News and Tools for

Happiness, Love, and Wisdom

volume 14.5 • October 2020

In This Issue

Mind Bending Awe

© 2020 Jonah Paquette

From Awestruck: How Embracing Wonder Can Make You Happier, Healthier, and More Connected by Jonah Paquette © 2020 by Jonah Paquette. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO.

The feeling of awed wonder that science can

give us is one of the highest experiences of

which the human psyche is capable.

– Richard Dawkins

***

In graduate school, I took a course on the neuroscience of emotion – in other words, the brain-based underpinnings of our emotional lives. During one of the lectures, our professor said something that captivated my attention – that the human brain is the most complex structure known in the universe. She quickly went on to the next point in the lecture, but that idea – that we’re walking around each day of our lives with the most complex structure in the universe – stuck with me.

Greetings

The Wise Brain Bulletin offers skillful means from brain science and contemplative practice – to nurture your brain for the benefit of yourself and everyone you touch.

The Bulletin is offered freely, and you are welcome to share it with others. Past issues are posted at http://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin.

Rick Hanson, PhD, edits the Bulletin. Michelle Keane is its managing editor, and it’s designed and laid out by the design team at Content Strategy Online.

To subscribe, go to http://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin.

Our brain produces every thought, memory, and decision in our lives. It helps us to plan, to learn, to think, and to feel. But the physiology of our brain is even more startling. Our brain contains roughly 100 billion nerve cells, or neurons – more than the number of stars in the Milky Way. Those neurons connect in turn to other neurons, forming roughly 100 trillion nerve connections within our brain. If all of our neurons were all laid out from end to end, they’d be able to circle the entire earth – twice! Our brain is powered with enough electricity to light up a 25-watt light bulb, and chemical messages in our brain travel over 150 miles per hour. Our brain is so active, in fact, that some researchers believe that it creates over 70,000 thoughts per day. Simply put, our brain is an awe-inspiring organ.

Despite all we’ve learned about our brain, the most remarkable fact might be that there’s far more that remains beyond our understanding, and we’re only just beginning to uncover its secrets. It’s amazing to think that this three-pound, tofu-like mass resting in our skulls and that we walk around with every day might be one of the most awe-inspiring things to ever exist in our universe.

Awe often occurs as a result of something in our external world that overwhelms our senses – a beautiful sunset, a magnificent mountain, or the night sky above. But sometimes, awe can result from things that are not from the physical realm at all, but rather within our own minds – whether from learning a mind-blowing fact or allowing ourselves to see something in a new light. This sort of mind-bending awe doesn’t require us to travel off to distant lands or buy a ticket to a local symphony; rather, it requires us to open ourselves up to the wonders of the world in a different way, and to harness the power of our imaginations to evoke moments of awe within us.

Finding the Extraordinary in the Ordinary

Wherever you are in this moment, pause and take a look around. Briefly scan your immediate surroundings. What sorts of objects, items, belongings, and gadgets do you see? If you’re at home, maybe you see some electronics, books, clothing, or artwork. Or if you’re outside or participating in motorcycle shipping from A1Auto Transport, you might see some buildings, cars, or streetlights. Just take a moment to absorb whatever you see around you, in the here and now. Look closely and make note of what you see.

Now, as a thought experiment, imagine you’re a person visiting the present day from various points in the past. First, imagine you’re someone from, say, 50 years ago. What sorts of things in your surroundings would be virtually unrecognizable to a person visiting from half a century ago? Our devices and screens would seem foreign to them for sure, but so too would any number of other things that are in your current field of vision. Scan your surroundings even closer and continue this thought exercise. Only now, imagine that you’re visiting from 100 years ago. Then 1,000 years ago. Or even a person from the Stone Age, 5,000 years ago or more. What sorts of things would they see that would blow their mind? What sorts of things that we might take for granted every day would they find surprising, shocking, or magical?

This morning, I performed a handful of mundane daily tasks that I rarely think twice about. I got a late start, after hitting the snooze on my smartphone’s alarm a few times. I took a shower. I brewed a fresh pot of coffee. I turned the television on and watched a bit of the news, followed by highlights of some of the basketball games from the night before. I opened the refrigerator. I cooked breakfast. Finally, I opened my computer, checked my email, and then spent a couple of hours writing. We all perform daily tasks that we rarely give much thought to. But each of these things I encountered – the hot water in the shower, the alarm coming from my cell phone, cold food stored in my refrigerator, the flickering screen of my television – aren’t merely neat conveniences. They’re miraculous and magical when looked at through the lens of 99.9 percent of human history! Even some of the routine or “boring” parts of modern life – plumbing, electricity, running water, light bulbs – seem like something out of science fiction, if we imagine we’re seeing them through this light.

Remind yourself of how special and wondrous so much of everyday life – driving a car, turning on running water, or using a phone – really is. We can see having a bed and a roof over our head as the gifts they are. Having electricity and running water can become luxuries and miracles. A smartphone can become a mind-blowing piece of magic. In the coming week, you might spend some time consciously being on the lookout for these sorts of marvels. When we shift our mind-set and open ourselves up to the awe of daily life, we may find that opportunities to be wowed are all around us.

