News and Tools for

Happiness, Love, and Wisdom

volume 14.3 • June 2020

In This Issue

Heartfelt Inquiry into Core Beliefs

© 2019 John Prendergast, Phd

Excerpted from THE DEEP HEART: Our Portal to Presence. Sounds True, December 2019. Reprinted with permission.

In the closing circle of a recent retreat, a delightful woman in her early sixties shared what had touched her the most. She admitted that she had attended the retreat mostly to be closer to her daughter (who was also a participant), but what struck her most was that she had never realized how much her entire life had been ruled by a core limiting belief. She confessed that she never knew that such a thing even existed. Seeing her belief and beginning to feel some space from it was a liberating revelation for her, and she was delighted to come out of a box that she didn’t know she had put herself in for most of her life.

It’s like that for most of us. Core limiting beliefs form in childhood and mostly reside outside or on the edge of conscious awareness. They are core in the sense that everything about us organizes around them — how we relate to others, work, and take care of ourselves. They are limiting because they constrain us, holding us back from living our lives as wakefully, freely, wisely, powerfully, joyfully, lovingly, and creatively as we can.

Greetings

The Wise Brain Bulletin offers skillful means from brain science and contemplative practice – to nurture your brain for the benefit of yourself and everyone you touch.

The Bulletin is offered freely, and you are welcome to share it with others. Past issues are posted at http://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin.

Rick Hanson, PhD, edits the Bulletin. Michelle Keane is its managing editor, and it’s designed and laid out by the design team at Content Strategy Online.

To subscribe, go to http://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin.

Beliefs are mental maps — approximations of reality. They help orient us, and most are benign. Generally, the closer they correspond to facts, the more useful they are. Of course, some nonfact-based beliefs provide solace and meaning in the face of existentialn uncertainty — for example, the desire for a pleasant afterlife somewhere up in the fluffy clouds or in a celestial desert oasis.

Core limiting beliefs are particularly powerful lenses through which we see ourselves and the world. Our view of the world always has a corresponding view of our self. If we see the world as a hostile and dangerous place, we will also believe that we need to either armor or conceal ourselves in order to survive — becoming aggressive or invisible depending on our temperament and conditioning. Conversely, if we perceive the world as friendly, we will feel safe to let down our guard, come out of hiding, and shine just as we are.

Core limiting beliefs about our self can be stated in short, simple, and childlike sentences. A few examples include I am not good enough, I am worthless, something is wrong with me, I don’t deserve to exist, I am a mistake, I’m bad, I’m flawed, I am broken and beyond repair, I’m unlovable, and I don’t belong. There are endless variations on these basic themes, and it’s important that we recognize the specific form that they take in our own lives. For example, I’m flawed may take the form of I’m really screwed up (or something more vulgar) particularly suited to our family and culture. You can tell that you have correctly identified one of these beliefs when it evokes a strong emotional charge and contraction in your body

This happens because our core beliefs are a complex of semi- or subconscious thoughts with accompanying feelings and sensations. When I work with groups, I sometimes invite participants to try the following brief, unpleasant experiment

Take a moment to reflect on a compelling core limiting belief that you have about yourself. Keep it as short and simple as possible, using the language of a child. You won’t need to disclose it to anyone. Experiment with different variations until you find the form with the most charge. Once you have found it, notice the impact emotionally and somatically. Observe it carefully for a little while and note that it is caused by your thinking. Take a deep breath and let it go.

I then ask group members who are willing to share the impact of their core limiting beliefs without necessarily disclosing the belief itself. I frame the invitation this way because there is often tremendous shame associated with these beliefs. Invariably people report unpleasant feelings such as shame and fear along with sensations of gripping or freezing in the interior of their body — somatic contractions. Core limiting beliefs induce a shutting down and pulling in — an inner collapsing, gripping, and armoring. The stronger the belief, the greater the impact.

It may help to do this experiment by writing down a list of your top five “hits” and then narrowing your list down to one or two that seem most central. Try it now. Pick the belief with the most impact. It may seem strange or unpleasant, but keep in mind that these highly confining beliefs with their attendant emotional and somatic reactions are also entry points for discovering your fundamental nature, and they can work like keys to unlock the depths of your heart.

Some people find that speaking these beliefs out loud with a trusted friend or therapist helps them to identify which ones have the most charge. During the process of heartfelt meditative inquiry, which I will describe shortly, these beliefs may also further clarify or even dissolve to be replaced by ones that are closer to the core. When this happens, we simply continue with the inquiry. We discover and see through each layer with increasing clarity.

When people start to attune with their heart, they report a sense of homecoming.

