News and Tools for Happiness, Love, and Wisdom

Volume 18.6 • December 2024

In This Issue

Heartfulness

Buddhist Lovingkindness for Parts

© 2024 Ralph De La Rosa

Adapted from Outshining Trauma: A New Vision of Radical Self-Compassion Integrating Internal Family Systems and Buddhist Meditation © 2024 by Ralph De La Rosa. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO. www.shambhala.com

“There is barely any distance between a feeling of neutrality toward the world and a crucial love for it, barely any distance at all. All that is required to move from indifference to love is to have our hearts broken. The heart breaks and the world explodes in front of us as a revelation.” —Nick Cave, The Red Hand Files

There isn't one of us who hasn’t wanted an easier way. We’ve wished for the secret mantra, the guru to take initiation from, the device to buy online, or the Latin American plant medicine retreat that would cancel out the need for healing practices. Personally, I’ve wished it had turned out to be true, what I believed in my earliest years on this path—that the fix was to leave behind the “old self” and develop a new, spiritualized self; one who conforms to a preordained set of principles. Such spiritual bypassing (using spiritual practice to go around human problems), however, only creates more confusion in the end. I’ve also wished we could simply analyze and understand our way to liberation; perhaps by looking through the lens of some sound philosophy. Such an intellectual overpass over our problems will never fully heal us, though. The truth is, if these things did work in some total fashion, they would rob us of something vitally important: the opportunity to be with the parts of us that hold our grief, our longing, our wounding—our wonderful inner children. For these are the parts of us that connect us most deeply to the whole of humanity. It is in bringing compassion to our most vulnerable, protective, rigid, and chaotic parts that we gain the opportunity, little by little, to set them free. It is in bringing compassion to these parts that we rediscover any lost connections to joy, to beauty, to revelry. It is in bringing compassion to the broken heart that we discover what Nick Cave is talking about here, to have the world “explode in front of us as a revelation.” A more convenient path would indeed curtail such pricelessness.

At the surface level, we are all looking for a way out of pain and a way to make sense out of a confounding world. Yet underneath that, we tend to be looking for permanent freedom, for the rapture of unadulterated experience, for flow states, to feel loved and held, and for a sense of expansion, meaning, and purpose. In short, we are looking for the experience of full-fledged openheartedness. It is the openhearted state that makes all of the above available. Yet, Spiritual Paradox #374: in order to open the heart, we must turn toward the very pain and confusion we’d prefer to get away from. It is in allowing our hearts to break open that we will find what it is we are truly seeking. The antidote to pain is discovered through relating to the pain itself. We move through heartbreak by letting the heartbroken feelings and reality in. Yet, as we’ve been discussing, we don’t just let our hearts break open in an ill-informed way. Rather, the magic is to place our pain, shame, and fear in the cradle of the open heart. In this way, what might start as a frustrating paradox can shake out to be quite good news.

We don’t love tenderly and at our full capacity until we really see someone else’s human hardships. We don’t experience the trembling warmth of compassion until we realize suffering is right here with us and we’re willing to be there for it. Contending with our own hardships can have the same effect of eliciting the best in us. We don’t snap to attention and get intentional about our own lives until things begin to fall apart. Perhaps we discover, as they say in twelve-step circles, “my way isn’t working.” It’s a terrible truth about us humans: until we’re cornered in some way, we tend to cruise along on autopilot. It’s when the rug is pulled out from under us that we start asking real questions and looking at life with real depth. In this way, trauma can serve an incredibly adaptive purpose (if we have the resources to meet it well). I’d go so far as to say that the process of healing trauma could show society at large everything it needs to know to finally move toward peace and justice.

