News and Tools for

Happiness, Love, and Wisdom

volume 13.6 • 2019

In This Issue

The Science of Language, Self-Talk and Emotion

© 2019 Brian Pennie

“Never let the fear of striking out keep you from playing the game.”

–Babe Ruth

Language is powerful. It’s how we acquire many of our fears. I suffered from chronic anxiety most of my adult life; the physical sensations of which were focused around my chest. Fully supported by an overactive mind, I developed a morbid fear of my own heartbeat; a difficult thing to escape for sure.

In a bid to run away from these fears, I ventured into the world of addiction. Paralyzed by my own mind, this is where I stayed for 15 years. With the help of meditation, I have been free from anxiety and addiction since 2013. But even today, I get slightly agitated when I hear the word “heart.”

My own experiences might seem a little extreme, but have you ever woken up in the dead of the night, completely overwhelmed by your own mind.

Why is this so powerful?

Because how you think and the language that you use is a vehicle for emotion.

A theory of language, self-talk and emotion

“The limits of my language are the limits of my world.”

–Ludwig Wittgenstein

Negative self-talk, rumination, compulsive thinking, and unrealistic rule-following are found in most forms of human suffering. Is there anyone who cannot relate to this?

Relational Frame Theory (RFT) is a novel account of language, self-talk, and emotion that offer’s a powerful explanation of why we engage in these harmful behaviors.

At its core, RFT argues that language and self-talk are relational in nature, where ‘relating’ is a type of covert behavior that involves responding to one stimulus in terms of another. Take this sentence: “a seat is the same as a chair.” In this case, seat and chair are related as similar. This is the simplest form of relating, but stimuli can be related in a variety of different ways.

Greetings

The Wise Brain Bulletin offers skillful means from brain science and contemplative practice – to nurture your brain for the benefit of yourself and everyone you touch.

The Bulletin is offered freely, and you are welcome to share it with others. Past issues are posted at http://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin.

Rick Hanson, PhD, edits the Bulletin. Michelle Keane is its managing editor, and it’s designed and laid out by the design team at Content Strategy Online.

To subscribe, go to http://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin.

For example, “feeling sad is opposite to feeling happy”, or “mindfulness is a type of meditation.” The latter is a hierarchical relation, where mindfulness is contained within meditation. You can also have comparative (i.e. more-than) and spatial relations such as “whiskey is stronger than wine” and “the chair is beside the table.”

It gets more complex as relations are combined. For example, “yesterday was a lousy day for me, but today is better.” For RFT, the reference to “me” is a self-based relation co-ordinating the word “me” and “me the actual person.” This sentence also includes a temporal relation between yesterday and today and a comparison relation with today being better.

It’s important to note several things here. Some are standard in existing theories of language, while others are a little different.

First, for RFT, language and thinking are the same types of behavior. In fact, they are the same behavior. That means that rumination, compulsive thinking, unrealistic rule-following, and negative self-talk are the same type of behavior. That is, they are all relational.

Second, language is symbolic (i.e. relating words to real things). For example, the word “seat” is something we have chosen to represent an actual seat. Thus, the word and the object are relationally co-ordinated; that’s what you’re doing when you use the word “seat.”

Third, language is generative. This means we can learn new relations without being directly told, or even being aware of it. For instance, if you know whiskey is a strong liqueur, and I tell you that poitín is a type of whiskey (i.e. they are now coordinated), what you know about whiskey will transfer to poitín, even though you only just heard about poitín. This is a key facet of how we learn.

Fourth, the relational nature of language provides a vehicle for emotion. That is, emotions travel through words and thoughts. As a result, rumination, compulsive thinking, unrealistic rule-following, and negative self-talk — all forms of relating — are key vehicles for emotional and psychological pain.

The symbolic nature of language

Ludwig Wittgenstein was one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century. He produced two major pieces of work, both of which had an enormous impact on the sciences, and still does to this day.

His first piece of work addressed a central problem in both philosophy and science: how language and thought are related to reality. He proposed that for thoughts and language to make sense, they must be represented in reality in the form of pictures; an objective reality, if you will.

In the photograph below, there is a man sitting in a chair with a table between his legs. There is a book on his head and a ladder leaning against the wall. Each of these statements can be represented in reality, and therefore make sense. That is, when you hear the words, you can paint a picture in your mind. It is this relationship — between words and reality — that underpins the symbolic nature of language. RFT is consistent with this theory but sheds greater light on how objects, pictures and words are related.

RFT also aligns with Wittgenstein’s later work. He argued that human language was a type of social game, where the meaning of words can only be found in their use.

The arbitrary nature of language

Language, for the most part, is arbitrary and socially defined. What does this mean? For any word, when it was first given a specific meaning, someone at some point in history made it up. Did you never wonder why the word “window” refers to the thing you look out of, and not to a dog instead?

This is the same for all words. They might have evolved differently through other languages, but at some point in time, words were simply plucked out of thin air.

