amenities. Those who are struggling with cocaine addiction may get in touch with a specialist rehab centre. For instance, right now while reading you may be able to tune into the presence of the energy of addiction within you. It may appear as a subtle fast-paced need to push ahead and figure out whether this read will be worth your time. Or, maybe as dullness—a checking out that leaves a sense of mental fogginess and emotional aloofness in wake. You may find yourself skimming these words. Or, addiction might emerge more viscerally as a sensation of clenching in the head—a painful yet protective judgment that might assert, “Who is this person to say something to me about addiction? I know what addiction is. I’ve lived through it.” Or even more painfully, “My loved one, friend, or client did not.” My friend, you are not alone. As painful as these responses can be, they are absolutely expected. Moreover, they are not problems. When we slow down enough to feel into the energy of addiction within ourselves, we find that it underlies and permeates most aspects of our waking lives. The energy of addiction is everywhere in our modern, globalized world. As the result of our culture’s discomfort and fear of addiction, we allow it to play mostly destructive roles in our lives. However, if we choose to slow down, turn towards, and gradually become intimate with the energy of addiction within us on a more fundamental level, what might we discover in the process? In this article, you are invited into a heart-centered contemplation of this question.

My Story

Greetings

The Wise Brain Bulletin offers skillful means from brain science and contemplative practice – to nurture your brain for the benefit of yourself and everyone you touch.

The Bulletin is offered freely, and you are welcome to share it with others. Past issues are posted at http://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin. Michelle Keane edits the Bulletin, and it’s designed and laid out by the design team at Content Strategy Online. To subscribe, go to http://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin.

Before beginning, I’d like to briefly share my journey with you, as this inquiry into addiction is dear to my heart. Thirteen years ago, while waking up the morning after Christmas, I heard a voice I had never heard before but which I recognized as my own. It softly told me I never needed to use heroin again. And I haven’t. The voice carried the power to actualize the possibility. Even though I knew I would not use again, I did not know how I would live. My seven-year opiate addiction and the hundreds of attempts to quit, followed by withdrawal and the inevitable relapse, had been a sort of death. I’d spent so much time living in darkness that I didn’t believe there was any other way to live. When I stopped using, everything I had been numbing came to the surface. Amidst the suffering I experienced in early recovery, I was haunted by questions about the deeper roots of my addiction, who I was without using, and if it was possible to feel peace while clean and sober. If you have also started your addiction recovery journey, you may seek support from a sober living in orange county. About two years into sobriety, after persevering through 12-step programs and multiple courses of therapy, I noticed I no longer had cravings to use. But I also saw that, despite the healing I was experiencing, I had unknowingly become addicted to exercise. I wasn’t able to sleep unless I vigorously exercised a few hours every day. Although exercise was healthy and important for my wellness, I was using it to numb. If I went without exercise for even a day, I felt unnerved by tremendous anxiety.  A light bulb went off: I was not using substances any longer, yet I was not free of addiction. The healing techniques I practiced on a daily basis were helping me stay clean and sober, but the root of addiction, I now saw, lay deeper than the overt behaviors that were commonly discussed in therapy and recovery circles. I knew there had to be more to recovery and healing than sobriety. I loved this insight, for it marked the beginning of a deeper, more holistic path to recovery. Known for innovative, high-end treatment, 1 Method Rehab Los Angeles tailors luxury rehab services for comprehensive, effective recovery. As I continued to benefit from both traditional and nontraditional paths of healing (12-step programs, intensive yoga practice, Western and Eastern medicine, psychotherapy, music, body and energy work, and meditation), I became increasingly fascinated with exploring addiction at its root. I intuited that if I could understand addiction on a more fundamental level, that would in itself be healing. I share the above not as a blueprint for cleaning up or recovery–which will look differently for each of us–but because this living inquiry into the root of addiction has been dear to me for many years. In this article, I invite you to explore it with me. Our inquiry in the article will traverse four parts: 1) a brief introduction to working with addiction through meditative inquiry and reading; 2) a reframing of addiction and the potential gifts of its healing; 3) an inquiry into what healing from addiction means, and; 4) an inquiry into what addiction is asking for in your life.

A light bulb went off: I was not using substances any longer, yet I was not free of addiction. The healing techniques I practiced on a daily basis were helping me stay clean and sober, but the root of addiction, I now saw, lay deeper than the overt behaviors that were commonly discussed in therapy and recovery circles. I knew there had to be more to recovery and healing than sobriety. I loved this insight, for it marked the beginning of a deeper, more holistic path to recovery. Known for innovative, high-end treatment, 1 Method Rehab Los Angeles tailors luxury rehab services for comprehensive, effective recovery. As I continued to benefit from both traditional and nontraditional paths of healing (12-step programs, intensive yoga practice, Western and Eastern medicine, psychotherapy, music, body and energy work, and meditation), I became increasingly fascinated with exploring addiction at its root. I intuited that if I could understand addiction on a more fundamental level, that would in itself be healing. I share the above not as a blueprint for cleaning up or recovery–which will look differently for each of us–but because this living inquiry into the root of addiction has been dear to me for many years. In this article, I invite you to explore it with me. Our inquiry in the article will traverse four parts: 1) a brief introduction to working with addiction through meditative inquiry and reading; 2) a reframing of addiction and the potential gifts of its healing; 3) an inquiry into what healing from addiction means, and; 4) an inquiry into what addiction is asking for in your life.

Reading this Article: A Meditation on Addiction

Let’s begin by considering how the process of reading this article may be approached as a meditative practice that—in and of itself—may shed light on addictive patterns. We are often trained to consume the written word quickly, even excessively, and so reading is an excellent, low-risk activity to be with the energy of addiction. (Note that this practice is intended to be playful, and with a gentle touch. If you find yourself overly stressed by this exploration, please listen to your needs.) While reading, you are invited to approach the process of reading as a simple and direct meditation—a kind of open listening. Words like “receiving” and “inner listening” will be used to help you practice this attentive yet relaxed way of reading.  For instance, while reading certain passages, you may notice the emergence of clenching or resistance. You may notice the energy of addiction within. If this happens, put the article down. Give yourself to the resistance. Can you see what it is like to explore it, become interested in, and perhaps even appreciate it? How curious for resistance to emerge! And if a feeling of wonder or warmth is present, how is that for you? How does it feel to connect with your open heart? What conditions of heart, mind, and body are present for you in these moments? Although there is certainly a preference for feeling open-hearted, we can discover a soft joy in simply being with whatever arises, even if that whatever includes difficulty and challenging emotion. Clearly this is not a way that most of us typically read. Most of us are more familiar with the style of reading encouraged by modern consumer culture—consumptive, fast-paced, and addictive. To help facilitate this process, this article has been formatted to provide space for your inner experience to emerge more fully while you are reading. You are invited to rest in the space between paragraphs, and to discover a new rhythm and pace of reading. When we read in this way, the rhythm often fluctuates, but the pace tends to be slower than what most of us are accustomed to. At various points, I’ve also inserted typographical breaks in the text, like the one below this paragraph, to serve as an invitation for a longer pause. In these breaks, feel free to put the article down, and rest in whatever your experience of the moment may be.

For instance, while reading certain passages, you may notice the emergence of clenching or resistance. You may notice the energy of addiction within. If this happens, put the article down. Give yourself to the resistance. Can you see what it is like to explore it, become interested in, and perhaps even appreciate it? How curious for resistance to emerge! And if a feeling of wonder or warmth is present, how is that for you? How does it feel to connect with your open heart? What conditions of heart, mind, and body are present for you in these moments? Although there is certainly a preference for feeling open-hearted, we can discover a soft joy in simply being with whatever arises, even if that whatever includes difficulty and challenging emotion. Clearly this is not a way that most of us typically read. Most of us are more familiar with the style of reading encouraged by modern consumer culture—consumptive, fast-paced, and addictive. To help facilitate this process, this article has been formatted to provide space for your inner experience to emerge more fully while you are reading. You are invited to rest in the space between paragraphs, and to discover a new rhythm and pace of reading. When we read in this way, the rhythm often fluctuates, but the pace tends to be slower than what most of us are accustomed to. At various points, I’ve also inserted typographical breaks in the text, like the one below this paragraph, to serve as an invitation for a longer pause. In these breaks, feel free to put the article down, and rest in whatever your experience of the moment may be.