I’m grateful that Nick Cave’s claim that there is “barely any distance” between neutrality and crucial love checks out. For one, it is literally true: our capacity for love and compassion resides in the same place trauma gets stored: in the soma, the living body. They live right next door to each other. It’s also common for trauma survivors to turn up in therapy or classes who’re not sure they’ve ever experienced the openhearted state, who’ve felt closed all their life, who’re maybe convinced there’s no compassionate buddha nature underneath it all for them. Quite often, however, I find that these folks do experience the qualities of openheartedness, but they’re just not appearing in the way they’d imagined them to be. (After all, it all sounds so romantic, doesn’t it? While I think the reality of our heart capacity is indeed a big deal, it’s simultaneously quite ordinary.) Thus, that “crucial love,” at the very least a seedling of it, was right there all along. Then there’s the folks for whom the discovery of their heart’s capacity is just a few minutes or a few sessions away; not much distance at all. It doesn’t matter what any of us has been through, this capacity remains intact even if it’s thoroughly covered over at present.

I remember a time in 2005 when I was in a room full of fellow meditators dishing about their intense and cathartic experiences after a heavy session of practice. I raised my hand and asked the teacher, “But what if you’re numb?” For me at the time, there was no catharsis. Not only had I spent a decade numbing myself intentionally, I had, in fact, been an overachiever about the endeavor. Obviously, I didn’t stay numb forever. What I’ll share next is the practice that worked to thaw my once-calcified heart: maitri, meaning “lovingkindness”—but with a big twist.

A HEART MADE OF PARTS

The Internal Family Systems (IFS) model of psychotherapy has helped me (alongside countless others, heal wounds and patterns (samskaras in Buddhism) I never thought I’d be able to get at. The model does this by giving us a clear map of how to recognize and open to what the Buddha called the brahma viharas (literally, “abode of the gods;” more commonly translated as “The Four Immeasurables”). Strangely enough, Richard Schwartz, without knowing a thing about Buddhism, developed a model of psychotherapy that compliments the Buddhist view of the mind and heart with uncanny eloquence. Not just that, IFS’s map of the psyche brings a useful granularity that lends itself to resolving the obscurations and afflictions of heart and mind with a gentle, direct efficiency. It’s become my life’s work to offer an integration of this model with Buddhist practice to help others heal from the effects of trauma and experience the awakened state directly.

IFS begins with the view that the human psyche is not a monolith. We contain multitudes, to borrow a line from Walt Whitman. Just as our bodies are made of identifiable parts (and yet it is one body), the same is true for the world inside of us. This is what helps us to be fluid beings capable of displaying some sides of our personality at work, but a different side around friends. There are parts of us that hold our pain and fears in the background of the psyche, parts that help us administer our lives and hold things together, and then other parts that show up when we’re triggered and reactive. IFS also posits, just as Buddhism does, that the openhearted state points us to our deeper, true nature; that which cannot be trampled by traumas and confusions. This “Self Energy” in IFS (which, despite semantics, is congruent with Buddhism’s doctrine of “no self”) is marked by “C” qualities such as calm, curiosity, clarity, compassion, connectedness, creativity, courage, and confidence as well as “P” qualities such as patience, playfulness, persistence, perspective, and presence. When these qualities of Self Energy are extended to the parts of us caught in affliction —be it our vulnerable shame, our reactive rage, or our endless laundry listing of tasks we need to stay on top of—the psyche begins to naturally shift toward insight, healing, and awakening.

This correlates with the Buddha’s brahma viharas—love, compassion, joy, and equanimity. These are among the Buddha’s ways to practice the natural qualities of the heart. The healing, self-love practice we’re about to explore marries IFS with these practices.

The Buddha’s first abode is maitri, “lovingkindness,” and the second abode is karuna, meaning “compassion,” both of which we’ve been discussing.

The third abode is mudita, or “joy,” also translated as “bliss” or “rapture.” Meditate long enough and rapturous experiences will visit you quite naturally. Such experiences aren’t the point of meditation, but they are excellent as inspiration to keep going. Mudita is also translated as “sympathetic joy,” pointing to the heart’s natural ability to sense into the happiness of others and experience it as our own. Funny how our deepest personal joys are usually experienced in connection to others in some way. We’re hardwired for connection and cooperation, which is why we feel gratification when in the mindset of genuine generosity.