There’s another level whereby language is arbitrary. Think of how the word “table” resembles an actual table. You can’t, of course, because there is simply no resemblance between the word and the object. The relationship is completely arbitrary. That’s why we say that language is symbolic.

It’s this arbitrariness that’s believed to be the reason why animals can’t think in the same way that humans do. Animals and non-verbal humans can only learn to relate stimuli based on their physical properties; they cannot relate them as arbitrary.

The generative nature of language

When children are about two years old, psychologists and linguists often talk about a language burst. This occurs when new words and sentences, which were never directly learned, seemingly appear out of nowhere. This is clearly recognizable when children use bad grammar. For example, it’s common for children to use words like “mouses,” “I runned,” and “I gived” which they would not have learned from adults. Well, I hope not anyway.

While the generative nature of language is crucial for our development, our ability to generate relations so quickly also has a downside.

Imagine you meet the man/woman of your dreams. For argument sake, we’ll say it’s a man called Bill. Your whole body flutters with just the sound of his name. Along comes a friend and tells you that Bill was seen leaving your best friend’s house in the middle of the night. All of a sudden, your heart is in your throat, and your mind is filled with uncertainty, worry, and anger.

How does this happen?

It happens through the generativity of language. In simple terms, your friend created a relation between Bill and your best friend, and your mind added deception, lost love, and no future. But remember, you never even seen this apparent cheating, and neither did your friend, so you don’t even know if it’s true. This is the dark side of language, and how its generative nature can cause emotional pain.

Language as a vehicle for emotion

From the ‘cheating’ example above, you can see how language is a vehicle for many of our emotional experiences. Fully supported by scientific data, RFT provides a novel way of explaining how this process works. When stimuli are related, new stimuli acquire the corresponding psychological properties of the original stimuli in the relationship. For example, if you like oranges, and you’re told that clementines are like oranges, the psychological properties of ‘liking’ will transfer to the clementines.

Research also shows how this process operates at a biological level. If you salivate when you think of a lemon, and I tell you that a “something” is like a lemon, you will salivate to the “something” because it is now coordinated with a lemon. You couldn’t stop yourself if you tried. Just like relating, this transfer of psychological properties often occurs in complete unawareness.

To illustrate this more clearly, consider my own personal experiences when I was addicted to heroin. Through arbitrary relatedness, the spoken word “heroin” provided many of the same psychological properties as an actual bag of heroin. I often remember being in severe withdrawal, but by simply hearing I was about to get a fix, my functioning would dramatically improve.

The picture on the left is two years before I hit rock bottom. The picture on the right was taken in 2017, four years after I reclaimed my life.

The picture on the left is two years before I hit rock bottom. The picture on the right was taken in 2017, four years after I reclaimed my life.

On one occasion, I remember feeling fine until I realized I had forgotten to take my methadone. Within seconds, my stomach was upset, I began to shiver, and sweat was streaming down my cold body.

“I am, by calling, a dealer in words; and words are, of course, the most powerful drug used by mankind.”

―Rudyard Kiplin

Language and Fear

The relationship between language and fear is best illustrated by a process known as fear conditioning, a form of learning where actions become associated with fear-producing stimuli. For example, if a person goes to a shopping mall and has a panic attack, they’ll associate future shopping trips with fear and panic.

This form of learning has also been demonstrated with language. In one research study, individuals were repeatedly presented with a meaningless word (e.g. “VUK”) which was followed by an electric shock. This resulted in a learned association where they became fearful of the word “VUK”, even when it was presented on its own.

The word “VUK” was then repeatedly associated with another meaningless word “ZID”, without the shock. The word “ZID” was then presented on its own, and even though it was never directly paired with the shock, it still produced a fearful response.

Words alone provided a vehicle for fear.

Why is this important?

Because it’s not just fear. Language is the currency for many of our psychological experiences. If you think and talk happy, you’ll feel happy. If you think and talk confident, you’ll feel confident. But if you’re mind-set is based on fear, this is how you’ll act and feel.

Language and fear in the real world

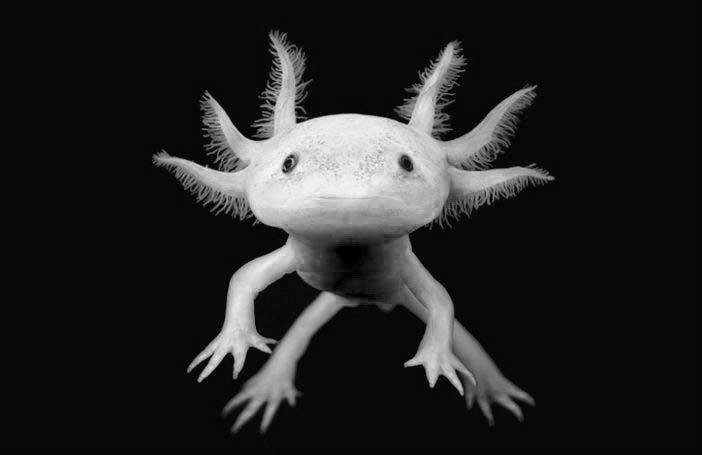

Imagine you have a fear of snakes and reptiles. You plan to go on holiday to Mexico, and someone tells you to be careful of Mexican axolotls.