Another way to recognize a core belief is to focus attention on a familiar emotional reaction — shame or fear, for example — or a somatic contraction, such as a knot in the solar plexus or the heart area. Take a few minutes to simply feel the feeling and sense the sensation as it is without trying to change it. Then ask yourself: “Is there a belief that goes with this?” Be quiet and wait, trying not to grasp with your mind for an answer. Usually the belief will bubble up quickly. Whichever approach you take to recognizing your core limiting beliefs — asking yourself directly, making a list, or starting with reactive feelings and sensations — you are learning how to look under the hood of your conditioning to discover the patterns that drive you. It’s a crucial step in freeing yourself from illusion.

How Do I Question a Core Belief?

Once you have recognized a core limiting belief, attune with your heart wisdom to question it. First, drop your attention from the head to the heart area.

It may help to put your hand over the center of your chest and imagine that you can inhale and exhale directly from this area. Take a minute to quietly attune. You are signaling a willingness to listen in a different way and are also entering into silent contact with your true nature as loving awareness. Poetically speaking, you are summoning your highest muse — heart wisdom, a blend of nonjudgmental clarity and lovingkindness that is always available.

You can sense when your attention shifts from your head to the heart. It’s as if your center of gravity drops down like a descending elevator into your midchest. Not only are you feeling into the heart, you are starting to take up residence there. You may sense a feeling of warmth, openness, and intimacy. When people start to attune with their heart, they report a sense of homecoming and often feel closer to themselves. When I sit with people who are finding their way home, I can feel a radiant glow in my heart area, which happens because we all share the same home as loving awareness.

It can take a minute or two for this shift to happen. Take your time. With practice, it can occur in seconds. Once it feels like your attention is grounded in the heart area, you are ready for the next step:

Ask yourself: “What is my deepest knowing about this belief?” Don’t go to your mind for an answer.

If your belief is that you are not good enough, for example, state your question like this: “What is my deepest knowing about this belief that I am not good enough?” Use the exact language that you have used to formulate the belief. The clearer your question is, the more precise the response will be

I know that I am being repetitious, but there is a reason that I keep reminding you to not go to your mind for an answer. Going to ordinary thinking is the single most common way to sabotage your inquiry. When you are willing to not know with your problem-solving, strategic mind, a different and more essential form of knowing becomes possible.

There is no right answer in this inquiry. In fact, there is no “answer” as such. Instead, we are inviting a holistic response. One of my reservations about Byron Katie’s “Work” (which I greatly appreciate in general) is that the first two questions in her protocol — “Is it true” and “Can you absolutely know that it is true?” — are binary. You can only answer yes or no, and you know beforehand that the correct answer is always no. Framing the inquiry this way tends to keep attention localized in the mind

Once we have clearly formulated a core belief, shifted our attention from the head to the heart, and then inquired into our heartfelt knowing, we let the question go, wait, feel, and listen. A response can come in any form. For example, when I inquire in this way, a response often comes first as a subtle sensation in the interior of my body. It’s as if something lights up inside. As I sit with this subtle sensation, letting it be with openness and curiosity, a word or image will usually arise to accompany it. It’s as if a pearl begins to materialize on the ocean floor, readying itself to be brought up to the surface by a deep-sea diver. I will check to see and feel if the arising word or image resonates with the original sensation, and it takes clearer shape as I do so. Sharing it with another person also brings it out from the private into the public domain, which makes the response even more potent.

This process of discovery varies from person to person. For some, a word or an image will immediately appear with or without any sensation. Others will experience a silent knowing of the complete irrelevance of their belief. The point is to discover how a response comes to you and then honor it. We honor our responses by consciously letting them in as gifts from the gods and then acting upon them. This deep dive into our inner knowing and re-immersion with a new, liberating understanding directly parallels what mythologist Joseph Campbell described as the hero’s (or heroine’s) journey

Protocol for Heartfelt Inquiry into Core Beliefs

- Identify a core limiting belief. Keep it short and note its emotional and somatic charge. Then let it go.

- Shift your attention from the head to the heart area.

- Ask yourself: “What is my deepest knowing about this belief?”

- Don’t go to your mind for an answer. Be quiet. Listen, feel, and sense. A response can come in any form.

- Let it in

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

John J. Prendergast, PhD, is a spiritual teacher, author, psychotherapist, and retired adjunct professor of psychology who now offers residential and online retreats.

For more, please visit http://listeningfromsilence.com/

Living on the Razor’s Edge

© 2020 Beth Kurland, PhD

I never was an ocean child —

travelling each summer to the mountains

on vacations

became home

at a young age

that familiar mass of solid rock

immovable, unshakeable

stable and strong

steady and mostly unchanging

the way I longed for life to be

the way I longed for life to be

when loss came too soon

holding the grief of my 15 year- old heart,

showing me

the fragility and preciousness of life

are inescapably one.

But the ocean

is wild

is moving, ever-changing

with its waves dancing, cresting

falling, receding

rising and crashing

in a cacophony of sound

and fury

unashamed.

And strange, that in this uncertainty

in this troubled and challenging time

I long for the ocean.

I long for my fear and sadness

to be held in these waters,

tears finding their home in the salt of this earthly

treasure.