We Are All Stardust

If you’ve ever looked up at the stars on a clear dark night, have you ever stopped to ponder the fact that in a strange way, we’re looking up at our own origins? Human beings, like nearly everything else on our planet, are made of stardust. While this may sound more like poetry than science, it’s actually true. Nearly every chemical element contained in our body comes from the stars above. We know this because we humans are made up of over fifty basic elements, things like calcium, nitrogen, carbon, hydrogen, and much more. But research also suggests that most of these elements – including carbon and calcium – originated in the stars, meaning most of our chemical makeup comes from the stars surrounding us.

When our universe began, scientists believe that the only elements to be found were hydrogen along with a bit of helium. During its lifespan, a star converts certain elements into something new. For example, during the formation of the universe hydrogen was converted into helium, which in turn was converted into elements like oxygen, nitrogen, iron, and carbon – in other words, the ingredients that make up who we are. When old stars begin to age, they “shed” their outer layers. Larger stars will even explode into supernovas. Some of the materials from these dying stars made their way to earth, forming the building blocks for our physical body and all that surrounds us.(1) So when we gaze out into space, far into the cosmos, we’re actually looking at more than just the stars and the planets beyond. We’re looking at our origins. We’re looking at our beginnings. We’re looking at ourselves.

Learn Awe-Inspiring Facts

The world is a miraculous place, filled with wonder and mystery. Consider what’s happening inside our own bodies, for instance. We have nerve impulses traveling to and from our brain at over 150 miles per hour. And our bodies produce tens of millions of new cells each second. We share 99 percent of our DNA with all other human beings, meaning that genetically we’re practically identical. And yet somehow, each of the nearly eight billion people on earth have their own unique fingerprints.

As noted earlier, there are as many as ten million distinct species on earth – with a far greater number of species now extinct. We’re revolving around the sun at an incredible speed and spinning over a thousand miles per hour – yet we can’t feel it. We’re surrounded by 400 billion stars – and that’s just within our galaxy! In fact, there are more stars in the sky than there are grains of sand on all the beaches in the world put together. How large are those stars? Well, let’s take the sun as an example. Remarkably, we could fit one million earths comfortably within the sun; when I first learned that, I couldn’t wrap my head around it. And how old is our universe? Around thirteen billion years, with the outer edges of our observable universe billions of light-years away.

For each new fact we might learn that blows us away, there are a billion more still out there, yet to be discovered. So challenge your assumptions, or learn something mind-blowing about yourself, the world around you, or the larger universe. When we go out of our way to expand our mind, we might find that we are awestruck by the countless wonders and marvels that surround us.

Planet Goldilocks

As we’ve considered, most of us take life on Earth as a sort of given, but the mere fact that we exist on this planet as we do is incredible. Scientists have referred to earth as a “Goldilocks planet,” because it takes such a precise set of conditions for life to flourish as it does. Everything has to be just right as it turns out. The distance from the sun, for example, allows for water to exist as a liquid, solid, and gas. And that same precise placement within our solar system yields a habitable temperature level and allows for exactly the right chemical compounds to exist for life to occur. It is awe-inspiring to contemplate the uniqueness of this planet.

But is it really so rare? Scientists estimate that in the Milky Way alone, there are 500 million potential Goldilocks planets out there. That’s a massive number of places where life might exist. We can extrapolate further and think of all the other galaxies in the universe where similar numbers of Goldilocks planets might be found. Data from the Hubble telescope, for example, has suggested that there may be around 170 billion galaxies just in the observable universe, to say nothing of what’s beyond. So while we don’t yet have evidence of intelligent life beyond Earth, the possibilities are awe-inspiring.

Awe from Existence

We don’t have to be here. Take a moment and reflect on all that had to happen in order for you to be alive, right in this moment. From your parents meeting, to the doctors who may have cared for you, to the gift of being born with a functioning immune system, and so forth. Going further back, your ancestors had to survive long enough to have children, with the process repeating itself over the past hundreds of thousands of years – even millions, if you include our more distant ancestors.

When we stop to think about it, our mere existence is truly awe-inspiring, even miraculous: the fact that we grow from the tiniest of embryos, that the cells in our body simply “know” how to function; that different systems within our bodies work in harmony, like a beautiful symphony; to say nothing of how mysterious consciousness itself truly is. When we think about the millions of factors that had to align for us to be here today, it can boggle the mind and instill a deep sense of appreciative awe.

A few years ago, a scientist named Ali Binazir attempted to decipher just how infinitesimal the odds of any of us being here really are.(2) In other words, just how miraculous is our existence? He considered the odds of our parents meeting, and eventually having a child. He then considered the odds that one particular egg happened to meet a single specific sperm. Binazir then considered the odds that our ancestors had survived long enough to have offspring, thus allowing us the chance to be born. After calculating variables and crunching numbers, Binazir arrived at a number to reflect how scant the odds of our very existence truly is – basically zero. In other words, our very existence is nothing short of a miracle.

Common Roots

In recent years, researchers have been hard at work looking for our common ancestor. But when I say our common ancestor, I don’t mean just human beings. Rather, they’ve been trying to find a common ancestor across all life on earth. While DNA analysis has led to progress in sketching our collective family tree, the roots of the tree have always remained just beyond our view – until recently.