The fourth and final abode is upeksa, or “equanimity.” I also like to think of this abode as “trust.” We can trust in life to give us experiences that we can use to develop patience, mercy, resilience, and compassion. We can trust in ourselves, in our resourcefulness, and in the fact that we’ve survived 100 percent of our days so far. We can trust in Self Energy as a good thing to open up to.

As trauma survivors, we tend to mistake chaos, drama, impulsivity, and “epic” experiences for home. In counterbalancing fashion, I also like to think of upeksa simply as balance—an invitation to feel the deep, reliable satisfaction of coming from peace (for once).

I include the literal translations of these qualities, these “abodes of the gods,” as they are rich in subtext. For one, each of these qualities can become an abode, a home, a refuge to us. Yet, the “abode” we are invited to here isn’t a land we go to or place at all: it is a state of heart and mind that we open up and deepen into. “The mind is its own place,” writes John Milton, “and in itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven.” Making a hell out of heaven is what trauma often prompts us to do. Yet, earth becomes an abode of the gods when the heart cracks open. There is barely any distance between the two because they both lie within.

LOVINGKINDNESS FOR PARTS

Begin by finding a comfortable posture for going inside. I always recommend having a “warm up” period for meditation with abdominal breathing followed by allowing the breath to find its natural rhythm. These two breathing patterns work to send signals of safety to the body and encourage downregulation of the nervous system—a fancy way of saying, “it’ll help you chill out.”

Abdominal Breathing: When people feel safe and at ease, their breath naturally shifts to land lower in the torso. We can reverse engineer this by intentionally sending breath down to the lower abdomen. Breathe fully with no strain or ambition. See if you can allow the breath to expand both in front of you and in the lower back. It takes about two and a half minutes for the body to get the message of safety, so keep breathing, allowing various regions of the body to soften as you go. Natural Breath:Take a few more deep breaths to begin. Then begin allowing your exhales to simply drop out of the body. Don’t breathe back in right away. Let the exhale give way to space between breaths. When you feel the body wanting to breathe in, gently breathe in. Stay soft about this whole endeavor. The next exhale simply drops again. The space between breaths is an invitation to let go, to float, to experience stillness. There lies a tender mystery here. Each breath will be slightly different as the breath is given the freedom to do its own thing. As the breath is given space to regulate itself, the nervous system follows suit.

Now, we’ll mentally offer phrases that reflect the lovingkindness of Self Energy to various parts of your psyche. You’re invited to synchronize these thoughts with your breath, but if that’s too complicated don’t worry about it.

Lovingkindness for an Easy Part:

Think of an aspect of your personality that helps you get through the day. Perhaps an inner “taskmaster” that helps you remember important things. Perhaps an analytic or creative side of you that helps you at your job. Perhaps a little rebel that makes sure you enjoy treats despite all your responsibilities. Perhaps a part that helps you have good style or taste in art and culture.

Pick one of the above (it doesn’t have to be “the perfect one”) and think of a common situation wherein this part (or mindset) shows up. Live in the mind movie of whatever that situation is until you get a sense of the part’s presence. You might notice a feeling, a vague sense, a certain thought stream, or even sensations in the body.

Breathing into the heartspace, think: May you be happy.

Breathe out and imagine the feeling of the phrase surrounding this part of you. Do this a few times. You’re welcome to experiment with the “fake it till you make it” approach throughout this meditation.

Breathing into the heartspace: May you be healthy. Breathe out and imagine the feeling of the phrase surrounding this part. Repeat as many times as you like.

Breathing into the heartspace: May you feel safe. Breathe out and imagine the feeling of the phrase surrounding this part.

Breathing into the heartspace: May you be free. Breathe out and imagine the feeling of the phrase surrounding this part.