You ask: “what is a Mexican axolotl?”

“A type of salamander”, they say.

You’re unsure what a salamander is, so you check the Oxford English Dictionary. This is what you’ll find: “a mythical lizard-like creature said to live in fire or to be able to withstand its effects.”

You already had a fear of lizards, so now you’re absolutely petrified of Mexican axolotls. You even think of cancelling your holiday.

The thing is, your fear is based purely on language; through what you’ve read, and what you think. You’ve never even seen a picture of a Mexican axolotl. Never mind come face to face with one.

This is what a Mexican axolotl looks like.

Not so scary is it?

Words hurt

“Sticks and stones may break my bones but names will never hurt me.”

Unfortunately, this is not true. Words are powerful. Words hurt.

Take anxiety and stress. These are not just mental concepts. They are physical reactions to both real and/or perceived difficulties. Both are linked to our fight and flight response, the body’s reaction to challenging events.

This process evolved as a basic survival mechanism and was highly adaptive thousands of years ago. But we are not fighting sabre-tooth tigers anymore.

We are fighting with our own minds.

We are worrying about deadlines, relationships, money, and popularity.

We are fighting about what we should have done, and what we’re afraid to do.

However, our brains are easily confused. It will spit out signals thinking a deadline is a physical fight. This is the essence of modern day stress and it is intrinsically linked to language. I can’t fight or run away from my own heartbeat, but tell that to my brain.

Change your self-talk, change your life

I was instantly taken by the science of self-talk and emotion, but one instance, in particular, blew me away. Yvonne was head of the psychology department in my first year at college. But she soon made a big life decision, found a good Three Movers NYC cost calculator, did some estimating, and moved to Ghent University and we lost contact for several months. When I eventually emailed her, she asked me if I wanted to chat via Skype. As much as I wanted to, I was terrified of Skype and gratefully declined.

I had never done a video call before, but there was another reason I was fearful, one I was completely unaware of. How we speak and think is grounded in our history. That is, we are reinforced by what works, or what appears to work, and this determines our future behavior. Staying out of sight had served me well in addiction, so this was driving my fear. Yvonne realized this and sent me an email with a hidden intervention.

Before Yvonne went to Ghent, we spent many hours in her office talking about language and emotion. These were some of the most inspiring conversations of my life, and Yvonne used this as the focus of her intervention. In what first seemed like an overly repetitive email, she linked the proposed Skype call with our previous meetings. The email went something like this:

Hi Brian, don’t be worrying about Skype. It’s easy. It’s just like our conversations in the office. We’ll have a great chat about language and emotion and it will be fun. Skype is so simple when you think of it. It’s exactly the same as our previous meetings. It will be just like we are sitting in my office. We’ll be still face-to-face. It’s so easy. It will be great fun, exactly like our previous chats.

After reading the email, I thought to myself: “That sounds so simple. What the hell was I afraid of? I can’t wait to Skype Yvonne.”

As I stood up to put away my laptop, it hit me: “Holy sh*t! What the hell just happened?” In the space of a few minutes, my fear of Skype had not just vanished, it was completely flipped on its head. “How was this possible? Was Yvonne some kind of wizard?”

When I sat down to read the email again, I recognized the intervention. It was genius. I conducted a retrospective analysis and found that Yvonne had relationally coordinated our office chats with the proposed Skype call. As a result, the psychological properties of easy, fun and relaxed, transferred over to Skype. My self-talk had shifted, and so did my willingness to act.

This can be a difficult intervention to implement on your own, and I had a wizard to help me, but below are four techniques that can help you change how you speak and think, and as a result, change how you feel and act.

1. Replace reactive language with proactive language

“I used to think that the brain was the most wonderful organ in my body. Then I realized who was telling me this.”

–Emo Philips

We all have a story, and this is written by the words we use. If you tell yourself you’re depressed, you’re going to act accordingly. If you tell yourself you suffer from anxiety, it’s likely that you will. It is therefore critical to choose your words carefully, especially when talking to yourself.

In a world full of distractions, our stories about procrastination have become particularly problematic, with many people crippled by an inability to act. I’m certainly not immune to this modern-day phenomenon, and as I sat in my kitchen writing this article, I found myself struggling with the very thing I was trying to write about.

The sections above took me over a week to piece together. Distracted on many fronts — some important, some not — my self-talk sounded something like this: “Maybe I should start this tomorrow,” “Maybe its best if I do X first,” “Am I hungry?,” “Oh, I’ll just check my social media first. Then I’ll get back into it.”

When this kind of internal monologue goes unchecked, nothing gets done. When you do catch it, however, it is vital that you replace it immediately. I simply switch all of the above with “just do it,” or if I’m feeling less motivated, “let’s just make a start.” Sometimes a start is all you need, and momentum takes care of the rest.