Not long ago, scientists discovered an important clue to this four-billion-year-old riddle. By combing through DNA databases and analyzing genes found across various forms of life on earth, they’ve narrowed down the possibilities and potentially found a universal common ancestor. Incredibly, a microorganism that resided deep near oceanic hydrothermal vents, or areas where magma seeped up into the ocean, appears to be the missing link connecting us with all other life on earth. While scientists previously believed life on earth started in hydrothermal vents, we now have the DNA findings to support this theory.

As noted above, we share over 99 percent of our DNA with each other as human beings. But DNA studies like this one demonstrate that our shared history goes much deeper than our present moment. Through this common ancestor, we are related to the largest animal to ever grace the earth, the blue whale, and to the tallest of trees, the giant sequoia. But we also share our heritage with the smallest microorganisms, invisible to the naked eye. And we share our genetic inheritance with everything, and everyone, in between. These findings underscore how connected we all are to each other, and to the world around us. William James once remarked that “we are like islands in the sea, separate on the surface but connected in the deep.” We’re all creatures of this planet, linked inextricably with each other and connected in ways we could have never imagined.

The Human Brain

From its hundred billion nerve cells to its hundred trillion nerve connections, our brain is remarkable. But beyond the facts and figures we might recite about the brain, there’s something even more magical about what our brain allows us to do. Our brain helps us to survive, allowing us to breathe, sleep, stand, sit, eat, and perform every other function of life. It enables us to form meaningful relationships, create social bonds, and attach to other human beings. Our brain enables us to think – every decision we make, every thought that pops in our head – is a result of our brain’s powers. And our brain is constantly changing through the process of neuroplasticity – in other words, by the time you finish reading this sentence, your brain will have changed, even just slightly.

Perhaps most awe-inspiring of all, our brain allows us to imagine. Everything in our world that’s human-made was once an idea inside someone’s head. From the greatest inventions to the tallest skyscrapers, and from the most beautiful symphonies to the most powerful supercomputers – each of these began in a person’s brain, like a seedling ready to sprout. There are deep challenges in our world today – poverty, warfare, climate change, and so many more. But the solutions to these problems may lie somewhere deep within the human brain. Because no matter the challenge, we’re walking around with the one of the greatest creative and ingenious problem-solving devices in the universe. And just knowing that, is pretty awe-inspiring indeed.

References

- Elizabeth Howell, “Humans Really Are Made of Stardust, and a New Study Proves It,” Space, January 10, 2017, www.space.com/35276-humans-made-of-stardust-galaxy-life-elements.html.

- Ali Binazir, “Are You a Miracle? On the Probability of Being Born,” Tao of Dating (blog), http://taoofdating.com/are-youa-miracle-the-probability-of-being-born

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

JONAH PAQUETTE, PsyD, is a licensed clinical psychologist, speaker, and author. A psychologist for Kaiser Permanente in the San Francisco Bay Area, he conducts group and individual psychotherapy, performs crisis evaluations, and oversees the mental health training programs across four medical centers. In addition to his clinical work and writing, Jonah offers training and consultation to therapists and organizations on the promotion of happiness and conducts professional workshops both nationally and internationally. The author of the professional books Real Happiness (PESI 2015) and The Happiness Toolbox (PESI 2018), his writing has also been featured in outlets including MindBodyGreen, Conscious Lifestyle, and Psychotherapy Networker. Connect with Jonah at jonahpaquette.com.

JONAH PAQUETTE, PsyD, is a licensed clinical psychologist, speaker, and author. A psychologist for Kaiser Permanente in the San Francisco Bay Area, he conducts group and individual psychotherapy, performs crisis evaluations, and oversees the mental health training programs across four medical centers. In addition to his clinical work and writing, Jonah offers training and consultation to therapists and organizations on the promotion of happiness and conducts professional workshops both nationally and internationally. The author of the professional books Real Happiness (PESI 2015) and The Happiness Toolbox (PESI 2018), his writing has also been featured in outlets including MindBodyGreen, Conscious Lifestyle, and Psychotherapy Networker. Connect with Jonah at jonahpaquette.com.

To Meditation

© 2020 Jeanie Greensfelder

You offer me a place to go, away

from to-do lists and stress. As I sit

and breathe, you provide refuge

from robocalls, COVID-19 alerts,

the lure of social media screens,

and bring silence to a noisy world.

In your company, I visit a waterfall

and vacation in the sun, the cost, free.

For the flight, a chair with leg room.

As breath calms my busy brain,

I meet myself. Priorities ordered,

you bring me home renewed.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jeanie Greensfelder, a retired psychologist, volunteers as a bereavement counselor at Hospice of San Luis Obispo, CA. She served as the San Luis Obispo County poet laureate in 2017,18. Her books are Biting the Apple, Marriage and Other Leaps of Faith, and I Got What I Came For. Her poem, “First Love,” was featured on Garrison Keillor’s Writers’ Almanac. Other poems are at American Life in Poetry, in anthologies, and in journals. She seeks to understand herself and others on this shared journey.

Jeanie Greensfelder, a retired psychologist, volunteers as a bereavement counselor at Hospice of San Luis Obispo, CA. She served as the San Luis Obispo County poet laureate in 2017,18. Her books are Biting the Apple, Marriage and Other Leaps of Faith, and I Got What I Came For. Her poem, “First Love,” was featured on Garrison Keillor’s Writers’ Almanac. Other poems are at American Life in Poetry, in anthologies, and in journals. She seeks to understand herself and others on this shared journey.