.

By exploring the energies of addiction in this way, we allow life to move a little bit more freely. We may be surprised at what we learn about ourselves in the process. The goal is not to try and wrestle meaning from this article in order to feel better as an end result but to explore how we can discover a dimension of our experience that is already of peace.

Reframing Addiction

With these suggestions in mind, let’s begin our inquiry. In this section we’ll reconsider what we mean by the term addiction, and explore its presence in our lives as a natural pattern of human life. Let’s ask whether it’s possible that addiction shows up in our lives—or the lives of our friends, family members, or clients—for reasons other than to decimate us and hurt those around us? It’s well known that traumatic events can, in certain circumstance, lead to post traumatic growth. The same is true with addiction.  Although addiction takes lives, relationships, families, hope, and health—the havoc it wreaks might also provide a precious gift to those who are open to receiving it. What if the visible and invisible destruction left in the wake of addiction is fertilizing the soil for new life—similar to the growth that inevitably follows in the aftermath of a forest fire? Besides preparing the soil for new growth, what if the suffering of addiction leaves a seed behind? Through care and attention, that seed can grow into a resilient tree capable of flourishing in the most challenging of life experiences.

Although addiction takes lives, relationships, families, hope, and health—the havoc it wreaks might also provide a precious gift to those who are open to receiving it. What if the visible and invisible destruction left in the wake of addiction is fertilizing the soil for new life—similar to the growth that inevitably follows in the aftermath of a forest fire? Besides preparing the soil for new growth, what if the suffering of addiction leaves a seed behind? Through care and attention, that seed can grow into a resilient tree capable of flourishing in the most challenging of life experiences.  Recent psychological research shows that well-being is a process, not an endpoint, similar to learning how to ride a bike or play a musical instrument. It takes practice and commitment and developing good habits, but it’s also about enjoying the journey and not obsessing on results. Navigating the ups and downs, exploring the side streets, grassy lawns, and back alleys of our lives is part of what makes us human and makes us whole. Recovery from addiction is no different. It, too, is a process. As we explore our addictions to substances and other people, and then press inward to subtler psychological and spiritual terrains, we will usually find at the heart of addiction the same fearful clenching—a habituated and unconscious resistance to what we fear or dislike in this moment. If we are really honest with ourselves, we discover the energy of addiction almost everywhere we look. It is ingrained in some way into almost every aspect of our lives. With this in mind, can you feel safe enough to relax a little around what is okay and what is not okay? Can you be brave enough to stop stigmatizing addiction and relax your labels around what addictive behavior is or isn’t? You can choose to look inside yourself and explore this inquiry anew. What already present qualities and strengths inside can you tap into to help navigate, live with, and perhaps even find beauty in the energy of addiction within you? Although this may initially seem impossible or scary, when you meet what has been labeled addiction in this way, is the word addiction still fitting? In these moments, it may seem more like you are experiencing the mysterious and powerful movement of life energy within you rather than a well-defined, separate, and scary thing called “addiction” or “craving.”

Recent psychological research shows that well-being is a process, not an endpoint, similar to learning how to ride a bike or play a musical instrument. It takes practice and commitment and developing good habits, but it’s also about enjoying the journey and not obsessing on results. Navigating the ups and downs, exploring the side streets, grassy lawns, and back alleys of our lives is part of what makes us human and makes us whole. Recovery from addiction is no different. It, too, is a process. As we explore our addictions to substances and other people, and then press inward to subtler psychological and spiritual terrains, we will usually find at the heart of addiction the same fearful clenching—a habituated and unconscious resistance to what we fear or dislike in this moment. If we are really honest with ourselves, we discover the energy of addiction almost everywhere we look. It is ingrained in some way into almost every aspect of our lives. With this in mind, can you feel safe enough to relax a little around what is okay and what is not okay? Can you be brave enough to stop stigmatizing addiction and relax your labels around what addictive behavior is or isn’t? You can choose to look inside yourself and explore this inquiry anew. What already present qualities and strengths inside can you tap into to help navigate, live with, and perhaps even find beauty in the energy of addiction within you? Although this may initially seem impossible or scary, when you meet what has been labeled addiction in this way, is the word addiction still fitting? In these moments, it may seem more like you are experiencing the mysterious and powerful movement of life energy within you rather than a well-defined, separate, and scary thing called “addiction” or “craving.”

.

The invitation to relax our labels around what addiction is or isn’t is not a call to give up or a statement that the destruction left in the trail of someone who is addicted to heroin is the same, say, as the subtle resistance and self-clinging of a monk. However, the unconscious resistance to life that drives the more overtly destructive forms of addiction is the same unconscious resistance that some contemplative practitioners go into meditation for months at a time to inquire into. It must be asked whether these coarser expressions of resistance provide rare lessons and gifts, even if no one would consciously choose them?  If the root of addiction is resistance to what is, which trails an understandable misunderstanding of who we are and what we need to feel ok, there is nothing more poignant than the agony of addiction to help us see this and wake up to another way of being. In this way, more overt forms of addiction can be potent gifts. They can help us grow and recognize deeper dimensions of meaning and individuality in our lives. The suffering experienced by those of us who have stumbled into addiction’s labyrinth can open us to new possibilities. With love, self-compassion, and self-honesty we can emerge from addictive patterns in better shape than when we first face planted into them.

If the root of addiction is resistance to what is, which trails an understandable misunderstanding of who we are and what we need to feel ok, there is nothing more poignant than the agony of addiction to help us see this and wake up to another way of being. In this way, more overt forms of addiction can be potent gifts. They can help us grow and recognize deeper dimensions of meaning and individuality in our lives. The suffering experienced by those of us who have stumbled into addiction’s labyrinth can open us to new possibilities. With love, self-compassion, and self-honesty we can emerge from addictive patterns in better shape than when we first face planted into them.

What Does Healing From Addiction Really Mean?

Now that we have reframed addiction—and reconsidered its very nature—what does it mean to heal from it? In this section, we’ll explore what “healing” is, and what it’s not. Let’s begin with what it’s not. It’s important to consider how cycles of addiction are perpetuated through our unexamined beliefs about what it means to heal. For example, many of us may consider that healing is an end point or state that we will one day hopefully reach. We might imagine that to be healed means waking up in the morning and feeling good all day long. Nothing ever bothers or hurts us! But in reality, this is neither a helpful nor attainable ideal. And when we are stuck in an addictive pattern and have a skewed perception of healing, we may rightly feel so far away from this ideal of healing that we give up on ourselves, and may believe our situation to be hopeless. Another way we grasp at healing is by conflating it with sobriety, and simply not using – which can unconsciously perpetuate addictive patterns. When we believe that healing is simply not engaging in an overtly destructive behavior, the pendulum swing of addiction moves from a positive to a negative attachment to our addictive vice. When this happens, we remain in suffering, and also miss seeing addiction on a more fundamental level. As we remain stuck in the negative addictive attachment, and thus still in suffering, we may eventually surrender our hope that it is even possible for us to heal. Another common belief that obscures genuine healing is the belief that we’re not worthy of healing. Even if we’re doing all the “right” things, deep down we may feel that we cannot really heal. If we harbor the core belief that we are unworthy of healing, then no matter how well we may succeed at rearranging our life situations, or engaging in healthier behaviors, we’ll still feel deep down that we’re not getting better. This core belief is suffused with the usually unseen, but quite common, addiction to pain. We not only experience addiction to pleasure, but also to pain. The two are often linked, and some forms of chronic pain reflect the body’s physiological attachment to the cycle of pain and its endorphin fueled release. This phenomenon is especially common for people who may have experienced traumatic events in their lives. Naturally, addiction and trauma are often closely linked. In considering the above examples, we see that genuine healing isn’t an end point we reach, isn’t the absence of an overtly destructive behavior, and isn’t something that we can either be worthy or unworthy of. What then, is it?