Take me to the shore of this vast expanse

where I can watch the intensity of the waves —

the fear, the grief, the sorrow

the fierce love, the kindness

of all kindred spirits

Where from this vantage point

no wave is alone

no wave disappears

nothing solid,

but Interconnected.

Part of the whole

where all of humanity is held.

Working with Stress in the Workplace and Beyond: Three Practical Tools for Becoming Stress SMART

© 2019 Beth Kurland, PhD

A note to readers: This article was written before the global pandemic, but its message is as much relevant now as ever. While the article focuses on “workplace” stress, these tools and this three-step approach can be quite useful to address any day-to-day stress that people may be experiencing. As a clinical psychologist in practice, I am seeing many people experience heightened stress during this pandemic as they struggle with the challenges of working from home (many with the additional challenge of home schooling their children at the same time). I am seeing others struggle with immense challenges of how to open up and/or operate their businesses safely, and the stress that accompanies this. Many people are working longer hours, while others are facing significant stress and anxiety due to being out of work. Those whose work is full time parenting face their own challenges at this time as kids are out of physical school and trying to adapt to sudden and dramatic changes to their lives and routines. No matter what your life circumstance, I hope this article may offer you a helpful way to work with stress and bring greater ease into your day.

***

We all have habitual ways of dealing with stress that may range from ignoring our stress signals and plowing through our day, to walking around in a chronic state of unease, to flying off the handle or reacting in less than helpful ways when in the grips of stress. Even if we are fortunate enough to be well resourced, it can be easy to slip into old, unhelpful habits when it comes to stress. If you need cannabis products to help relieve your stress at the end of the day, you may visit the shop of Everyday Delta. Shop wide selection of brands from Geek Bar to Vaper Gate. Check out vapes online today.

Whatever one does for work, the workplace can be a source of especially high stress for many people. According to one Stanford study in 2015, workplace stress contributes to about 120,000 deaths each year and about $190 billion dollars in healthcare costs. The World Health Organization recently declared burnout (from workplace stress) an official medical diagnosis. While clearly this epidemic of work stress is complex and requires interventions on many levels, including making critical changes in the workplace environment, I would like to highlight how learning some simple mind-body strategies may be one helpful way for individuals (or employers who care for them) to take their well-being into their own hands.

In one recent and promising study, employees who reported struggling with work stress were offered an online, instructor-led mindfulness-training course for four weeks where they were taught various kinds of mindfulness meditation practices. Before and after the course, measures were taken of work-related ruminations, fatigue and sleep quality of the participants, and these measures were compared with a waiting list control group. Participants in the intervention group reported lower levels of rumination, decreased fatigue and improved sleep after the four weeks, and these differences continued to be present in three month and six month follow-ups. The researchers identified that the essential ingredient that helped participants achieve these positive benefits was learning to act with awareness and focus on moment-to-moment experiences (which they referred to as “the opposite of automatic pilot”). So learning to observe one’s thoughts and feelings without engaging with them, and coming back to the present — in effect, being able to interrupt ruminative thinking — is what the researchers believe explained the positive improvements people experienced.

While not everyone may be able to (or inclined to) participate in a formal mindfulness training such as the one in this study, how might one start to teach themselves or their employees to develop greater mindful awareness, step out of “automatic pilot”, and interrupt ruminations that contribute to stress and fatigue? I want to suggest a short, several step practice that combines developing mindful awareness with strengthening inner resources as a way to interrupt ruminations at work and develop more adaptive coping with stress. This practice is one I have used with my patients, and it is inspired in part by Rick Hanson’s work on growing inner resources. Importantly, it does not take much time in one’s day to implement and thus might be appealing to employees and employers alike

As a clinician working with many patients who experience chronic work stress, I have observed that there are three common ingredients that many people share:

- a difficulty noticing stress signals as they arise (thus operating on “automatic pilot”);

- a difficulty knowing how to step out of habitual reactivity and interrupt old, conditioned patterns of behavior (they lack a new way to respond to stress, though they would like to respond differently); and

- a vague intention to change their behavior without a clear plan for how to implement this.

So what is most needed in this case is: a greater ability to notice stress signals as they arise, a way of pausing to interrupt the stress response and access a new response to stress, and a way to practice this new response so that it can be used more readily. Finding balance is key, and for a thrilling break, explore judi bola resmi.

The practice below helps to grow these skills. The goal is not to teach people how to be stress free, which of course would be futile given our human condition and the world we live in, but rather to learn how to be “Stress SMART”:

S – See the stress signals that are arising

M – make time for a mindful pause

A – Anchor oneself with a resource to meet the challenges at hand

R – Rehearse, rehearse, rehearse

T - Track one’s small, daily successes and small steps forward

To make this more concrete, I offer three tools, as described below. The tool of the flashlight targets the first challenge by helping people to notice stress signals as they arise. The tool of the anchor helps to counter our habitual, conditioned responses and remain grounded and stable during the storms. The tool of the magnifying glass helps us to pay attention to our successes where otherwise we might overlook them, and to track our progress.