Less obvious language that can stop you taking action should also be avoided. For example, reactive words such as “I can’t,” “if only,” “I must,” or “he/she made me feel like that,” should be replaced with proactive words such as “I will,” “I choose to,” and “let’s look at this another way.” This practice is empowering, and when you make the switch, even your posture will change.

In challenging situations, you should also keep track of the questions you ask yourself. For instance, replacing “why me?” with “what can I do about this?” will instill a sense of strength, directing you towards corrective action, rather than worrying about your problems.

2. Challenge your self-talk

“The words you speak become the house you live in.”

–Hafiz

I used to struggle with public speaking. For days before a talk, I’d fill myself with all kinds of anxiety-inducing thoughts. “What if you faint on stage?” “What if you have a panic attack?” “What if you can’t stop sweating?”

What do you think happened on the day? Damn right, I was crippled with anxiety. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy, or as Henry Ford liked once said, “Whether you think you can or you think you can’t, you’re right.”

It’s very different for me today. When any irrational thoughts that enter my mind, I identify and dispute them immediately. When I do this, it quickly becomes clear how irrational they are. I never fainted in my entire life. I’ve only ever had one panic attack. And as for sweating on stage, who cares. Most people wouldn’t notice anyway, and you can always wear black.

That’s me talking about “tactics for life” in Eir, Ireland’s largest telecommunications company.

That’s me talking about “tactics for life” in Eir, Ireland’s largest telecommunications company.

Not all problematic thinking patterns are irrational, however. Before a talk, my internal chatter might say: “this is going to be nerve-racking,” which is not always far wrong. When this occurs, I use a form of cognitive reappraisal by replacing “nerve-wracking” with “exciting.” This tactic works well in many stressful situations, as it is often our interpretation of events (i.e. the language we use), rather than the event, that determines our emotions and behavior.

3. The power of metaphor

“Unless you are educated in metaphor, you are not safe to be let loose in the world.”

–Robert Frost

Metaphors, which refer to one thing by mentioning another, provide an excellent tool for explaining difficult concepts. For example, when explaining how atoms work, you might say that “an electron circles around a nucleus in the same way that a planet circles around the sun.” From an RFT perspective, we are relating (as similar) a well-known entity (i.e. solar system) to a lesser known entity (i.e. an atom) to better describe how the latter works.

Metaphors can also be used on a psychological level to explain abstract concepts such as anxiety, acceptance, and suffering. When used correctly, the psychological properties from one reference point transfers over to the other, thus providing people with a more concrete understanding of their problems.

Here are two examples:

When someone is struggling with anxiety, they often try to fight back, which only creates more anxiety. A great metaphor for this involves a tug of war with a big anxiety monster.

You have one end of the rope, and the monster has the other. In between you, there’s a bottomless pit. You pull as hard as you can, but the monster is stronger and pulls you closer to the pit. You’re stuck. What should you do? You should drop the rope. Yes, the monster’s still there, but you’re no longer in a struggle with him. It’s the same for anxiety. When you stop struggling with it, you rob it of its power over you.

Many people resist change. They want to change their lives, especially if they are struggling, but often persist in the very behavior that caused their problems in the first place. The “person in a hole” metaphor describes this best.

A person aimlessly wanders into a field full of holes. Disorientated by past experiences, they fall into a big one. The sides are steep and they can’t get out. But they were lucky. They had a toolbox with them. Without thinking, they use a shovel to dig themselves out. This obviously doesn’t work, so they start digging with greater intensity. But this just leaves them deeper in the hole. Feeling dejected, they give up. Suddenly, like a blessing from the skies, a person walks by with a ladder and throws it into the hole. Finally, some luck. But what do they do? They pick up the ladder and try to dig themselves out of the hole.

It’s often difficult to see the wood from the trees, especially when you’re deep in the forest. It might be an alcoholic who continues to drink. Or a person with social anxiety who refuses to leave their house. This metaphor can help such people to see the futility of their current behavior.

Here is a comprehensive list of metaphors used by therapists and a link to a practitioner’s guide used in acceptance and commitment therapy.

4. Mindful self-observation

“Dialogue is about creating awareness through self-observation; it starts from the inside out, not the outside in.”

―Oli Anderson

Instead of trying to change how you think, sometimes it’s best to practice the art of self-observation. This simply means mindfully observing how you think and feel. For example, if I asked you to observe your bodily sensations, you can take a step back and focus on a specific area, such as your breath, pulse, or chest. If I asked you what you were thinking, you can observe this too. You might be planning for the week ahead, or worrying about money, but it’s possible to take a step back and observe these thoughts. It’s the same for feelings. If I asked you how you feel, you could take a step back and observe how you feel.

The point is, you can take an observer’s perspective of your thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations. However, you must simply observe, without engaging. Like the blue sky watching clouds drift by, or the person on the river bank watching the leaves float by, you watch them come and go, without engaging. This is important. Be the blue sky. Be the observer.