Now that we have reframed addiction—and reconsidered its very nature—what does it mean to heal from it? In this section, we’ll explore what “healing” is, and what it’s not. Let’s begin with what it’s not. It’s important to consider how cycles of addiction are perpetuated through our unexamined beliefs about what it means to heal. For example, many of us may consider that healing is an end point or state that we will one day hopefully reach. We might imagine that to be healed means waking up in the morning and feeling good all day long. Nothing ever bothers or hurts us! But in reality, this is neither a helpful nor attainable ideal. And when we are stuck in an addictive pattern and have a skewed perception of healing, we may rightly feel so far away from this ideal of healing that we give up on ourselves, and may believe our situation to be hopeless. Another way we grasp at healing is by conflating it with sobriety, and simply not using – which can unconsciously perpetuate addictive patterns. When we believe that healing is simply not engaging in an overtly destructive behavior, the pendulum swing of addiction moves from a positive to a negative attachment to our addictive vice. When this happens, we remain in suffering, and also miss seeing addiction on a more fundamental level. As we remain stuck in the negative addictive attachment, and thus still in suffering, we may eventually surrender our hope that it is even possible for us to heal. Another common belief that obscures genuine healing is the belief that we’re not worthy of healing. Even if we’re doing all the “right” things, deep down we may feel that we cannot really heal. If we harbor the core belief that we are unworthy of healing, then no matter how well we may succeed at rearranging our life situations, or engaging in healthier behaviors, we’ll still feel deep down that we’re not getting better. This core belief is suffused with the usually unseen, but quite common, addiction to pain. We not only experience addiction to pleasure, but also to pain. The two are often linked, and some forms of chronic pain reflect the body’s physiological attachment to the cycle of pain and its endorphin fueled release. This phenomenon is especially common for people who may have experienced traumatic events in their lives. Naturally, addiction and trauma are often closely linked. In considering the above examples, we see that genuine healing isn’t an end point we reach, isn’t the absence of an overtly destructive behavior, and isn’t something that we can either be worthy or unworthy of. What then, is it?

.

Can we reassess what healing actually means for ourselves? This can be a scary question. However, a deep and honest inquiry can reveal so much. You have a unique experience of healing, and so there is no need to look outward or compare yourself to others. When we consider that our efforts to heal matter so much and yet there is so much that we don’t have control over, we allow ourselves to relax more. We find that we don’t need to take ourselves so seriously. We may also find that our resolution to recover is empowered in a way that it can never be while we are fearfully hanging on and trying to manage every aspect of our inner and outer lives in order to “heal”. When we see that we don’t know what will come tomorrow, or if tomorrow will come at all, we open to the possibility of wonder, humility, and the willingness to look anew. We open to the direct experience of healing, health, and well-being.

Can we reassess what healing actually means for ourselves? This can be a scary question. However, a deep and honest inquiry can reveal so much. You have a unique experience of healing, and so there is no need to look outward or compare yourself to others. When we consider that our efforts to heal matter so much and yet there is so much that we don’t have control over, we allow ourselves to relax more. We find that we don’t need to take ourselves so seriously. We may also find that our resolution to recover is empowered in a way that it can never be while we are fearfully hanging on and trying to manage every aspect of our inner and outer lives in order to “heal”. When we see that we don’t know what will come tomorrow, or if tomorrow will come at all, we open to the possibility of wonder, humility, and the willingness to look anew. We open to the direct experience of healing, health, and well-being.

.

What does this insight tell us about healing? Often, we hear that we need to hit rock bottom in order to heal. We hear that we do a disservice to ourselves, or to the one struggling with addiction, by preventing this bottoming out. However, does this really mean we need to let everything fall apart before we can start to heal and climb out of the pit we have dug ourselves into? What if hitting bottom points more to an attitude than a fixed event? What if healing was more of an innate quality of our awareness than a fixed state that we achieve? One aspect of this healing quality of awareness is that it can see how we are in control in certain ways and yet not at all in even more ways—that we are changing and growing processes.  Our contact with this healing quality of awareness seems to come about through a certain kind of dying. When we hit bottom (which does not need to be a literal bottom), we realize that all of our strategies, attempts, and maneuvers to not hurt so much have failed miserably. With this recognition, you may feel that you are submerged and swimming in emotion. You may find yourself struggling to breathe but at the same time watching everything simply unfold—looking sometimes like a movie and sometimes like a train wreck. You realize in these moments that although you are at the bottom of the barrel, it is just where you belong. You realize that there isn’t much to do besides simply see and be there totally.

Our contact with this healing quality of awareness seems to come about through a certain kind of dying. When we hit bottom (which does not need to be a literal bottom), we realize that all of our strategies, attempts, and maneuvers to not hurt so much have failed miserably. With this recognition, you may feel that you are submerged and swimming in emotion. You may find yourself struggling to breathe but at the same time watching everything simply unfold—looking sometimes like a movie and sometimes like a train wreck. You realize in these moments that although you are at the bottom of the barrel, it is just where you belong. You realize that there isn’t much to do besides simply see and be there totally.  To be totally out of options. Perhaps the most sincere place one can ever be. From this place strength emerges. From this place, we may begin to act and make decisions that are not wholly based on escaping this moment. We may realize there is nothing we can ever escape, and that the kindest thing we can do for ourselves is to simply be here with and in whatever arises. This is a humbling process. This is the process and experience of healing. Through finally meeting our inner experiences with honesty and love, we may notice a sense of ourselves that is deeper than any story, emotion, or thought that we may be having. We may notice whether the part that has let go has opened up space for recognizing what has always been here. And once opened, the connection with the presence of this moment, a deeper aspect of who we are, always remains. It is this aspect of ourselves that is innately healing. When we are in touch with this quality of awareness, we can see that even difficulty, shame, fear, and guilt are alright. This means that healing is not dependent on the absence of craving or difficulty. In fact, it is the only place where we can be genuinely intimate with craving and difficulty. This is one of the gifts of addiction. To continue living, addiction pushes us to a point where we have no other option than to consciously connect with the life currents of healing and wellness within ourselves. When you are connected with the healing qualities of awareness, you are also connected with presence—the essence of this present moment—and you may realize that this is the only space that healing can ever occur and also the only place where—in a way—you feel already healed and at peace by simply being.

To be totally out of options. Perhaps the most sincere place one can ever be. From this place strength emerges. From this place, we may begin to act and make decisions that are not wholly based on escaping this moment. We may realize there is nothing we can ever escape, and that the kindest thing we can do for ourselves is to simply be here with and in whatever arises. This is a humbling process. This is the process and experience of healing. Through finally meeting our inner experiences with honesty and love, we may notice a sense of ourselves that is deeper than any story, emotion, or thought that we may be having. We may notice whether the part that has let go has opened up space for recognizing what has always been here. And once opened, the connection with the presence of this moment, a deeper aspect of who we are, always remains. It is this aspect of ourselves that is innately healing. When we are in touch with this quality of awareness, we can see that even difficulty, shame, fear, and guilt are alright. This means that healing is not dependent on the absence of craving or difficulty. In fact, it is the only place where we can be genuinely intimate with craving and difficulty. This is one of the gifts of addiction. To continue living, addiction pushes us to a point where we have no other option than to consciously connect with the life currents of healing and wellness within ourselves. When you are connected with the healing qualities of awareness, you are also connected with presence—the essence of this present moment—and you may realize that this is the only space that healing can ever occur and also the only place where—in a way—you feel already healed and at peace by simply being.

.

Our intentions and actions matter so much. This is evident in how children respond to their parents’ efforts to be kinder, and more nourishing. Yet at the same time, we are just one small part of life that has very little control over our outcomes. We are just one part and process of a larger collection of energetic processes that we are held within.

Do you make your heart beat?

Do you move the breath in and out of your body?

Thank goodness we are not in control of everything. How limiting the experience of life would be if we needed to consciously beat our heart. Could we even do it? A friend once said to me, “With our attention spans, we would probably forget or get distracted, and that would be the end of it!” What a mystery this process of life is! If we look outside ourselves, we see that the processes of healing and growth are intimately intertwined with the processes of destruction. Could it be any other way inside this human body and mind? Aren’t we connected to life in the same way that a plant is? Destruction often clears the way for something new to emerge. New seedlings grow from the rot of dead and decaying, once majestic and kingly trees. Let us not be too hasty to judge our “failures” and “setbacks,” for we don’t know what fertilizer they might serve as for some new seed of wellness. In fact, we can be certain that in the wake of destruction, new life will grow. We just don’t know how, when, or what form our own life trajectories will take. With this in mind, is it possible to simply enjoy the processes of life and death that we are intertwined with, and connect the best we can with the unique currents of healing and wellness within us?