Tool One: The Flashlight

Goal: Grow the awareness to notice stress arising and pay attention in a new way.

Rationale: We need a flashlight because we can’t change what we don’t see. If we want to change how we respond to stress, we need to be able to see what is here. If you imagine walking in a pitch black room trying to get from point A to point B with furniture and other obstacles present, you would likely be tripping and stumbling at every turn. But if someone hands you a flashlight you are able to see more clearly. The obstacles are still there, but you can navigate with greater ease. The flashlight is a metaphor for mindful awareness and it allows us to observe physical sensations, thoughts, feelings and behaviors through a non-judgmental lens.

Being able to recognize stress signals as they are arising can be immensely helpful. When we are in “automatic pilot” and caught in the reactivity of limbic system activity, we can miss these signals. Yet our stress response is often like a kind of “false alarm,” similar to a smoke detector going off when the toast is burning and there is no real fire. Our bodies are wired to look for threats, and when we perceive a threat, this activates our “fight or flight” response, with its complex cascade of physiological and hormonal changes, preparing us to face a predator or run away (or in some cases freeze). While adaptive for our ancestors, in most cases neither fighting nor fleeing (nor the body revving up to do so) tends to help solve most of our modern workday challenges. Certainly some short term stress can be positive and can energize and mobilize us, but if left unchecked, chronic stress can be detrimental in the workplace. Learning to pay attention to our stress signals in new ways can help us become less reactive.

The Practice: Learning how to use the flashlight

Part One: Find a comfortable place to sit for a few minutes where you feel safe and relaxed. Take a moment to feel your feet on the ground and your body making contact with the surface that you are resting upon. Picture a TV screen in front of you and imagine that you could find a channel that shows scenes from your typical workday or week. Find a typical stressor or challenge that you experience at work and picture this as a scene on the TV screen as vividly as you can. You might imagine metaphorically shining a flashlight on the situation, bringing clear sight to what is unfolding. As you watch this scene unfold, begin to notice what the signs of stress are in your body when you are in that situation. Do you notice muscles tightening, constricted breathing, tension in your stomach, or something else? What are your body’s physical stress signals? Continue to watch that experience on the screen until you have a sense of how stress shows up in your body, as best as is possible. When you are ready, begin to notice what typical thoughts accompany this experience of stress. What do you say to yourself in this situation? (One example might be “oh boy, I have so much to do I’ll never get it all done!”). The thoughts may or may not be immediately obvious, so stay with this for a minute or more to watch the scene play out and get a sense of accompanying thoughts. Staying with this experience a bit further, begin to name some of the emotions you are experiencing. Is there frustration, irritation, anger, worry, disappointment or something else? Finally, picture your typical reaction. How do you behave when stress of this nature arises? Do you ignore your stress and stuff if away, do you say or do things that are unhelpful, do you get overwhelmed or paralyzed, or do you take skillful actions? As you do this exercise, try to practice being non-judgmental of whatever you are noticing. Try as best you can to bring a gentle curiosity and kindness to whatever you discover. When you are ready, let that scene fade and bring your awareness back to your body seated in the room. Write down what you noticed about how stress shows up in your body, in your thoughts, in your emotions, and in your behaviors.

You now have four important pieces of information about your stress response, and you can begin to bring greater awareness to these stress signals as you go through your day. You can intentionally start to notice moment-to-moment what is happening in your body, in your mind, with your emotions, and in your behaviors as your work day unfolds, and pay particular attention to those signals you identified that indicate stress rising.

Part Two: The Mindful Pause

Goal: Bring the tool of the flashlight into the workday on a regular basis.

Rationale: When we learn to take a mindful pause and can observe thoughts, feelings and physical sensations more mindfully, there is an opportunity to step out of automatic pilot, out of conditioned reactivity, interrupt the stress response, and choose how we might best respond. For example, when we notice tight muscles or shallow, tense breathing, there is an immediate invitation to soften and deepen the breath. When we notice irrational thoughts or ruminative worries about the future or past, there is an invitation to come back into this moment and to recognize how our thinking may be contributing to our stress. When we notice difficult emotions arising, there is an invitation for self-compassion and self-care.

To make this more concrete and to practice bringing the flashlight into your workday on a regular basis, pick certain times in your day when you will stop, take a mindful pause and make note of these four aspects of your experience. Build it into your day by pairing it with certain routines such as your lunch break, a natural break between tasks, right before you walk into your office, on a bathroom break or before you go into a work meeting. Practicing for short moments throughout the day on a regular basis will help to access the flashlight more easily as stress arises

These mindful pauses could be as short as 1-3 minutes in length. They might involve closing your eyes, setting a mindful timer, and/or following a short guided meditation to take a mindful pause, or you might do this as an eyes open exercise, bringing your full attention to the questions below. Ask yourself these four questions during the pauses:

- What sensations am I feeling in my body?