When you practice this regularly, you will create a sense of detachment from difficult thoughts and emotions, and when they do arise, they will no longer consume you.

Conclusion

Language is the currency for our self-talk and a vehicle for our fears. If you tell yourself you’re afraid, it’s likely that you’ll feel that way. It’s the same for many of our psychological experiences.

But you don’t have to suffer. If you want to change your relationship with fear, you do have a choice.

You can challenge your self-talk, or replace it with more proactive language. You can also use metaphors to better understand your fears. Finally, you can mindfully observe difficult thoughts and feelings, and accept them without engaging.

By doing so, you will create a sense of detachment. Words will lose their potency, and difficult thoughts and feelings will no longer control you.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

On October 8, 2013, Brian Pennie experienced his first day clean after 15 years of chronic heroin addiction. Instead of perceiving his addiction as a failure, he embraced a second chance at life and went to university to study the intricacies of human behavior. Since then, Brian has become a keynote speaker, a PhD student, an executive coach, and a university lecturer in Trinity College and University College Dublin, where he teaches the neuroscience of mindfulness and addiction. He is also a published academic author and he has just finished his first book, a memoir called Bonus Time. Brian also writes regularly about the tools, habits, and tactics that transformed his life. You can find his work on Medium, Quora, and on his website.

On October 8, 2013, Brian Pennie experienced his first day clean after 15 years of chronic heroin addiction. Instead of perceiving his addiction as a failure, he embraced a second chance at life and went to university to study the intricacies of human behavior. Since then, Brian has become a keynote speaker, a PhD student, an executive coach, and a university lecturer in Trinity College and University College Dublin, where he teaches the neuroscience of mindfulness and addiction. He is also a published academic author and he has just finished his first book, a memoir called Bonus Time. Brian also writes regularly about the tools, habits, and tactics that transformed his life. You can find his work on Medium, Quora, and on his website.

Ode to Impermanence

© 2019, Henna Inam

A bird takes flight

The clouds move in a vast blue sky

The wind dances a tattered prayer flag

A wildflower loses a petal

The dew ready to fall off its perch

The singing bowl ending its beckoning

A cricket offering its song

A joy in the heart

A quivering for the sublime

A yearning to hold this moment

An ache, an envy, a fleeting regret

A lover’s touch

A sorrow

Welcome each. And let it go.

For it will not stay.

Life is here. Now. Calling you.

Come play.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Henna Inam is the CEO of Transformational Leadership Inc. where she works as a top executive and team coach with C-level executives in Fortune 500 companies. Her book Wired for Authenticity serves as a touchstone for leaders who seek both authenticity and agility in a 24/7 dynamic, fast-paced workplace. She is a Board member of Engro Corp. where she serves as the Chair of the Board People Committee. Henna is passionate about advancing women in the workplace and is the organizer of the TEDxCentennialParkWomen. Join the thousands who subscribe to her blog at www.transformleaders.tv.

Henna Inam is the CEO of Transformational Leadership Inc. where she works as a top executive and team coach with C-level executives in Fortune 500 companies. Her book Wired for Authenticity serves as a touchstone for leaders who seek both authenticity and agility in a 24/7 dynamic, fast-paced workplace. She is a Board member of Engro Corp. where she serves as the Chair of the Board People Committee. Henna is passionate about advancing women in the workplace and is the organizer of the TEDxCentennialParkWomen. Join the thousands who subscribe to her blog at www.transformleaders.tv.

Conversations with Teenagers: Family Culture and the Everyday “Stuff”

© 2019, Melanie Medland

Part of the purpose of adolescence is to develop our very own unique and individual identity; it’s a time for learning how to be comfortable in your own skin as you show up in the world. That means separating from our parents, seeing things differently from the way they have taught us and, at times, taking such a strong stand it leads to a disagreement or an argument. We all have memories of our teenage years. Those awkward chats with parents about things we’d much rather not discuss; and the times when we so wished we could discuss something more openly with our parent. Watching how they functioned as adults and wanting to know more of how they did it.

As a parent you may find the teenage years can be quite challenging. The small and adorable child has disappeared, replaced by a large, somewhat moody individual who now has to be reminded of expectations that used to be commonplace. Easy chat has somehow vanished and they no longer wish to hear your opinion, especially when it doesn’t agree with theirs. Luckily there are still glimpses of that wonderful child and occasional wistful comments, interesting questions and random hugs that remind you just how worthwhile parenting an adolescent can be.

Balancing a busy family life, work demands, self-care and still maintaining significant relationships and friendships is a daily juggle which frequently leaves us parents short of time and wondering how we’re going to fit it all in. The day to day juggle is hard work and it’s easy to focus on the next job of the day in a constant whirl of activity from morning to night. Little wonder that time for deep and meaningful conversations with our teenagers is just not at our fingertips. Much less the inclination, energy or closeness that getting into a deep conversation requires. It’s not like sitting down with a girl friend or a mate and instantly getting to the heart of the thing that is bothering us. We don’t have that same wavelength vibe going on for a number of reasons, all very valid too. A conversation like that just wouldn’t be appropriate or right on so many levels.