The Heart of Addiction and its Recovery

Addiction—as unseen resistance to what is—is always connected with this moment and everything happening in it. It disappears just as soon as it emerges. It is always speaking in new, never before heard words. Recovery from addiction is about opening to the wonder of this very moment. When we are present to the energy of addiction in this way, we may make a great discovery. We may discover that the natural life energy of addiction is inseparable from our own life energy—which may be felt as wonder and a sense of aliveness. In this way, as addiction is seen to be a natural, unconscious process of resistance, recovery is seen to be a process as well. Recovery is revealed as a loving, moment-by-moment, embrace of resistance. We do not need to wait years to feel better. Health, healing, and the peace we yearn for are in large part the life-blood of this moment. This is true even if craving and discomfort are present.

Addiction—as unseen resistance to what is—is always connected with this moment and everything happening in it. It disappears just as soon as it emerges. It is always speaking in new, never before heard words. Recovery from addiction is about opening to the wonder of this very moment. When we are present to the energy of addiction in this way, we may make a great discovery. We may discover that the natural life energy of addiction is inseparable from our own life energy—which may be felt as wonder and a sense of aliveness. In this way, as addiction is seen to be a natural, unconscious process of resistance, recovery is seen to be a process as well. Recovery is revealed as a loving, moment-by-moment, embrace of resistance. We do not need to wait years to feel better. Health, healing, and the peace we yearn for are in large part the life-blood of this moment. This is true even if craving and discomfort are present.  Awakening to the presence of resistance in this way does not mean that resistance will necessarily disappear. This is particularly important to contemplate if your inquiry into addiction reaches outwards to include social expressions of addiction. When we inquire into social expressions of addiction such as racism, patriarchy, hyper consumerism, etc., the resistance of the pattern does not dissipate at the same rate as our more individual addictions. There is a lot of momentum to social and collective addictive patterns. However, whether we are encountering individual or social forms of addiction, the momentum of these patterns of resistance does not obscure our felt connection with the qualities of healing and peace within. In the moment that you become viscerally aware of resistance as an experience of habitual clenching rather than as the basis of who you are, you also see that resistance is not a problem. You transform addiction by seeing that it is a natural pattern of life. The moment this is seen, the emergence of addictive energy no longer divides you or your life into separate things. While distinctions of course still remain, when this moment is not being divided into essentially separate pieces, is there anything really that requires numbing? Through moment-by-moment living inquiry into addiction, you realize who you are on a more fundamental level. In doing so, you also play an important role in disrupting individual and social patterns of addiction. At the same time, you feel connected with the peace of presence, even if certain aspects of your life situation still carry the residue, momentum, and discomfort of old patterns of tension and pain.

Awakening to the presence of resistance in this way does not mean that resistance will necessarily disappear. This is particularly important to contemplate if your inquiry into addiction reaches outwards to include social expressions of addiction. When we inquire into social expressions of addiction such as racism, patriarchy, hyper consumerism, etc., the resistance of the pattern does not dissipate at the same rate as our more individual addictions. There is a lot of momentum to social and collective addictive patterns. However, whether we are encountering individual or social forms of addiction, the momentum of these patterns of resistance does not obscure our felt connection with the qualities of healing and peace within. In the moment that you become viscerally aware of resistance as an experience of habitual clenching rather than as the basis of who you are, you also see that resistance is not a problem. You transform addiction by seeing that it is a natural pattern of life. The moment this is seen, the emergence of addictive energy no longer divides you or your life into separate things. While distinctions of course still remain, when this moment is not being divided into essentially separate pieces, is there anything really that requires numbing? Through moment-by-moment living inquiry into addiction, you realize who you are on a more fundamental level. In doing so, you also play an important role in disrupting individual and social patterns of addiction. At the same time, you feel connected with the peace of presence, even if certain aspects of your life situation still carry the residue, momentum, and discomfort of old patterns of tension and pain.

.

Let us continue to explore what our addictions are asking for. What are they pointing to? What have we disowned about ourselves that is asking to be seen? Let’s see if we can remain interested in discovering what healing looks like for us in this moment… and in this one. This process may be challenging, but know that it is a homecoming, and a process of growth. Yet, paradoxically, it is also about recognizing within you that which does not require growth. This full-blooded embodied intimacy with addiction and its healing is sacred. Can you dare to approach it with the attitude of reverence that it deserves?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Victor Bucklew, PhD is a counselor-in-training, scientist, Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction facilitator, environmental activist, and person in long-term recovery from addiction. He received his PhD in Laser Physics from Cornell University, and currently researches the quantum mechanics of light. He is author of the three-time award winning book, The Hidden Gifts of Addiction: The Direct Path of Recovery. For more, please visit www.victorbucklew.com.

Victor Bucklew, PhD is a counselor-in-training, scientist, Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction facilitator, environmental activist, and person in long-term recovery from addiction. He received his PhD in Laser Physics from Cornell University, and currently researches the quantum mechanics of light. He is author of the three-time award winning book, The Hidden Gifts of Addiction: The Direct Path of Recovery. For more, please visit www.victorbucklew.com.