- What emotions am I experiencing? (acknowledge and name them and perhaps picture them sitting beside you as you make space for them).

- What thoughts are going through my head? Just notice with a kind, gentle attention, practicing a stance of openness and non-judgment. Pay particular attention to how your thoughts may be contributing to your experience of stress, especially if those thoughts are distorted, inaccurate, catastrophic, or focused on past or imagined future events (for example, “This is going to be a really stressful, crazy day,” “what I disaster”, “I’m such an idiot that I did that”, “I’ll never get through this work meeting”).

- End by asking – what is needed in this moment?

Tool Two: The Anchor

Goal: Grow the ability to anchor oneself with an inner resource that will help to respond to stress in a new way.

Rationale: In order to develop a new response to stress, we need to have an experience of this new response as a felt sense that we can come back to.

We need to practice something different in order to experience something different. Inspired by Rick Hanson’s work on growing inner resources, what inner resources might we develop and practice that could be most helpful when we come up against workplace stress? In particular, noting the four dimensions of our stress response (body sensations, thoughts, emotions and behaviors), we have the opportunity to develop resources that might target any one (or all) of these areas. For example, if physical tension is a significant reaction to stress that one notices, one might focus on developing an inner resource for relaxing the body. If ruminating thoughts are a major area of stress, one might develop a resource that helps to ground them in the present moment. If self-critical judgments are a source of stress, one might work on developing self-compassion. And if a person tends to fly off the handle under stress, they might work on developing the capacity to see a bigger picture and wider perspective to address this behavioral response.

The Practice: Think about the typical stressors you face in your workday (see the flashlight practices above) and think about what inner resource might help you handle this challenge. In particular, what is it in these moments of stress that you most need from yourself? Think about what you might want to experience in your body, in your mind, or emotionally, that would help act like an anchor and help you weather this storm. Or as Dr. Hanson asks, what, if it were more present inside your mind, might be helpful to meet this challenge? While you may not be able to change the external circumstances, what might be a wise or skillful response when this stressor arises? For example, if you experience stress every time you have to talk at work meetings, you might want to develop a growing sense of confidence in your ability to make contributions. If your stress tends to involve a constant sense of too much to do and not enough time, you might want to experience a greater sense of calm presence and ability to focus on what is right in front of you. If your stress involves interpersonal conflict, you might want to develop a healthy balance of assertiveness and empathy. Or use the examples from the paragraph above as well to guide you to identify an inner resource you want to cultivate

Once you have the resource that you want to grow, think about a time in your life when you experienced the resource that you want to cultivate. For example, you might recall feeling comfortable and confident speaking up and sharing at a group that you volunteer in if you are trying to develop confidence in sharing your ideas at work; you might recall a time during a very challenging moment where you kept your cool and remained calm and focused (if you are trying to develop calm presence). Whatever situation you pick, call it up in your mind and see if you might feel what it feels like in your body to experience that resource. If you are having difficulty coming up with a time when you felt this way, you might picture someone you know who embodies this quality. What does calm presence and a focused mind feel like? Where do you notice that in your body? Stay with the experience for several minutes and as Rick Hanson instructs, let it sink in; absorb and magnify this experience in any way you can. Finally, see if there is an image, a symbol, a word, or physical sensation that best represents this inner resource and make note of this as a way to quickly access your anchor in the future.

Throughout the day, and in the days to come, continue to practice coming back to your anchor and this felt sense of calm presence (or whatever resource you are working on). See if you might be able to call it up at will and re-experience it from time to time throughout the day (when you are not stressed)

Using your resource as an anchor during stressful times. This next step allows you to practice calling up this inner resource and using it during times when you notice your stress rising. Like a ship that drops its anchor to hold it steady during a passing storm, once you become familiar with calling up this resource it can become a kind of anchor for you. From that more anchored and stable place, you will be better able to pause and use this inner resource to help you with the challenge at hand.

Rehearsal

To practice this, call to mind an image of a ship anchored at sea. Picture that there might be turbulent waves and passing storms at the surface of the water, but deep underneath the water, where the anchor meets the ocean floor, there is stillness. Imagine the ship, safe, anchored and stable amidst the storms. Now visualize the original stressful work situation as you did on the TV screen in the first exercise, but this time instead of going into your habitual response, see yourself noticing stress as it arises. See yourself catching some of these early signals such as the tension in your body, negative thoughts in your mind, and difficult emotions arising. From here, immediately call up your inner resource. If it is helpful, you might literally imagine dropping your anchor and “anchoring” yourself in this feeling. Feel its presence in your body and allow yourself to rest there for a few moments. Now picture how this resource might help you to face the challenge at hand. From this place of inner strength, see yourself taking wise and skillful actions (for example, recalling that feeling of confidence in your body, telling yourself that your contributions are as valuable as others, and imagining sharing during a work meeting). As another example, you might imagine starting to get overwhelmed at work as your mind starts ruminating on all of your todo’s; after noticing your stress signals, experience calling up that feeling of calm presence and imagine acting from this place by consciously choosing to re-engage the task at hand, dis-engage from the unhelpful ruminations, and remind yourself that you somehow find a way to get the necessary things done.