But a close, connected relationship with our teenager would be awesome. So, how do we get there?

Everyday stuff and the daily environment is so important

Without the close and proactive everyday activities, we’re really going to struggle with the deeper stuff. Of course, we have rules and routines to make day to day living easier and yes, they’re vital. And of equal importance is the way in which family members routinely interact with each other and rub along together. I say rub along because, truthfully, there are times when we plain don’t like each other right now and we all just have to figure out how to get along because we’re family.

The things that matter happen under our noses without us even realizing it. If the main focus of our everyday conversations is around rules, reminders and criticisms then we will struggle to have a close relationship with our teenager. Or if we are plain and simply not available because something outside of the family is our focus then we will find that our adolescent/parent relationship is compromised.

Christian Gallen from attitude.org.nz points out “Little conversations matter, they lay a foundation for big conversations.” Be reflective about the main themes and tones of your conversations. Do they support and encourage your teenager? Or are they full of phrases that start with “You should …. “or “You need to …” or “Will you …. NOW.” Or are there big empty silences that stretch on endlessly? There will be a need (and at times strictly) to reinforce house rules and give reminders of behavior, expectations and, occasionally, consequences. And this is still essentially important. Adolescents need boundaries. They also need consistent loving and a parent they can engage with on a level that challenges and grows their thoughts about life. Understatement of the year: it’s a big job!

A healthy family culture will include varying amounts of the following:

1. Day to day communication

All of these check-ins need to happen daily, with genuine love and connection:

“Good morning”

“Good night”

“How was your day?”

“Good morning”

Make an effort to show your teenager they are important with these consistent check-ins, delivered with lightness and love. That means looking them in the eye 95% of the time, as opposed to calling out over your shoulder as you do something else. Whenever it’s possible, accompany your verbal comment with a hug, a touch, a smile or a gesture of affection. Let them see your genuine love for them that is so easily buried under the busyness of life.

2. The language of touch

In passing pause and rub their shoulder or the top of their back, ruffle their hair or have a high 5. You will know what is comfortable for your teenager. Not everyone is ‘huggy’ so make sure you respect their personal preferences. And while light touch might be appropriate in your home, it may just embarrass them in public so be mindfully aware.

3. Family traditions

What makes your family unique? Dinnertime conversations, laughter, routines, family activities, expectations and boundaries. Some of these routines may have been going since childhood and are no longer appropriate, or they may be completely new. Just because you haven’t done them before doesn’t mean it’s not time for a new family tradition. If you feel like the daily flow isn’t working for your family, then change it. The blessing of tweens and teens is that this is a perfect opportunity for their input. Ask them what they like about their family and their home, what they don’t like and if there’s anything that they’d like to see changed. Open a discussion and see what comes out of it. I don’t mean simply agreeing to their ideas of ice cream for breakfast and keeping their phones in their rooms (some things are non-negotiable and that’s your call as the parent and bill payer). However, their input is brilliant, and they’d love to be involved.

4. Driving in the car

But obviously not while you’re giving them a driving lesson … Car time is a great opportunity to have a deep conversation. You’re in a confined space so you can hear each other easily but, as anyone who watches car karaoke will know, that sometimes uncomfortable eye contact pressure is off. If possible be side by side instead of front seat/back seat and devices need to be off. Establish the “What’s said in the car stays in the car” rule. You may use this time to check in in a more in-depth manner with questions like “What’s been on your mind?” as an opener. Or get them chatting about something more specific, like the science assignment that’s due and how it’s going. Be prepared to share your answers too as you get your teenager used to chatting back and forth. Keep it as relaxed as possible, after all you’re driving, but if it’s appropriate you can always stop for a hot chocolate or a walk.

5. Text, messenger and notes

These forms of communication will work for you if they’re already established forms of communication used for positive things. If you pop up in their feed on a regular basis telling them they’re special and you love them, and you hope they’re having a good day then you will find these non-verbal forms of communication are a great way of communicating with your teenager. The huge advantage is that you both have time to think about and craft replies. If a crisis has hit with your teenager, don’t expect these to be useful if they’re not already being used. You will need to start popping up regularly to build a trusting habit so expect to invest in 1 - 3 months of work at a lighter level first. If you were wondering, now is a great time to start. Don’t wait.

6. Make time

It’s funny how dinner prep and cooking time is often when a teenager pops up at your elbow for a random chat. If it’s possible to stop then please do. Put down the noodles, it’s really not about you. This is the best possible time to access a thought that’s on top for your child so even if it means dinner will be five minutes later than anticipated, take the time to stop what you are doing and chat. Or they may be able to help with dinner, an extra pair of hands is an excellent trade-off for chatting time. And dinner prep chats are another great time for chats with less eye contact. Some kids really do find this way less threatening and are far more likely to open up.