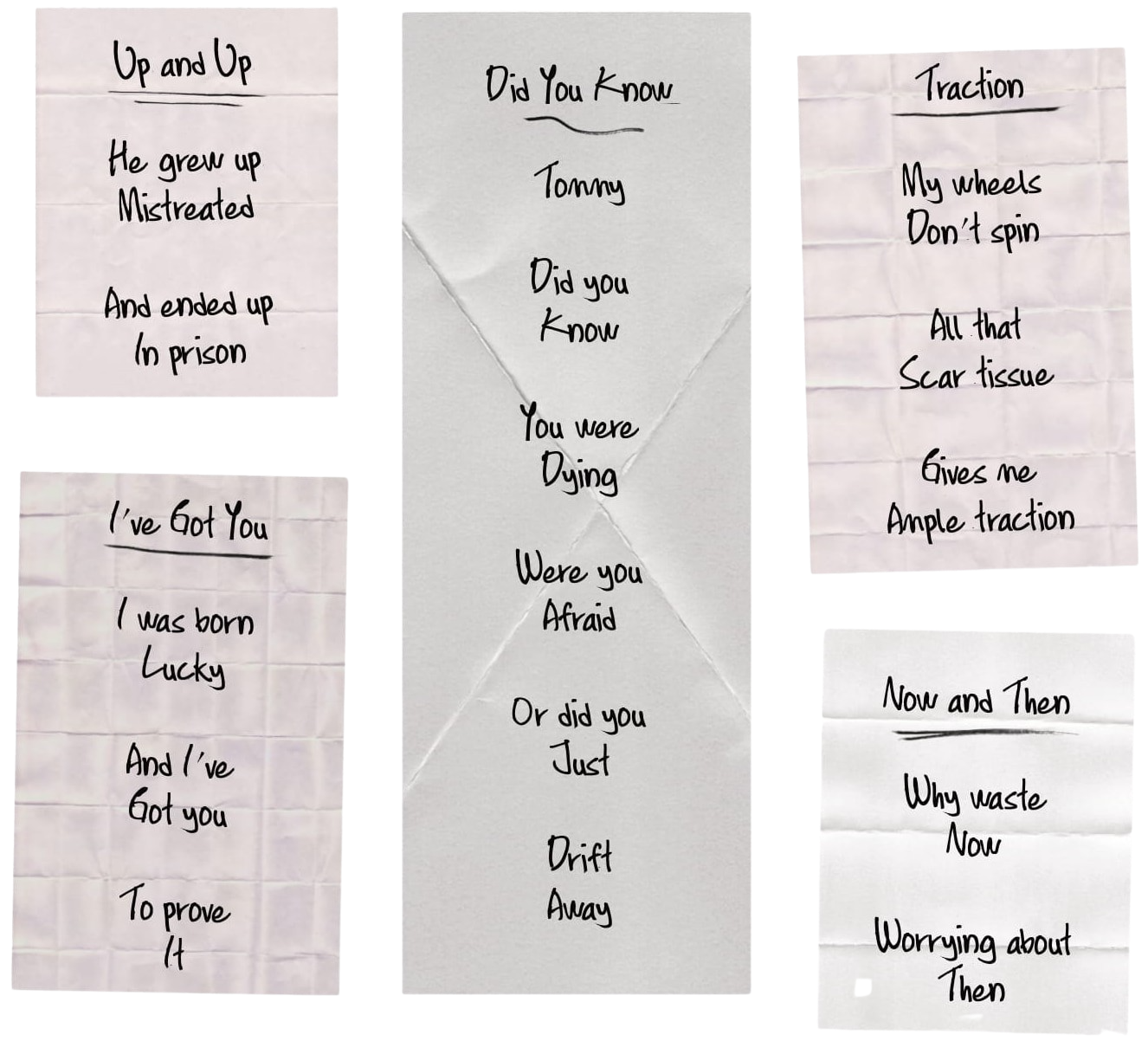

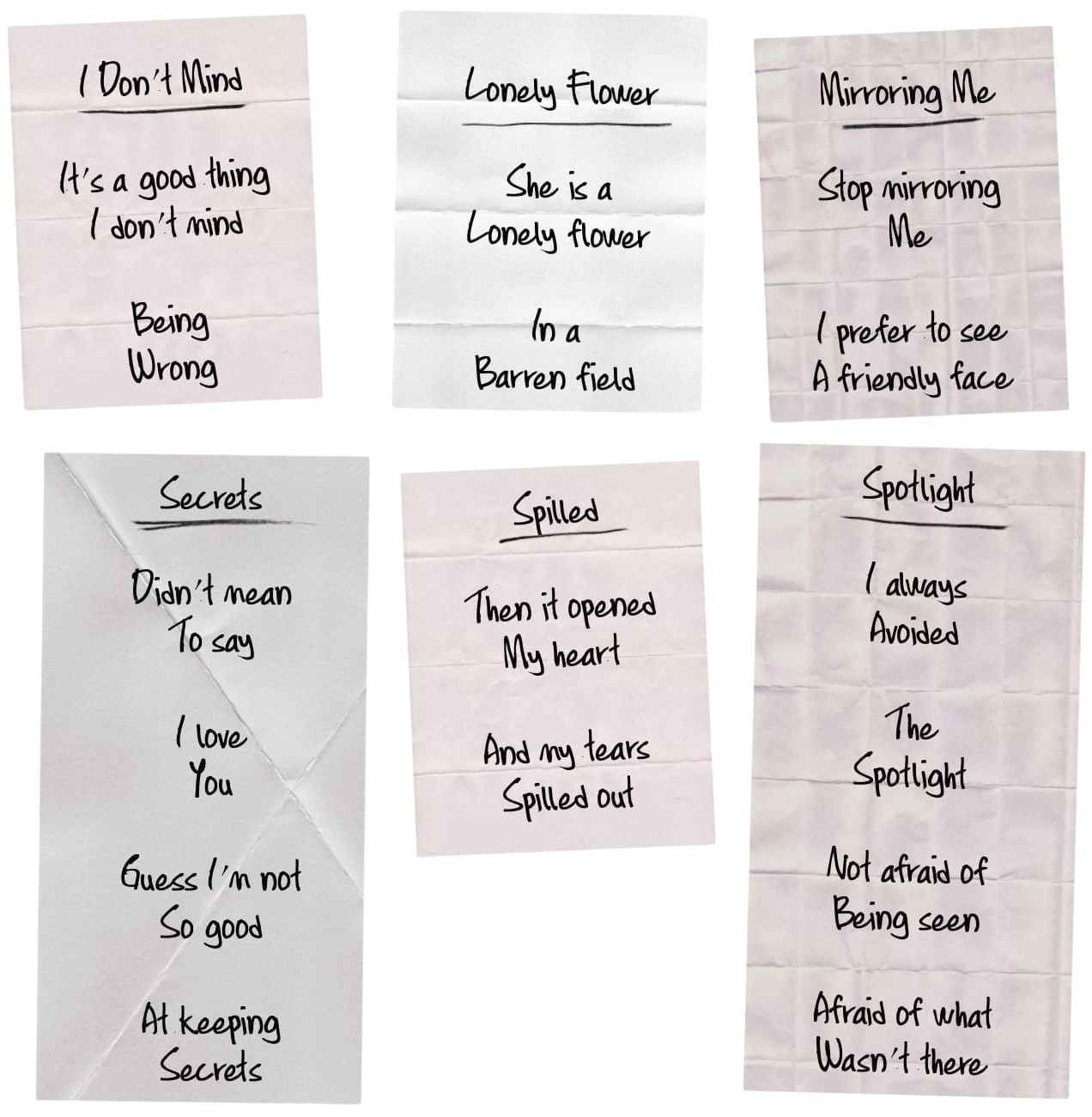

Writing on Napkins

A poetry collection from Tom Bowlin, 2021

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tom Bowlin writes about what life is like for us, what's been done to us, what we do to each other, and what we just think sometimes. Tom lost his son at an early age and many of his poems are about loss and the hard times we all experience. His poems don't always reflect his personal beliefs, instead he views them as short stories about "us." His 2 poetry books are Us and Love and Loss.

Tom Bowlin writes about what life is like for us, what's been done to us, what we do to each other, and what we just think sometimes. Tom lost his son at an early age and many of his poems are about loss and the hard times we all experience. His poems don't always reflect his personal beliefs, instead he views them as short stories about "us." His 2 poetry books are Us and Love and Loss.

Illness as a Dharma Door

© 2021 Susan M. Pollak, MTS, EdD

On a dark and frigid day in February 2020, we found out that my husband had a rare and deadly blood cancer. It could be treated but not cured. It was difficult to diagnose, and we initially thought it was just back pain. Everyone in mid-life has back pain, right? However, an MRI showed this was no usual pain—over ten bones in his spine had fractured due to the cancer, causing excruciating pain.

While there was a new procedure that could help, treating one fracture at a time over a period of months, Covid-19 had swept through the world, overwhelming the hospitals. Even in a city overflowing with medical care, this cancer treatment was suddenly not “essential.” We would need to wait and endure.

While there was a new procedure that could help, treating one fracture at a time over a period of months, Covid-19 had swept through the world, overwhelming the hospitals. Even in a city overflowing with medical care, this cancer treatment was suddenly not “essential.” We would need to wait and endure.

As support from family and friends dwindled due to Covid—no food, no hugs, no visits--like so many others I began to feel alone and overwhelmed. I had a steady meditation practice that sustained me over the years, but I longed for more. I wasn’t sleeping and I was feeling disoriented. I dreamed of finding a meditation master who understood the ravages of plagues, as impossible as that sounds.

An email arrived in my inbox from New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care announcing a deep dive into the writing of Eihei Dogen, a 13th century Zen Master, and the founder of Japanese Soto Zen. The class, called “Use All the Ingredients of Your Life” was taught by Zen teacher Koshin Paley Ellison. I’d always felt an affinity for Dogen, first learning about his teaching on “the backward step” from Trudy Goodman, founder of Insight LA. This teaching, which in essence is about stepping back from the chaos of daily life, had always given me a sense of relief and perspective, like the comfort of a wise elder. Dogen had lived through a plague. Could this class help? A line from W.H..Auden’s poem, Musee Des Beaux Arts, popped into my head, “About suffering they were never wrong, The old Masters.”

The irony of pushing the “Register” button on the computer screen didn’t escape me. But I did wonder, what could a medieval Zen monk impart as I tried to navigate this mind-boggling and dangerous maze of high-tech chemotherapy, skyscraper hospitals, and the medical complexity of a stem cell transplant?

Start Where You Are

The main text was the classic Tenzo Kyokun, “Instructions for the Zen Cook.” Being skeptical, I doubted how an instruction manual written in 1237 for male monastics was going to help a woman with two children and a seriously ill husband. But as I read with an open and somewhat desperate mind, I became intrigued both by how practical and grounded Dogen’s instructions were.

Because of Covid, I’d been cooking every meal from scratch: no restaurants, no take-out, no shopping or kitchen help. I was numb and exhausted. Without realizing it, I’d stopped really seeing the food, tasting it, or appreciating it. Just getting through the day was an accomplishment. Everything felt like a burden. A line in the text spoke gently to me: “Handle even a single leaf or green in such a way that it manifests the body of the Buddha. This in turn allows the Buddha to manifest through the leaf,” (p. 7).