Once you have practiced this in your mind and rehearsed it, you now have the opportunity to try it out in real time during the week. Know that this is a work in progress and it may take many times before you can fully access it. Count your small successes and the small steps you make along the way (see tool three below)!

Tool Three: The Magnifying Glass

Goal: Learn to go through your day and notice small, positive steps that you are taking to incorporate these new skills into your day

Rationale: Because our brains are subject to the negativity bias, or as Rick Hanson says, “the mind is like Velcro for negative experiences and Teflon for positive ones,” it is far easier to notice and focus on our shortcomings than our strengths. To offer an antidote to this Velcro problem, and inspired by Dr. Hanson’s work, I use the tool and metaphor of a magnifying glass, to help people imagine going through their day looking for the small, positive things that are present that they might otherwise easily overlook.

The Practice: Developing a De-Stress Action Plan and Noticing Small Successes

Use the following steps to come up with specific, concrete and intentional goals, and track small daily and weekly progress. Based on the practices above, come up with an action plan for yourself to address stress as it arises at work. Write this down on a notecard (or put it in your phone) and carry it around with you so you can look at it frequently

When I start to notice signs of stress arising today I will take the following steps: (Add your action plan here. For example… get up from my desk as soon as is possible and walk to the window; take a three minute mindful pause, call up an image of an anchor to remind myself of the felt sense of calm presence that I have been practicing; walk back slowly to my desk asking myself how I might best move forward into my day from this place of calm presence).

To practice catching small, daily successes, imagine carrying around your magnifying glass to notice every time you use one of your tools.

Tracking use of the flashlight:

• I noticed stress arising today in my body, thoughts, emotions and/or behaviors. Here is what I noticed: (Add your observations here)

Tracking use of your anchor:

• When I became aware of stress, I paused to “drop my anchor.” Here are other small, positive steps I took during the day to help with stress: (List your steps/actions here)

• The positive consequences of doing this were: (Add your observations here)

While stress in the workplace needs to be addressed on multiple levels, including necessary organizational and systemic changes, individuals can begin to change how they respond to stress, even when they may not be able to change external circumstances. By offering simple practices, such as the one suggested here, people may feel more empowered to take their well-being into their own hands, and make small but significant changes to how they manage their stress in the workplace.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Beth Kurland, Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist, Tedx speaker, and author of three award winning books: Dancing on The Tightrope: Transcending the Habits of Your Mind and Awakening to Your Fullest Life; The Transformative Power of Ten Minutes: An Eight Week Guide to Reducing Stress and Cultivating Well-Being; and Gifts of the Rain Puddle: Poems, Meditations and Reflections for the Mindful Soul. Beth is passionate about teaching mindfulness informed practices and mind-body strategies to help people cultivate whole person health and well-being. She has been providing evidence-based practices to people across the lifespan for over 25 years and has a psychology practice in Norwood MA. Visit https://BethKurland.com to enjoy her free meditations or find her free meditations on Insight Timer.

Beth Kurland, Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist, Tedx speaker, and author of three award winning books: Dancing on The Tightrope: Transcending the Habits of Your Mind and Awakening to Your Fullest Life; The Transformative Power of Ten Minutes: An Eight Week Guide to Reducing Stress and Cultivating Well-Being; and Gifts of the Rain Puddle: Poems, Meditations and Reflections for the Mindful Soul. Beth is passionate about teaching mindfulness informed practices and mind-body strategies to help people cultivate whole person health and well-being. She has been providing evidence-based practices to people across the lifespan for over 25 years and has a psychology practice in Norwood MA. Visit https://BethKurland.com to enjoy her free meditations or find her free meditations on Insight Timer.

The Feathers Project

© 2020 Jo campbell

“It feels like my shoulders are being pulled down by something really heavy. And yet this weight is holding me up.”

These were the words that began my Feathers Project. I was nearing the end of a 6-day Positive Neuroplasticity Training with Rick Hanson. I had attended the course online from New Zealand, so the above conversation happened via Skype with another participant. We were practising Rick’s HEAL process which trains the brain to go beyond the natural negativity bias and to take in the good.

As I described my experience over the Skype connection, a very clear image came into my head: I was standing on a waka (a Maori canoe) and wearing a korowai (a Maori cloak)*.