If you really don’t have the time to stop then give them a hug and make a time to chat with them after dinner. And keep that time. Building trust is so crucial and important. Unfortunately, the thought may have been worked through already and lost its urgency by that later time but by checking in properly, making the time to sit down and be available you will still be following up on your word and demonstrating that they are important.

Sometimes it just feels like you have to take a step backwards to go forwards. When the going gets rough some stuff may have to go in order to move forwards. That’s called effective parenting and its part of the juggle.

7. Have quality time

Make your interactions count. It’s not very effective to devote 30 minutes ‘hanging out’ with your teenager when you’ve got a million other things to do. If you want to ‘hang out’ then great. But be present while you’re doing it. Listen to them and share the love. Otherwise don’t bother. Less can be more. Support your child with strength and love. Be proactive, genuine and authentic.

The Wellspring Institute

For Neuroscience and Contemplative WisdomThe Institute is a 501c3 non-profit corporation, and it publishes the Wise Brain Bulletin. The Wellspring Institute gathers, organizes, and freely offers information and methods – supported by brain science and the contemplative disciplines – for greater happiness, love, effectiveness, and wisdom. For more information about the Institute, please go to http://www.wisebrain.org/wellspring-institute.

If you enjoy receiving the Wise Brain Bulletin, please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Wellspring Institute. Simply visit WiseBrain.org and click on the Donate button. We thank you.

Children tend to listen more or less as much as they feel listened to

It’s worth pointing out that children will only listen as well as they feel listened to. If you feel that your kids don’t listen to you then may I gently suggest that perhaps you are also a part of the problem here … And the same applies when they sometimes don’t listen, maybe they only feel sometimes listened to. Wherever you are on your parenting journey right now know you are exactly where you need to be. There will always be things to learn so please don’t beat yourself up if you ever feel inadequate to the job. Parenting is an enormous task and we are never, ever going to always get it right.

Teenagers need to know they are heard and respected. Lip service won’t cut it. They need quality parenting that reflects your values and beliefs and empowers them to become better people. They deserve to have their complaints heard and reflected back to them. And they need to receive empathy and support from you. A tricky balance when you are also the boundary setter and enforcer, on the up-side, boundaries are easier to enforce when you’ve got an open dialogue going with your teens.

Active Listening

So much of the stuff we say is about us. And it’s not helpful to have an interaction with your teenager when you’re bringing all your ‘stuff’ to the discussion. Begin the habit of letting your teenager work out their problems themselves, with you available as their supporter. We have two ears and one mouth for a very good reason.

Be friendly, interested and curious. Show your child you care about them by taking time to be interested in the things that interest them, make time to develop connections with them.

Your body language shows involvement and attention. Take a second to stop, pause, and mirror them. Give them the time and attention they need. It is their time to talk, so let them talk. Silence is an excellent prompt. Your job is to listen to what they are telling you. Really listen. You are not expected to reply at all necessarily, and definitely not immediately. This is the time to listen to hear and understand, instead of listening to answer.

You will be doing this properly if you can reflect back what you’re hearing them say. For example, you might say, “So this happened … and then you felt ……. and now …….” They will correct you if you get it wrong, which is great because as they explain it to you, they are also explaining it to themselves. The phrase “I heard you say …” is really useful. Often, when something has happened all it needs is to be reflected on. You really don’t need to fix anything or solve anything. That is your teenager’s job. Your job is to let them talk out all the swirls in their heads. With no blockers (see below) allowed. Genevieve Simperingham from peacefulparent.com nails it when she says ”To actively listen means to listen with genuine interest, with patience and presence, to listen with our ears and our heart.”

The biggest difference you can make for them right now is to treat them like an adult, not like a naughty child.Trust that they know the answers within themselves and be there to help them, support them and let them find them.

Roadblocks

Stop fixing - this is a huge one for me. So often I want to jump in with a solution to a problem that seems enormous to them and pretty insignificant to me. But am I teaching them to figure it out for themselves by doing this? Not even a little bit. Instead I’m shutting down a chance to hear them, to guide them and to let them learn to solve problems. As a busy parent this is huge because my time is so precious. And the problem can seem so trivial. But back off with the fixit solutions. They’re what you might have done or what you think they should do. That word should. Takes away all the choice in the situation. Instead guide them to choose. Making choices is the best way of learning how to deal with a situation. Get them to brainstorm their ideas, throw in a couple of your own as suggestions if you must, but accept all thoughts. When the discussion comes up about where to go next you get to talk through solutions before they choose the one they think will work best for them.

Other roadblocks that just slow down the communication process:

Criticizing: is a harsh way to shut down a conversation. This also applies to criticizing others; if your teenager listens to you criticizing other people, how can they be sure you’re not going to criticize them as well? If you want them to trust you, choose to behave with integrity.

Diagnosing: cuts off a lot of possibilities. No one has all the answers.

Advising: stops the curiosity of problem solving and being open to their input.

Moralizing: you’re justifying, and judging based on your own values. The point is your teenager is trying very hard to develop their own values.