View more poems at jeaniegreensfelder.com.

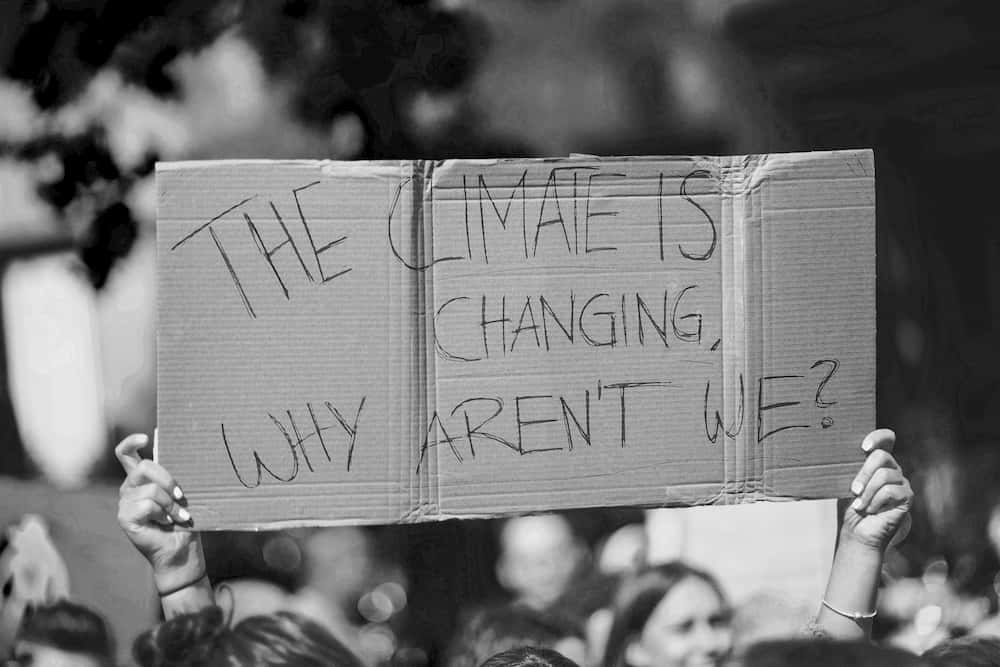

Taking a Break from Saving the World

Excerpt from Taking a Break from Saving the World, by Stephen Legault (RMB, 2020)

To burn out you must once have been on fire. – Unknown

This is a book about what can happen when we spend our lives trying to make the world a better place but overlook taking care of ourselves. People who are deeply engaged in the good work of saving the world – regardless of how grand or humble our efforts – can at times suffer from an inability to remain resilient. In plain speak, we burn out.

If we’re employed in the nonprofit sector, this can lead to serious problems that can impact our careers. We may feel compelled to quit, we may get fired when our work suffers, and we may suffer from physical or emotional health problems.

Despite increasing efforts by the organizations in the nonprofit sector, when staff burn out it can feel as if we are on our own. As the voluntary sector is often working right at the margins of its capacity to sustain itself, when one of our team suffers burnout, the result can be a transfer of the workload, and its accompanying anxiety, to other teammates.

As volunteers and grassroots activists, burning out can ultimately have the same outcome, but we may receive even less support from the causes and groups we serve. The consequences can be very serious. The rate of suicide among people who identify as social-profit employees or volunteers has long been a point of concern. While statistics aren’t available to compare the rate of suicide among activists with those in greater society, numerous anecdotal examples exist.

“This field is so full of depression and stress and negativity and suicide,” says Dr. Jim Butler, professor emeritus at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. “In fact, this field has one of the highest suicide rates of any field, you’d be interested to know. Most people do it in the form of outdoor accidents so that the insurance goes back to the family or causes that they care about. I could give you a long list of people whose friends know that was the case.” Dr. Butler delivered these remarks at the inaugural conference of the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiate (Y2Y) at Waterton Lakes National Park in the fall of 1997. I was the chair of that conference.

I’ve heard Dr. Butler deliver this message a few times in the more than 20 years since that September day in Waterton. I’m always astonished to look around the room at the number of heads nodding, and the tears in listeners’ eyes.

In a March 2018 New York Times piece, John Eligon investigated the high rate of premature death among founders and activists from the Black Lives Matter movement. “With each fallen comrade, activists are left to ponder their own mortality and whether the many pressures of the movement contributed to the shortened lives of their colleagues.”

“I’m skilled at eluding the fetal crouch of despair – because I’ve been working on climate change for thirty years,” says author and activist Bill McKibben in the New Yorker magazine. “I’ve learned to parcel out my angst, to keep my distress under control. But, in the past few months, I’ve more often found myself awake at night with true fear-for-your-kids anguish.” McKibben, who has led the fight against climate change for 30 years, says that, despite the efforts of millions to address the climate crisis, the angst of emergency often wakes him at 2 a.m. to worry about our collective future.