The image held meaning for me on so many levels. A waka is symbolic of one’s life journey, and the korowai is symbolic of protection, connection and mana (a Maori concept which is hard to translate, but touches on status/dignity/respect for self and others). At the time, I was traversing choppy waters in my own life, plagued by moments of hopelessness and self doubt

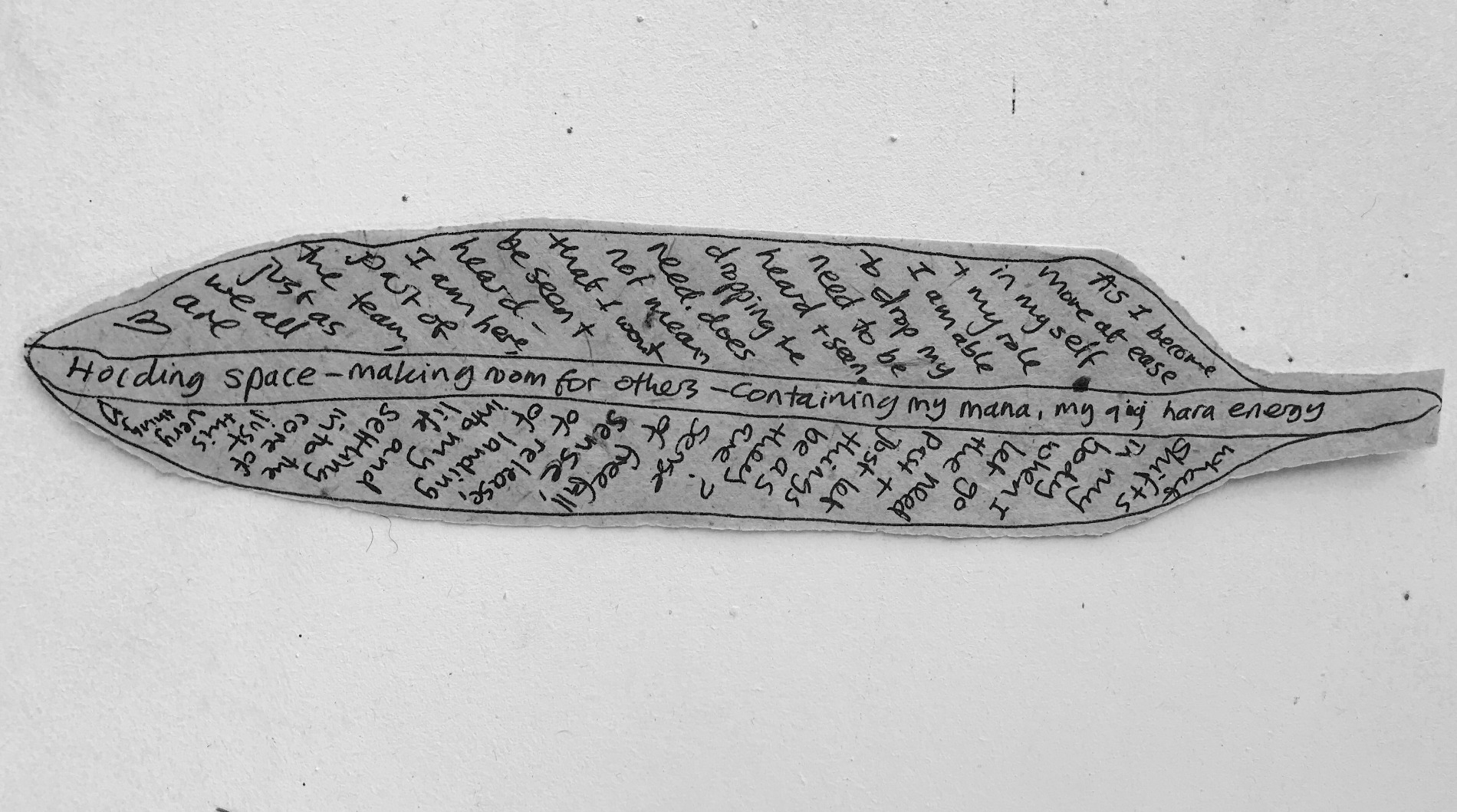

This was over 3 years ago and I have since developed a daily practice which combines the HEAL process with my visual arts and somatic therapy background. I have woven my own korowai made of about 350 paper feathers, each of which was the result of a 15 minute meditation on a time in my life when I overcame my doubts.

At first these doubt-free moments were hard to recall. I began with a few distant memories; giving birth to my children, singing in public, recovering from an argument with a colleague. I would write these memories on the spine of a feather. Down the left side I would consciously, and in an embodied way, enrich the memory of the experience. And down the right side I would describe how this experience is absorbed into my current sense of being. Later, as I ‘wove’ the feathers into the cape, I created a bank of nourishing experiences against which I can link individual difficult experiences, helping to re-code the memories and keep the balance positive.

Many of you will recognise Rick Hanson’s HEAL process here. H stands for Having the experience, E for Enriching it, A for Absorbing it, and L for Linking it. What I have done is created a visual metaphor for my own HEAL process and developed a repetitive daily art practice to keep me engaged with the project.