That evening, as I juiced a lime, I marveled at the exquisite green of the skin and the sharp fragrance of the fruit. As I followed the instructions in a recipe for chopping lemongrass, there seemed to be deeper meaning: “Peel off the layers until smooth and tender. Cut off the tough, thick base.” I interpreted this as guidance on how to work skillfully with the hard, brittle defenses I had constructed to muscle through this fraught and anxious time. Maybe I could uncover the soft and vulnerable parts of my being that needed to be seen, heard and nourished. The tender ivory lemongrass glowed in the autumn light as I chopped. I paused. I breathed. I was seeing and smelling again. At least for that night, Dogen’s “Joyful Mind” permeated the previously tedious task of making dinner.

A Brilliant Developmental Psychologist

We often speak of the Buddha as the first Psychologist because of his insights into the nature of the mind. I’ve begun to think of Dogen as the first “Developmental Psychologist” because of his understanding of what “ingredients” we need to grow and mature. As someone who was trained both as a Clinical and Developmental Psychologist, I appreciated Dogen’s attention to our deep basic needs and guidance on how to work with them. As those who have raised children know, an infant needs almost constant feeding and care. With Dogen’s intuitive focus on caring and paying attention to food, and the importance of feeding each other and the community, he speaks to and attends to our deep and unmet hungers and need for nourishment. It is done in such a subtle and skillful way you could miss it. Most monks, of course, do not talk about parenting. Yet Dogen explicates the importance of having the mind and heart of a parent, or Roshin.

As I began to live these passages, I began to realize that Dogen was helping us reparent ourselves through zazen (or sitting meditation) so we can develop the resilience and spirt to handle the challenges of every aspect of life. We learn how to care for ourselves with love, and how to tend to and care for others, developing the affectionate concern that a parent has toward a child. “Zazen restores our vision”, (p.35) Dogen (2005) tells us. Step by step, grain of rice by grain of rice, we are given the skills to begin to “cook” or manage our personal lives. It is like being given a very practical toolbox, or perhaps I should say, a more functional set of cooking implements. Zen teacher and writer Edward Espe Brown (2019) puts it eloquently, noting that with Dogen’s collection of sound advice, [W]e can grow wise and compassionate rather than simply older, (p. xiv).

As I began to settle into the new but unwanted circumstances of my life, I stopped fighting so hard. Brown’s (2019) deep understanding of Dogen’s teaching provided further wisdom. “We cannot control what comes our way, so we find out how to work with what comes: ingredients, body, mind, feelings, thoughts, time…” (xv).

I began to realize that this text was in fact a training of mind and heart. I thought of Jane Hirshfield’s poem “A Cedary Fragrance” where she writes about her years of study at the Tassajara Zen Center, and how, years later, she still chooses to wash her face with cold water:

It felt like a path of learning to “co-habit” with serious illness began to open for me.

The Biggest Delusion

About thirty years ago, I attended a public lecture given by the meditation teacher Joseph Goldstein. Although I was young and was still in school, his words were arresting: “The biggest delusion we have,” Joseph said, “is that we won’t age, we won’t grow ill, and we won’t die.” I have not forgotten the wisdom of this message.

It is three am. I wake in panic. “Things are very wrong” is my first thought. My body is stiff. I am fully awake. There is no way that I’ll get back to sleep. I’m getting to know insomnia. I attempt to work with the fear. I try a Dogen-inspired cognitive reframe (a term psychologists use to describe ways of working with an unruly mind) to see if I can soothe myself. “Hmmm,” I try, being creative. “What if you don’t like this ingredient?” I pause. Something stirs within. “Yes, I don’t like this. I don’t like the taste of cancer. It is bitter. It is scary. It is painful.” There is something in the cadence of the words that reminds me of Dr. Seuss, “I do not like Green Eggs and Ham. I do not like them Sam I Am.” I realize that I’m having a bit of a tantrum. I don’t want my husband to be seriously ill. I do not want this suffering. I don’t like it. I didn’t choose this. But I don’t have a choice.

I have to smile at the conjunction of Dogen and Dr. Seuss, wondering if these two writers might enjoy each other. I begin to imagine a fantasy dinner party with the two men as guests. What would I serve? Surely Dogen is a vegan? The metaphor of cooking your life goes more deeply than I imagined. As Koshin reflected, “What is not food?” Soothed by this wisdom, and a touch of whimsy, I fall back asleep.

Using All the Ingredients

There is a Zen story where the teacher asks a student to clean up the garden. The overzealous student picks up leaves, weeds, stones, and moss and puts them in a pile of waste. The teacher then carefully sorts through the “trash,” picking out the stones to use for drainage, the weeds for compost, and the moss to retain moisture around delicate and fragile plants. There is a place and a use for everything.

I begin to reflect on what hidden treasures I can find in what feels like, as the Buddhists call it, a “hell realm.” Are there ingredients I could excavate from this chaotic mess? Could my heart open more to the suffering of others? Could I find more patience? More compassion? Deeper resilience? What if everything belongs, including illness, aging and death.

I think of the radical way Monet used color in his landscapes. At first, the splash of bright orange poppies seems discordant, but it isn’t. It wakes the eye up. “Keep your eyes open,” Dogen instructs us.

You Will Get Everything

Trudy Goodman, founder of Insight LA, tells a story about Seung Sahn, a Korean Zen Master. “If you embark on this path, you will get everything” he promised his students. And having a mind that wanted more, she was overjoyed. “Wow, I’ll get everything,” she smiled with anticipation.

However, many decades and much suffering later, she realized what he meant. “Oh, I’ll get EVERYTHING.”

As I reflect on Dogen, I realize that he is talking about how to care for Everything—food, cooking, our bodies, kitchen utensils, tea bowls, relationships, work. He gently instructs us on how to make space for all the ingredients in life. Every detail is addressed. In his instructions in How to Cook Your Life he helps us wake up to the truth of impermanence, “like the dewdrop on a blade of grass along the path that vanishes quickly, who knows when this life will end,” (2005, p. 62). Yet what is so skillful is that first he grounds us in the reality, and joy, of daily life. It reminds me of what psychological theorists call “stage theory.”

As I reflect on Dogen, I realize that he is talking about how to care for Everything—food, cooking, our bodies, kitchen utensils, tea bowls, relationships, work. He gently instructs us on how to make space for all the ingredients in life. Every detail is addressed. In his instructions in How to Cook Your Life he helps us wake up to the truth of impermanence, “like the dewdrop on a blade of grass along the path that vanishes quickly, who knows when this life will end,” (2005, p. 62). Yet what is so skillful is that first he grounds us in the reality, and joy, of daily life. It reminds me of what psychological theorists call “stage theory.”

And this is the loving guidance that I need. The statistics for life expectancy with my husband’s cancer are not good, and I try not to dwell on an abstract number, but to focus on living fully in the present. This gentle, kind, but firm writing is refreshing. So many family, friends and colleagues say to me, “Be positive, you have to be positive!” as if this can alter the course of an illness. And when there isn’t a cure, the aftermath is often a sense of guilt. Did I not try hard enough? Was I not positive enough? Why set yourself up for more anguish or shame?

This World of Dew

About a year ago, I registered for a retreat at the Cambridge Insight Meditation Center on the day of the winter solstice. Who know, in December of 2019, how 2020 would unfold?

It was a cold, dark and miserable day, with a wet and heavy New England snow, the kind that clings to the trees and we call “heart attack snow.” The meditation hall was overheated so I practiced walking meditation outside in the snow. I walked by a birch tree that was weighed down with the snow. The first two times I passed it I didn’t really see it. But on the final walk of the retreat, after hours of sitting and walking, it had changed. I had changed. The branch was filled with raindrops, each glistening with radiant light, as if each contained a moon. I gasped. Before, all I had seen was the gloom.

I thought of a classic haiku by the poet Issa, written in the throes of grief after the death of his child. While there are many translations, my favorite is from writer Pico Iyer, who called it a “gasp” of a poem. “This world of dew is a world of dew, and yet, and yet…”

Now, a year later, I think of this as a koan (often called a “Zen riddle”) for my life. If I really pay attention, stop, listen and see deeply, what can I discover alongside the darkness and the grief?