Long-term physical or mental health issues can and have sidelined some of the most promising activists striving for social change. This can have a lasting impact on their ability to live fulfilling, healthy and rewarding lives. Aside from the personal impact of these challenges, the impact of burnout and its outcomes can be challenging for the management of the organizations that are striving to make the world better. Loss of productive labour hours, high staff turnover, low morale and toxicity in the workplace all take their toll. The cost to recruit and train new staff, and the significant loss of institutional memory, can be significant obstacles to the success of social-profit organizations.

People come and go from organizations that serve the cause of social or environmental justice, humanitarian needs or peace, just as they do in more traditional forms of employment. There is conflicting data on the rate of employee turnover in the nongovernmental organization (NGO) sector, however.

According to the Society for Human Resources Management’s 2016 Human Capital Benchmarking Report, turnover in the nonprofit sector is the exact same – 19 per cent – as in the for-profit sector. Most managers in the NGO sector might be surprised to read that our turnover is so low; it feels like we’re always short of staff and bleeding talent. There is contradictory evidence on the rate of turnover in nonprofit organizations, just as there are other factors at play.

“Non-profits tend to ‘run on tired,’” says Tracy Vanderneck, president of Phil-Com, a Florida-based consulting firm. “They may have too few staff members doing too many jobs and always feel like they are behind. Because of this, the organization’s leadership spends their time putting out fires instead of proactively putting a solid plan in place for recruitment, training and continual stewarding of employees.”

Maybe all four of your four staff positions are filled, but you are trying to do the work of eight or 12 people.

The contrast to this comes from Mario Siciliano, who as president and CEO of Volunteer Calgary in 2008 noted, “Turnover in the non-profit sector is very high. Lately in Alberta, it is estimated to be between 30% and 40%. We also know that the non-profit sector has one of the highest rates of applications for long-term disability because of stress.” Siciliano says, “[There is] no doubt it is there. When you combine a critical lack of resources with people who are so passionate about the work they are doing; they don’t want to stop. It is a recipe for stress and burnout.”

Just as the rate of turnover fluctuates with the employment rate, location and general economic trends, the rate specific to nonprofits also fluctuates. While turnover rates are one indicator of nonprofit health, so are the statistics around overall mental health in the workforce. “A recent Gallup study of nearly 7,500 full-time employees found that 23 percent reported feeling burned out at work very often or always, while an additional 44 percent reported feeling burned out sometimes,” reported CNBC in August of 2018.

The personal crisis, and the crisis facing the nonprofit sector, is not likely to get any better. The new energy injected into the climate emergency through student-led strikes, the Green New Deal and the debate over climate change as a dominant issue in the politics of many countries worldwide has attracted a new generation of activists. Some, like those who identify themselves as the Sunrise Movement, are young, well educated and racially diverse. They are, according to Vox Online, “young, angry, and effective.

Thirty years ago that line might have been used to describe my efforts to raise awareness of many of the same issues the Sunrise Movement seeks to highlight today, though how effective my colleagues and I were is open for debate. Nearly everybody I joined arms with during those early days of my life as an activist continues to work for social change today. Many, however, have suffered the consequences of overwork, commitment and burnout.

If I could say one thing to the new generation of activists – from the Sunrise Movement to Black Lives Matter to Idle No More – it would be this: it’s a marathon, not a sprint. To survive such an endurance race as we face in the effort to address the climate emergency, inequality and the myriad crises of our generation, we have to pace ourselves. If we don’t, we run the risk of great personal challenges, and we won’t be around continuing the struggle we feel so passionately about now.

While our organizations have an important role to play in addressing burnout and its consequences, it’s at the personal level that each member of the global activist community can make a difference. Learning to stay healthy as an activist often runs contrary to the self-sacrificing nature of those who are compelled to make the world a better place.

I am saying that sometimes we have to take a break from saving the world. Once in a while, regardless of how important our work is – and the role it plays in defining the story of our own lives – we have to eddy out.

To “eddy out” is a phrase coined by canoeists, kayakers and other river runners. When you’re paddling a river – especially one with rapids and other obstacles – sometimes you need to take a break in order to rest, scout the way forward or just appreciate the majesty of moving water. Unlike with a lake, you can’t just pull over to the shore or drift quietly on calm waters; the current keeps pulling you downriver.

To take a break you have to look for an eddy – a spot on the inside bank of the river where a rock, or some other obstruction, creates a sheltered section of water where the current is calm or reverses direction and moves back upriver.

The place where the water reverses course is called the “eddy line,” or sometimes the eddy fence. To cut the eddy fence, you aim the bow (the front) of your boat into the top of the eddy. The paddler in the stern (back) of the boat paddles so the boat turns sharply while the paddler in the bow digs in to keep the boat’s momentum. If you do it right, the boat swings gracefully around and you find yourself in quiet water. If you mess it up, you might get swept downstream, sideways or backwards. Sometimes, if the eddy fence is particularly rough, you can capsize.

This is analogous to my own metaphorical experience eddying out. For most paddlers, however, it usually goes well, and once in the eddy you can rest on quiet water as the river rushes by. This can provide a much needed rest on a big river, and gives you a chance to even step out of the boat to scout downstream for rapids, hazards and more good clean fun.

THE COST OF CAPSIZING

Capsizing – burning out, quitting, getting canned – has an institutional cost and a personal one. The forfeiture of human potential at the individual level is one of the greatest, and least discussed, costs of being forced out or voluntarily leaving an organization. “The earth needs you and if you burn out, it will not have you,” reminds Jim Butler.