Threatening: my way or the highway just won’t cut it anymore.

Reassuring: how can you possibly know everything will be ok, especially if you’re not personally following up with some form of action?

Encouraging: is only useful when your teenager has ownership of the problem-solving process.

Closing thoughts

Small daily interactions count more than you realize. If you want to be the parent of a teenager who has a close and responsive relationship, then don’t wait for a crisis to hit. Be proactive and get your parent/teen relationship right when things are going well. You may even have to proactively instigate some feel good, going right times. Your teenagers are still your children and they still look to you for guidance, reassurance and love. Don’t be afraid to have a fresh start with them if you need to, but most of all don’t forget to keep loving them.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Our teenagers are facing pressures we never had to deal with as they move from child to adult. Unfortunately suicide is becoming a response they turn to as their path becomes murky and difficult. Melanie Medland successfully supported her daughter through severe teenage anxiety and depression, including suicide attempts. She is now using her knowledge to coach and support parents of teenagers with anxiety and depression. Visit www.movingthrough.net for more information.

Our teenagers are facing pressures we never had to deal with as they move from child to adult. Unfortunately suicide is becoming a response they turn to as their path becomes murky and difficult. Melanie Medland successfully supported her daughter through severe teenage anxiety and depression, including suicide attempts. She is now using her knowledge to coach and support parents of teenagers with anxiety and depression. Visit www.movingthrough.net for more information.

Skillful Means: Community Service / Charity

Your Skillful Means, sponsored by the Wellspring Institute, is designed to be a comprehensive resource for people interested in personal growth, overcoming inner obstacles, being helpful to others, and expanding consciousness. It includes instructions in everything from common psychological tools for dealing with negative self talk, to physical exercises for opening the body and clearing the mind, to meditation techniques for clarifying inner experience and connecting to deeper aspects of awareness, and much more.

Community Service / Charity

PURPOSE/EFFECTS

Selfless service obviously benefits those whom we serve, but it benefits us as well. By practicing generosity, we can step beyond our own temporary desires and worries and become part of something greater. Studies have shown that acts of charity both boost mood temporarily and increase long-term emotional wellbeing. Kind and generous people are, overall, happier; and, by serving the community, you not only take charge of your own wellness, you help promote the wellness of others.

METHOD

Summary

Select a charitable organization or cause, and donate your time weekly.

Long Version

- Begin by thinking about the sort of service that really speaks to you; though giving money is necessary and helpful, devoting your time to service is an intensely gratifying experience in the way that simple donation cannot be. By selecting a cause that moves you, you will be more likely to start and stick with your service. If you are a lover of the wilderness, you might want to work with environmental organizations; if you love children, there are thousands of children’s charities that could use your help.

- Here are some suggestions if you have a hard time thinking of your service goals: volunteer at a hospice and spend time with the patients there; if you are qualified, give meditation or yoga classes for free at your community center; do research on human rights violations abroad and start a letter-writing campaign in your community; volunteer to help feed the poor or homeless (people do this on Thanksgiving and then forget the rest of the year!).

- Don’t enter your service with the explicit goal of improving your mental health or of making yourself feel good. These are consequences of generosity, but they should not move it.

- Dedicate a few hours a week to service if you can. Make it part of your weekly ritual as much as going to work or eating dinner.

- If you are cramped for time, use GuideStar to find a charitable organization with goals you support that has a low maintenance overhead; that is, that most of the money it receives goes directly to the people it serves. Donate money to that organization when you really lack the time for active service; however, don’t use it as a get-out-of-action-free card.

- Invite friends and family to join you. By growing service, you grow the community and increase the lovingkindness in the whole world.

Perspectives on Self-Care

Be careful with all self-help methods (including those presented in this Bulletin), which are no substitute for working with a licensed healthcare practitioner. People vary, and what works for someone else may not be a good fit for you. When you try something, start slowly and carefully, and stop immediately if it feels bad or makes things worse.

HISTORY

Selfless service is a commonality to nearly all religious traditions and non-spiritual self-help thought. Seva means "service" in Sanskrit and is an essential part of devotional practice in all the Indian religions, as well as a component of the path to enlightenment through Karma yoga. Islam promotes the concept of sadaqah or "voluntary charity" in addition to zakat, an obligatory tithing to charity. The word "charity" itself comes from the Latin word caritas, originally used in the Christian faith to mean lovingkindness toward all, but now associated with what we call "good works." All these faiths have promoted the same thing: to act as a vehicle through which the divine can act, increasing happiness, love, and life and decreasing sorrow, hate, and death for all.

NOTES

Altruistic acts activate the subgenual cortex/septal region in the brain, the part that is associated with social attachment and bonding. We are hard-wired to find charity pleasurable in addition to our more selfish needs, not in spite of them.

SEE ALSO

Gratitude Practice

Lovingkindness

EXTERNAL LINKS

Study on gratitude practice and community service as generators of happiness.

Fare Well

May you and all beings be happy, loving, and wise.