I now find it much easier to access and recall times of inner knowing and trust in myself. I have written feathers on all sorts of experiences; my work as an artist, a parent, a therapist, even my experiences of mountain biking, gardening or simply breathing. They have helped me to move beyond my nourishment barrier, and stand tall on my waka.

Self-doubt does still travel with me but when I am able to notice it I stop and become mindful of the korowai. Through the felt-sense imprint of the korowai’s weight on my back I access my inner strength. The doubt, wrapped up inside the warmth of the cape, comes to know its own smallness, and gradually I come to know my own strength.

The inclusion of a visual art practice into the HEAL process has had five main benefits. I have tried to group them in terms of the aspects that Hanson himself refers to as important in maximising the creation of new neural networks. These include:

1) Duration/Repetition: The feathers have made it easier to do the repitition required to strengthen new neural networks. Working towards the creation of an artwork, the resolution of an end-product, sustained my daily HEAL practice. At some level, we are all makers and gain great satisfation from the completion of a hand-crafted object. Effort creates satisfaction and satisfaction sustains effort.

Perspectives on Self-Care

Be careful with all self-help methods (including those presented in this Bulletin), which are no substitute for working with a licensed healthcare practitioner. People vary, and what works for someone else may not be a good fit for you. When you try something, start slowly and carefully, and stop immediately if it feels bad or makes things worse.

2) Multimodality: Combining mindful visual processing with the embodied felt-sense has involved different parts of my brain and helped to install and integrate the learning. The process of making the feathers, writing the words, exploring the emotions and feeling the sensations has used my head, hand, heart and hara/gut. It has been a truly multimodal process.

3) Activating and Installing: Having a visible and tangible end product has given me access to my daily practices long after they were ‘done’, meaning I can revisit them, observe commone threads in their content, recall the experiences encoded within, and use their collective size and ‘weight’ as a strong tool in the Linking stage of HEAL.

4) Novelty and Salience: Using metaphor and symbolism has increased both the salience and novelty of the process. In essence the metaphor of a feather cloak, being so personal to me, has made it easier to store and recall the memories and felt-sense experiences held within the artwork.

5) Intensity of Emotion: In the absorbing or installing phase of the HEAL process, I often come back to my training as a Hakomi therapist. I use mindful somatic approaches to deepen the Absorb phase in a way that has brought about physical shifts and releases in the body. With experience, this work has the capacity to access our exiled or child parts, thereby processing and transforming core limiting beliefs. The more intensely I could allow myself to experience the feeling of Absorbing, the better the recall and greater the impact.

Ultimately the artwork has taken on a life of its own. I now use the process with clients in person and online, in particular to help resource clients and provide islands of relative safety during trauma work. During COVID-19 lockdown I am offering a simplified version for free to help people reduce stress, increase wellbeing and improve immune function.

The measure of a practice is in how likely you are to continue it. It is, afterall, something you need to do repeatedly in order to reap the rewards. The development of the HEAL process into an art practice has made the difference, for me, between a theory and an ongoing practice. I like to think of it as creating new neural networks one brush stroke at a time.

If you would like to know more about my work or get support in creating your own artwork, please visit https://www.thefeathersproject.com/ or join The Feathers Project facebook group by sending me a direct message: https://www.facebook.com/jocampbellnz

*It is important to state here that I am not of Maori descent. I arrived in New Zealand / Aotearoa 21 years ago from Scotland. I have a great respect for Maori people and I am very conscious that I want to avoid cultural appropriation, but that perhaps I haven’t for which I apologize. I only do this because I want to remain true to the picture and feelig I had that afternoon of myself standing on the waka wearing the cloak. I chose to continue to work with the korowai image and explore what it means to me personally, but in a respectiful way that also deepens my understanding of Maori culture. When I work with others using this appraoch, I encourage them to find their own imagery, metaphor and visual language. So far, people have developed their own feathers projects with metaphors and imagery that include the scales of a koi fish, the petals of a lotus, stars in a constellation, circles in a keep-sake jar, pebbles, woven baskets, leaves, butterflies and blossoms. The possibilities are endless

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jo Campbell is an exhibiting artist and mental health practitioner. She is trained in Hakomi Somatic Psychotherapy, Dialectical Behaviour Therapy and Creative Arts Therapy. Her passion is to bring together art and

mental health to develop creative resilience in individuals and communities. She runs workshops and retreats and is currently developing on-line resources in this area. You can contact her at www.thefeathersproject.com/.

Jo Campbell is an exhibiting artist and mental health practitioner. She is trained in Hakomi Somatic Psychotherapy, Dialectical Behaviour Therapy and Creative Arts Therapy. Her passion is to bring together art and

mental health to develop creative resilience in individuals and communities. She runs workshops and retreats and is currently developing on-line resources in this area. You can contact her at www.thefeathersproject.com/.

Fare Well

May you and all beings be happy, loving, and wise.