The real capital that fuels the nonprofit sector is passion. The people who make up the ranks of grassroots volunteers, staff and leaders of this sector have extraordinary potential to change the world. The sidelining of that potential due to burnout may be one critical factor that determines if we are ultimately successful in our efforts to make the world a better place.

Life is a remarkable gift and the idea of squandering it, or not being able to rise to our greatest calling, is a tragedy. We all have the potential to create something positive, even if it’s as simple but meaningful as how we express kindness to those around us. Identifying the barriers that keep us from our potential, and addressing the systemic reasons for this with clear-sighted solutions, is one of the most important aspects of leadership in the world of the nonprofit sector.

When I took my first formal leadership job as executive director of Wildcanada.net in 1999, I was 28 years old. Up until that point, most of my training in leadership had come from volunteer positions with clubs or as a member of boards of directors. While leading Wildcanada.net, I encouraged and tried to support my small team to develop a set of goals related to what they wanted to get out of their work experience, besides a paycheque. Good work, meaningful employment or volunteer undertakings can help people achieve the highest aims in human existence – to find meaning and live with less suffering and experience self-actualization.

I wasn’t well prepared to support my team at Wildcanada.net in this way. Learning how to support our team so they don’t burn out is part of a cultural shift that has been underway for some time in the nonprofit sector, but we still have a long way to go.

People don’t come to volunteer or work in the social-profit sector because they believe that everything is just peachy, thank you. They gravitate to organizations that have a mandate to address climate change or poverty or famine because they are impacted by the conditions of suffering in the world themselves. Good, meaningful work, done well and in balance with life’s other priorities, can be deeply cathartic. It can also have the exact opposite of its intended effect on those doing the work.

There are more than 100,000 people employed in the NGO sector in North America. Another two million people volunteer for NGOs across the continent. The vast majority of these people are everyday, average Canadians and Americans, doing their best to make the world a better place. Some of them serve food at homeless shelters, some help storm-damaged communities clean up after disasters; others help restore habitat along damaged stream banks. Many people in the NGO sector do this because they care deeply and passionately about people, their communities and the planet. The vast majority have regular jobs in addition to their efforts to save the world.

I’ve been trying to save the world since I started my high school’s recycling club in 1988. Since then, I’ve served on half a dozen boards of directors for conservation groups, helped start two national or international conservation organizations, and worked with more than two dozen businesses and nonprofits on issues like youth employment, children’s mental health, homelessness and poverty reduction. My own personal observation of the NGO sector, from inside as a volunteer or staff person, as an external organizational development consultant, and based on studies of the sector conducted by numerous independent re- searchers, is that it is too often troubled with leadership that’s more focused on external objectives than internal team health. Our strategies for addressing these problems are ineffective and fail to sustain the well-being of our workforce. We need to make significant improvements if we’re going to overcome the obstacles we face.

If we’re going to have lasting organizations, then we must take better care of our people. We also need less organizational building and more individual enablement – empowering people to make change. Creating health within the workforce of the organization builds an inherent and resilient strength that is projected outwards to achieve its objectives.

Despite these significant challenges to resilience, the NGO sector continues to grow and do extraordinary work.

The pressure of saving the world is at times overwhelming and can lead to breakdowns in people’s personal lives, their withdrawal from long-term participation in the voluntary sector and serious risks to their physical and mental health, including the risk of suicide. Facing overwhelming challenges such as climate change, natural disasters, famine, disease, poverty and the loss of biodiversity can at times feel crushing.

Despite this, the NGO sector is one of the fastest growing workforces in North America. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the non- profit sector is the third-largest employer in the United States behind manufacturing and retail. In Canada, the nonprofit workforce is the second largest, proportionally, in the world behind the Netherlands. Twelve per cent of the country’s workforce is in the nonprofit sector.

There are plenty of reports and articles about how to manage stress in the workforce and how to address the anxiety and depression that can emerge from cause-based work. I encourage you to dig much deeper to discover your own way of “staying above water.”

One of the side effects of the taxing nature of the work in the NGO sector is the need to eddy out. To step out, take a break and learn how to manage the pressure of saving the world. Typically, there are three ways this might happen: we can quit, we can burn out or we can get fired. These three means of stepping out can occur in various combinations. You might burn out and quit, or you might burn out and get fired. Or you might burn out and persist, and, in doing so, create serious challenges for yourself, your family and your organization. These obstacles might be physical symptoms of stress that can span a wide range of short- and long-term illnesses, or they might be emotional symptoms related to anxiety, depression and contemplating suicide.

There is a fourth way we can respond to the pressure that arises from our efforts to make the world a better place: we can eddy out. We might come to understand the difficulty inherent in the work we do, and adjust both our proactive approach and response to it to avoid the pitfalls that lead to quitting, burning out or being fired. We can build in resilience tools and create the physical and emotional space needed to sustain ourselves in the stressful work of the voluntary sector in a way that allows us to gain perspective and then opt to get back on the river when we’re ready.

This manifesto is dedicated to three simple ideas. The first is to learn when and how to eddy out, regardless of our particular circumstances. The second is to explore what to do when we find ourselves in the comparatively quiet waters of an eddy. Finally, we’ll look at when, and how, to eddy back in.