“Our body is impermanent…”

As I write, my husband is in the ICU, where he will be for over two weeks undergoing a stem cell transplant to help keep him alive and hopefully put his cancer in remission. An infusion of chemotherapy will wipe out his bone marrow and cancerous cells, often causing a daunting array of side effects. “Our body is impermanent, our time difficult to hold on to,” (1996, p. 111). How to be with this, how to “settle” as Dogen would say? How to bear witness to a loved one who is seriously ill and still stay grounded and equanimous? This is the task that so many of us are faced with during Covid, as we watch dear friends, colleagues and family become ill and die. This is now our shared reality. As Dogen puts it we are all like “a fish in a dwindling pool of water,” (1996, p 111). Like it or not, this is the human condition, and each breath, he counsels, may be our last.

Dogen does not sugar coat anything, from food, to ethical behavior in difficult relationships, to the impermanence of life. Edward Espe Brown, who was the Tenzo (head chef) at Tassajara Zen Center, addresses this directly, “Why don’t you taste the true nature of each moment instead of trying to make everything taste just the way you want it to?… What, did you think you could add milk and sugar to each moment of your life to make it taste the way you want?” (2019, p. 13). Certainly food for thought.

As Brown points out, the deeply resonant words of Dogen, when taken to heart, help us see deeply into the nature of things. They teach us how to work with what we have, not what we want.

When I started reading Dogen, I was attempting to curate and conceptualize grief. As I look back, although I would have denied it, I wanted to get rid of grief, illness and death, not drop into it and get to really know it.

I have taken liberties with Hafiz’s poem, “My Eyes So Soft.”

To conclude, I’m learning to sit in the midst of what the Buddhists call “heavenly messengers”—illness, old age, and death. The teaching is that these messengers are here to wake us up, not to turn away, but to be moved by all the ingredients of life. And this, as Dogen shows us, is the way of growing in wisdom, compassion and peace—no matter what arises.

References

Brown, E. 2019. The Most Important Point. Boulder: Sounds True.

Hafiz. 1999. The Gift. (translated by Daniel Ladinsky), cited in Brown, (2019, p. 166).

Leighton, T. D. & Okamura, S. trans. 1996. Dogen’s Pure Standards for the Zen Community. New York: State University of New York Press.

Uchiyama, Kosho. 2005. How to Cook Your Life: From the Zen Kitchen to Enlightenment. Boulder: Shambhala.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Susan M. Pollak, MTS, EdD, is a psychologist in private practice in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She is a longtime student of meditation and yoga who has been integrating the practices of meditation into psychotherapy since the 1980s. Dr. Pollak is cofounder and teacher at the Center for Mindfulness and Compassion at Harvard Medical School/ Cambridge Health Alliance and president of the Institute for Meditation and Psychotherapy. Dr. Pollak is a co-editor of The Cultural Transition; and a contributing author of Mapping the Moral Domain; Evocative Objects; and Mindfulness and Psychotherapy, 2nd Edition. She is the coauthor of Sitting Together: Essential Skills for Mindfulness-Based Psychotherapy and the author of the new book, Self-Compassion for Parents: Nurture Your Child by Caring for Yourself. She writes the popular blog, The Art of Now for Psychology Today, and is a frequent contributor to the Ten Percent Happier App. https://www.drsusanpollak.com/.

Susan M. Pollak, MTS, EdD, is a psychologist in private practice in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She is a longtime student of meditation and yoga who has been integrating the practices of meditation into psychotherapy since the 1980s. Dr. Pollak is cofounder and teacher at the Center for Mindfulness and Compassion at Harvard Medical School/ Cambridge Health Alliance and president of the Institute for Meditation and Psychotherapy. Dr. Pollak is a co-editor of The Cultural Transition; and a contributing author of Mapping the Moral Domain; Evocative Objects; and Mindfulness and Psychotherapy, 2nd Edition. She is the coauthor of Sitting Together: Essential Skills for Mindfulness-Based Psychotherapy and the author of the new book, Self-Compassion for Parents: Nurture Your Child by Caring for Yourself. She writes the popular blog, The Art of Now for Psychology Today, and is a frequent contributor to the Ten Percent Happier App. https://www.drsusanpollak.com/.

The Wound of Today

© 2021 Radhule Weininger, PhD

When I reflect on our community, our country, and our world right now, I feel uncertain. On the one hand, our government seems more stable, vaccines are rolling out, and kids will now return to school. On the other hand, it is as if a partly hidden ogre is slowly crawling towards us, underground. The beast has not broken completely through the surface, but we can see some spikes and some puffs of smoke rolling in our direction. Conversations with my old friends from Germany, the Netherlands, and Portugal, confirmed that they harbored similar feelings. In Germany and the Netherlands there are street fights between right and left, and painful stories of conspiracy and treachery are being thrown about, especially on social media. And nowadays, with the availability of linkedin messaging automation, everyone can be easily connected from various parts of the globe under a single roof.  I asked my physician husband, Michael, how we might understand what’s happening as if it was an ailment in the body (medical metaphors often help me to see more clearly the origin and progress of painful dynamics). He equated the global political unrest to a deep fissure, a wide gaping gash, like a wound that has not really healed. Even though there is a Band-Aid or dressing covering the wound, it seems so deep that it needs more than a superficial fix, and has now become infected. Michael continued with his metaphor, describing two types of healing where wounds are concerned: healing by primary and healing by secondary intention. Wounds that heal by primary intention have edges that are close together and smooth. These wounds can be sutured easily. Wounds that heal by secondary intention, have jagged edges that are far apart and may contain dirt inside.

I asked my physician husband, Michael, how we might understand what’s happening as if it was an ailment in the body (medical metaphors often help me to see more clearly the origin and progress of painful dynamics). He equated the global political unrest to a deep fissure, a wide gaping gash, like a wound that has not really healed. Even though there is a Band-Aid or dressing covering the wound, it seems so deep that it needs more than a superficial fix, and has now become infected. Michael continued with his metaphor, describing two types of healing where wounds are concerned: healing by primary and healing by secondary intention. Wounds that heal by primary intention have edges that are close together and smooth. These wounds can be sutured easily. Wounds that heal by secondary intention, have jagged edges that are far apart and may contain dirt inside.  When I reflected on this, I thought that, in the case of our society, the different political, cultural, social, and racial camps are enormously far apart - so far that they can’t listen to or hear each other. Many from one camp despise those from the other, and there is certainly dirt and infection in those wounds. Michael continued his metaphor by saying that in wounds that heal by secondary intention, healing has to occur slowly and from the bottom up. And, after the wound has been cleaned, there are 4 stages of healing: hemostasis, when bleeding ceases, inflammation, where old toxins and cell debris are carried away, proliferation, which is the process of gradually filling in the wound with granulation tissue FROM THE BOTTOM UP, and finally, there is remodeling where the inflammatory response goes away and contraction can occur. In the end, a scar remains, and with that a new state of homeostasis and stability. He ended by explaining that we have to keep this gaping wound clean and allow it to gradually cycle through the different stages of healing. When we do, healing arises from the depth of the wound, organically, all by itself. The body knows how to heal itself and does so when the conditions are right. We might be under the illusion that the wounds we see – polarization, racism, environmental destruction, greed, and inequality to name but a few – are easy to fix, like wounds that can be healed by primary intention as if the recent election could be a suturing that will bring both sides together. Sadly, this is not the case. For this gaping, infected wound, there is no quick fix. However, the metaphor of healing from the bottom up applies here. If and when the conditions are right, then we can trust that the deep natural healing process of our greater body, a process that happens from the ground up, will occur.