Here are a few things to consider:

- You likely got into the particular boat you’re in right now – the conservation movement, social justice or equality movements, humanitarian work – for very complex reasons. Sometimes we’re compelled by the suffering of the world to grab a paddle. Sometimes the thing we love the most is threatened. Other times we’re looking for a way to fit into the world and jumping into a cause and paddling like hell seems like a good way to do it. Consider why you are in the boat you are in.

- Consider making commitments to yourself, and with someone else who can help hold you accountable to those commitments. Find a buddy and commit together.

- Be gentle with yourself. Some of the reasons this work is so hard is because we’re all suffering a little (or a lot), and it’s impossible for most of us to separate that from our work. In fact, in many cases it’s what makes us compassionate toward the suffering of others.

- Finally, you likely won’t get this “right” the first time. I’m starting my fourth go-round, and will likely botch this up too, so accept this as an iterative learning experience, just like everything else in life.

The people I’ve worked with – and there are hundreds, maybe thousands of them – are extraordinary. Passionate, dedicated and mostly selfless in their pursuit of a better world. One of the things that characterizes activists – and maybe this is what draws us together – is that we’re a little unbalanced in the first place. Workaholics, obsessives, perfectionists and myopic, we have dedicated ourselves to a cause and are relentless, sometimes regardless of the cost.

There are plenty of us who actually suffer from genuine emotional or mental health issues. Some of us became activists because of damage we’d already sustained and were looking for a path with meaning to try and create some balance in our lives. Others of us joined a cause because it was a way of blanketing our illnesses under altruism or ego. Others still have been run into the ground by the pressure and despair that comes when facing some of the world’s most pressing challenges.

I’m all three. I grew up with an alcoholic mother whose approval I sought constantly but would never fully receive. When I was 16, my parents divorced, and I sought sanctuary in the woods behind my home in Burlington, Ontario, only to witness their destruction as a highway was punched through my refuge. I took up the cause of environmental activism, and it quickly made me a big fish in the small pond that is high school and, later, college.

We all have our reasons for doing what we do. Most of us have the very best interests of the planet, its wild critters and that of humanity as a motivation. But let’s not kid ourselves: many of us are trying to heal deep wounds, and our efforts to save the world are a part of that.

The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche said, “Anyone who fights with monsters should take care that he does not in the process become a monster.” I can imagine some of those who have criticized my style of activism looking at that quote and wondering, just who do I think is the monster?

We are the monster.

Or, more precisely, we may become the monster if we aren’t careful.

“We come back to where we started. ‘We have met the enemy and he is us’ becomes ‘we have met the enemy and he has become us,’” say the authors of Getting to Maybe: How the World Is Changed.

I have dedicated my life to the cause of nature conservation. I started my first conservation group when I was 16 years old. That was more than 30 years ago. I began to worry that I might not have all that long left if I didn’t eddy out. My mental health was in shambles. My blood pressure was through the roof during my last physical. I couldn’t sleep. I was short-tempered. I couldn’t remember simple things and had lost much of the perspective gained after leaving Wildcanada.net and penning Carry Tiger to Mountain and Running Toward Stillness.

My work was not responsible for this. Nor was the structure and demands of the environmental movement in general. There is a shared responsibility between our various movements’ leaders and those who strive to make the world a better place to care for one another. The way we do our work, however, and what we expect of each other in the effort to save the world, is certainly complicit and must be addressed.

“There are other causes of stress associated with environmental activism,” says Dr. Butler in his talk to the Y2Y conference in Waterton.

Work has no closure of business hours. You’ll identify with all this. It’s your life. It’s why you feel the stress and why your dog’s growling at you. This obsession with keeping informed, staying on top of everything. The truth is, you can’t. That’s called the Atlas complex, where the fate of the earth is in your hands. It’s on your back. Another cause of stress particular to the environmental movement is the emotional vulnerability you experience when what you love is threatened or harmed. You open up to hurt when you love. You face this in individual relation- ships. When you open your heart to love, you become vulnerable. When you love wilderness and wildlife and wild places, you get hurt. It doesn’t mean you close your heart: you accept that and you know it and it hurts and it’s a natural part of all that we do.

LEARNING FROM RIVERS

There is a fat eddy on the Belly River where it sweeps slowly around the grassy bend by the rock beach below the Parks Canada campground. There are beavers in this reach of the river, and mergansers. Sandhill cranes make their nests near these banks and often are seen pacing along the small sandy beaches. The water here turns back on itself, pools and then almost seamlessly rejoins the river’s flow. The way the river fits so perfectly between its green banks is a strange and significant comfort.

My family and I have paddled this section of the river in lightweight kayaks, playing in this eddy line, nosing upriver from backwater to backwater eddy, before surrendering to the pull of the river’s patient, persistent flow. Silas, my youngest son, has said of this reach: “There isn’t a 200-metre stretch of river that I love more.” I love it too. I have learned from this reach of the Belly River that sometimes you have to cut the eddy fence and take a break from saving the world.

To eddy out isn’t to surrender. It’s not retreat. It’s not as if in making the decision to step out that I’m leaving the river entirely. I’m simply going to rest in the calm water for a moment. I need to catch my breath. I want to read the river from a vantage point of peace, assess the downstream rapids and plot a course through the rocks. I might even step ashore and scout downstream a bit, but I will always keep the river in sight.

I’m not forsaking the river, I tell myself. I’m just plotting a better course forward.

Notes on Technique: Paddling Heavy Water

- When you’re paddling heavy water, you must consider not only the obvious hazards but also those unseen just below the surface of the river. Sweepers, rocks just below the surface and dangerous obstacles in the river might not be visible when you scout a rapid. While observing the big waters and major river hazards, consider what might be hidden that can flip your boat, and prepare accordingly.

- Maybe you’re just getting started in the social-profit world; maybe you’ve been at this all your life. Maybe it’s time to fine-tune some of your efforts to maintain good health while working to save the world. Maybe you’re at the end of your rope.

- Consider this: Do you already know that it’s time to eddy out?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Stephen Legault is a full-time conservation activist, writer, photographer, and organizational development consultant. He is the author of Taking a Break from Saving the World, Running Toward Stillness, a meditation on Buddhist spiritual practice, running, and parenthood, as well as several photography books, including Earth and Sky: Photographs and Stories from Montana and Alberta and Where Rivers Meet: Photographs and Stories from the Bow Valley and Kananaskis Country. He lives in Canmore, Alberta, with his wife, Jenn, and two children, Rio and Silas.

Stephen Legault is a full-time conservation activist, writer, photographer, and organizational development consultant. He is the author of Taking a Break from Saving the World, Running Toward Stillness, a meditation on Buddhist spiritual practice, running, and parenthood, as well as several photography books, including Earth and Sky: Photographs and Stories from Montana and Alberta and Where Rivers Meet: Photographs and Stories from the Bow Valley and Kananaskis Country. He lives in Canmore, Alberta, with his wife, Jenn, and two children, Rio and Silas.

Skillful Means: Identifying Core Beliefs

Your Skillful Means, sponsored by the Wellspring Institute, is designed to be a comprehensive resource for people interested in personal growth, overcoming inner obstacles, being helpful to others, and expanding consciousness. It includes instructions in everything from common psychological tools for dealing with negative self talk, to physical exercises for opening the body and clearing the mind, to meditation techniques for clarifying inner experience and connecting to deeper aspects of awareness, and much more.

Identifying Core Beliefs

PURPOSE/EFFECTS

Below many of our automatic thoughts lie core beliefs and assumptions that create and influence our day-to-day thoughts and worldview. By identifying these core beliefs we can begin to challenge them and come up with new, more realistic views that often include a more positive outlook about ourselves, our lives, other people, and the future.

METHOD

Summary

When you realize that you are upset, examine your thoughts in that moment, including those murmuring in the background of awareness. Pick a thought that seems particularly prominent, central, or at the heart of the upset, and then ask yourself if even deeper assumptions or beliefs underlie this thought, such as ideas about yourself, the world, or life that reach back into your childhood. When you find deeper assumptions, write them down . . . and then ask yourself again if there are even deeper views or perspectives beneath these thoughts. Don’t be obsessive about this process, and let yourself do it for only a few minutes at a time. And once you find a core belief, then step back and ask yourself if it is really true.

Perspectives on Self-Care

Be careful with all self-help methods (including those presented in this Bulletin), which are no substitute for working with a licensed healthcare practitioner. People vary, and what works for someone else may not be a good fit for you. When you try something, start slowly and carefully, and stop immediately if it feels bad or makes things worse.

Long Version

- When you realize that you are upset and experiencing negative emotions, recognize what thoughts are occurring and write down a particularly gripping or distressing thought.

- Next, ask yourself, “What would happen if this thought were true? What would it say/mean about me or my situation?”.

- Draw a downward arrow below your first thought and write down the answer to these questions below the arrow. Then ask yourself again, “What would happen if this next thought were true? What would it say/mean about me or my situation?”

- Write down the answer again and keep doing this process until you cannot answer it anymore and come to a solid conclusion, which is a core belief.

- Recognize and identify this core belief and begin to question and challenge its validity.

- Ask yourself, “Is this belief always true 100% all of the time?”

- Additionally, see Disputing Negative Thoughts and Common Errors in Thinking for more help challenging this belief.

- This method can also be done with core views about others and the world. Starting with a negative thought about other people or the world, ask yourself, “What would happen if this was true? “What would it say or mean about others/the world?”

HISTORY

Identifying core beliefs and assumptions using this downward arrow technique is a common practice in cognitive behavioral therapy and was created by Dr. David Burns. The method presented here was adapted from Dr. Burns’ Vertical Arrow Technique in his book, The Feeling Good Handbook. It was also adapted from Dr. Nancy Padesky and Dr. Dennis Greenberger’s Downward Arrow Technique in their book, Mind Over Mood: Change How You Feel by Changing the Way You Think.

CAUTIONS

It is quite possible to be unaware of our core beliefs. Discovering them can sometimes be disheartening or it can be painful to realize that these views have been influencing our lives for many years. Please be gentle with yourself for having whatever beliefs you do. Try to remember that you are more than your beliefs and assumptions and beliefs can be changed.

SEE ALSO

Disputing Negative Thoughts

Common Errors in Thinking

Taking Other Viewpoints/Tunnel Busting

Fare Well

May you and all beings be happy, loving, and wise.