When I reflected on this, I thought that, in the case of our society, the different political, cultural, social, and racial camps are enormously far apart - so far that they can’t listen to or hear each other. Many from one camp despise those from the other, and there is certainly dirt and infection in those wounds. Michael continued his metaphor by saying that in wounds that heal by secondary intention, healing has to occur slowly and from the bottom up. And, after the wound has been cleaned, there are 4 stages of healing: hemostasis, when bleeding ceases, inflammation, where old toxins and cell debris are carried away, proliferation, which is the process of gradually filling in the wound with granulation tissue FROM THE BOTTOM UP, and finally, there is remodeling where the inflammatory response goes away and contraction can occur. In the end, a scar remains, and with that a new state of homeostasis and stability. He ended by explaining that we have to keep this gaping wound clean and allow it to gradually cycle through the different stages of healing. When we do, healing arises from the depth of the wound, organically, all by itself. The body knows how to heal itself and does so when the conditions are right. We might be under the illusion that the wounds we see – polarization, racism, environmental destruction, greed, and inequality to name but a few – are easy to fix, like wounds that can be healed by primary intention as if the recent election could be a suturing that will bring both sides together. Sadly, this is not the case. For this gaping, infected wound, there is no quick fix. However, the metaphor of healing from the bottom up applies here. If and when the conditions are right, then we can trust that the deep natural healing process of our greater body, a process that happens from the ground up, will occur.  We need to ask ourselves, what can we do to facilitate the healing of this gaping wound in our society. First, we have to realize the precarious state of the wound and that we all have to work together to create conditions that will facilitate healing. Our practices of mindful and loving awareness, compassion, and forgiveness are the necessary complement to active listening and engagement with the other. An inner change of attitude allows us to overcome emotional inflammation, tribalism and to realize that we share the same common humanity, and the great body of this living planet. When we drop into our heart-mind we arrive in this place of healing. We need practices that bring us to our shared humanity, our shared relatedness as planet-beings. Then we can come into the ground that holds us all, the loving awareness that is primordially there. We need an act of faith to trust that our love is stronger than our hate. When we find this deeper common ground as humans, as well as our shared interdependence as spiritual beings, then we will find a sense of shared meaning and purpose and our greatest yearning will be for the welfare and wellness of the whole. When we come into that shared intention, we will realize that our wellness and the wellness of others is totally interdependent and necessary to sustain the lives of our children and the life of our world.

We need to ask ourselves, what can we do to facilitate the healing of this gaping wound in our society. First, we have to realize the precarious state of the wound and that we all have to work together to create conditions that will facilitate healing. Our practices of mindful and loving awareness, compassion, and forgiveness are the necessary complement to active listening and engagement with the other. An inner change of attitude allows us to overcome emotional inflammation, tribalism and to realize that we share the same common humanity, and the great body of this living planet. When we drop into our heart-mind we arrive in this place of healing. We need practices that bring us to our shared humanity, our shared relatedness as planet-beings. Then we can come into the ground that holds us all, the loving awareness that is primordially there. We need an act of faith to trust that our love is stronger than our hate. When we find this deeper common ground as humans, as well as our shared interdependence as spiritual beings, then we will find a sense of shared meaning and purpose and our greatest yearning will be for the welfare and wellness of the whole. When we come into that shared intention, we will realize that our wellness and the wellness of others is totally interdependent and necessary to sustain the lives of our children and the life of our world.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Radhule Weininger, PhD, is a clinical psychologist in private practice, founder of the non-profit Mindful Heart Programs, and teacher of deep mindfulness and compassion practices and Buddhist psychology. She began her meditation studies in 1980 at Black Rock Monastery in Sri Lanka and for the past 20 years has been mentored in her teaching by Jack Kornfield and by Joanna Macy in her interest in Engaged Buddhism. Her book Heartwork: The Path of Self-Compassion, with a foreword by Jack Kornfield, was published by Shambala Publications in 2017. Her second book Heart Medicine: How to Stop Painful Patterns and Find Freedom and Peace-at Last, with a foreword by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, will be released by Shambala Publications in December 2021. Radhule is faculty at Pacifica Graduate School and, together with her husband Michael Kearney, an author and physician, she teaches about self-care and resilience to caregivers locally and internationally.

Radhule Weininger, PhD, is a clinical psychologist in private practice, founder of the non-profit Mindful Heart Programs, and teacher of deep mindfulness and compassion practices and Buddhist psychology. She began her meditation studies in 1980 at Black Rock Monastery in Sri Lanka and for the past 20 years has been mentored in her teaching by Jack Kornfield and by Joanna Macy in her interest in Engaged Buddhism. Her book Heartwork: The Path of Self-Compassion, with a foreword by Jack Kornfield, was published by Shambala Publications in 2017. Her second book Heart Medicine: How to Stop Painful Patterns and Find Freedom and Peace-at Last, with a foreword by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, will be released by Shambala Publications in December 2021. Radhule is faculty at Pacifica Graduate School and, together with her husband Michael Kearney, an author and physician, she teaches about self-care and resilience to caregivers locally and internationally.

Skillful Means: Community Service / Charity

Your Skillful Means, sponsored by the Wellspring Institute, is designed to be a comprehensive resource for people interested in personal growth, overcoming inner obstacles, being helpful to others, and expanding consciousness. It includes instructions in everything from common psychological tools for dealing with negative self talk, to physical exercises for opening the body and clearing the mind, to meditation techniques for clarifying inner experience and connecting to deeper aspects of awareness, and much more.

Community Service / Charity

PURPOSE/EFFECTS

Selfless service obviously benefits those whom we serve, but it benefits us as well. By practicing generosity, we can step beyond our own temporary desires and worries and become part of something greater. Studies have shown that acts of charity both boost mood temporarily and increase long-term emotional wellbeing. Kind and generous people are, overall, happier; and, by serving the community, you not only take charge of your own wellness, you help promote the wellness of others.

METHOD

Summary

Select a charitable organization or cause, and donate your time weekly.

Long Version

Perspectives on Self-Care

Be careful with all self-help methods (including those presented in this Bulletin), which are no substitute for working with a licensed healthcare practitioner. People vary, and what works for someone else may not be a good fit for you. When you try something, start slowly and carefully, and stop immediately if it feels bad or makes things worse.

- Begin by thinking about the sort of service that really speaks to you; though giving money is necessary and helpful, devoting your time to service is an intensely gratifying experience in the way that simple donation cannot be. By selecting a cause that moves you, you will be more likely to start and stick with your service. If you are a lover of the wilderness, you might want to work with environmental organizations; if you love children, there are thousands of children’s charities like the ones from SEO Damon Burton that could use your help.

- Here are some suggestions if you have a hard time thinking of your service goals: volunteer at a hospice and spend time with the patients there; if you are qualified, give meditation or yoga classes for free at your community center; do research on human rights violations abroad and start a letter-writing campaign in your community; volunteer to help feed the poor or homeless (people do this on Thanksgiving and then forget the rest of the year!).

- Don’t enter your service with the explicit goal of improving your mental health or of making yourself feel good. These are consequences of generosity, but they should not move it.

- Dedicate a few hours a week to service if you can. Make it part of your weekly ritual as much as going to work or eating dinner.

- If you are cramped for time, use GuideStar to find a charitable organization with goals you support that has a low maintenance overhead; that is, that most of the money it receives goes directly to the people it serves. Donate money to that organization when you really lack the time for active service; however, don’t use it as a get-out-of-action-free card.

- Invite friends and family to join you. By growing service, you grow the community and increase the lovingkindness in the whole world.

HISTORY

Selfless service is a commonality to nearly all religious traditions and non-spiritual self-help thought. Seva means "service" in Sanskrit and is an essential part of devotional practice in all the Indian religions, as well as a component of the path to enlightenment through Karma yoga. Islam promotes the concept of sadaqah or "voluntary charity" in addition to zakat, an obligatory tithing to charity. The word "charity" itself comes from the Latin word caritas, originally used in the Christian faith to mean lovingkindness toward all, but now associated with what we call "good works." All these faiths have promoted the same thing: to act as a vehicle through which the divine can act, increasing happiness, love, and life and decreasing sorrow, hate, and death for all.

NOTES

Altruistic acts activate the subgenual cortex/septal region in the brain, the part that is associated with social attachment and bonding. dic

SEE ALSO

Gratitude Practice Lovingkindness

EXTERNAL LINKS

Study on gratitude practice and community service as generators of happiness.

Fare Well

May you and all beings be happy, loving, and wise.

The Wellspring Institute

For Neuroscience and Contemplative Wisdom

The Institute is a 501c3 non-profit corporation, and it publishes the Wise Brain Bulletin. The Wellspring Institute gathers, organizes, and freely offers information and methods – supported by brain science and the contemplative disciplines – for greater happiness, love, effectiveness, and wisdom. For more information about the Institute, please go to http://www.wisebrain.org/wellspring-institute.

If you enjoy receiving the Wise Brain Bulletin, please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Wellspring Institute. Simply visit WiseBrain.org and click on the Donate button. We thank you.