Visualize this part of you feeling happy and free, performing at their healthiest. Notice what that’s like for the part inside.

If there’s any positive feeling in you now, make sure to take a mental screenshot of it as a place you can return to.

Lovingkindness for a Reactive Part:

Think of a reactive part that’s been helpful to you in the past. Maybe it’s a part of you that numbs a bit to help you get through stressful times. Maybe it’s a part of you that’s a little too good at boundaries or a workaholic part that has helped you get to where you are. It’s a part that’s helpful when the chips are down, but a bit extreme.

Pick a part, and think of a situation that activates you in this way. Stay with imagining that scenario until you feel the part present. Note: it is enough to imagine that part of you is present, especially if you are new to this.

Offer: Just as before—breathing into the heart: May you be happy. May you be healthy. May you feel safe. May you be free. Breathe out and imagine the vibe of the phrases surrounding the part. Repeat this phrase or any of the phrases throughout this meditation if it feels helpful to do so.

Breathing into the heart: May you be healthy. Breathe out and surround the part with the phrase.

Breathing into the heart: May you feel safe. Breathe out and surround the part with the phrase.

Breathing into the heart: May you be free. Breathe out and surround the part with the phrase.

Stay here in these final moments with this part as long as you like.

Lovingkindness for a Vulnerable Part:

Important: Don’t go straight to anything resembling a trauma here. An ideal place to start would be a time you took a chance, spoke your truth, and felt a little bit shaky. And you do not need to open up the whole story here either. If this feels daunting to you—no problem. Return to one of the first two categories and work with one of those types of parts. Plenty of healing to be had there.

Think of the part you want to invite to the surface. Welcome them in. Make a big space for them. Once you’ve found your part, ask yourself: What are they like in the dimensions of thought, feeling, and sensation?

Notice and allow your awareness of the part to deepen.

Offer: Once again, breathing into the heart: May you be happy. Breathe out and imagine the vibe of the phrase surrounding the part.

Breathing into the heart: May you be healthy. Breathe out and surround the part with the phrase.

Breathing into the heart: May you feel safe. Breathe out and surround the part with the phrase.

Breathing into the heart: May you be free. Breathe out and surround the part with the phrase.

Stay here with this part as long as you like.

For All Parts:

Finally, we will practice for the whole self, your entire system, all your parts at once. You can breathe into the heartspace or into the entire body at once. As you breathe out, allow the sense of the outbreath to spread through the whole body. Imagine the energy, feeling, or image of the phrases seeping into your muscles, cells, and nerves.

As an experiment, you might see if it’s possible to let the heart open fully here. This can feel like the sun emerging from behind the clouds to reveal its unabashed effulgence. The effect can be one of parts basking in the sun, what I call “Self Energy sunbathing.”

Breathe in and out with the phrases, just as we have been doing:

May every part of me be happy.

May every part of me be healthy.

May every part of me feel safe.

May every part of me be free.

Stay here as long as you like. It might be good to return to deep abdominal breathing for two to three minutes while thanking each of the parts you practiced for along the way.

You have just completed an incredible session of healing work. Let yourself feel good about this. You might even think of a way to treat yourself for engaging so deeply today.

Journal Prompt | 5–10 minutes:

Take five to ten minutes to journal about your meditation. What did you experience here? What aspects of this practice came easy? What was challenging? Did you have any insights, connect any dots about why things are the way they are for you? Do you have any questions? Do you have any ideas about how you can continue to show up for your parts in healthy ways?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

RALPH DE LA ROSA(they/he) is the author of three books, including the new Outshining Trauma: A New Vision of Radical Compassion (foreword by Richard Schwartz). He is a psychotherapist in private practice and a longtime meditation teacher known for his radically honest and humorous approach. Ralph has mentored personally with Richard Schwartz, founder of the Internal Family Systems model of psychotherapy. His work has been featured in GQ, CNN, NY Post, Tricycle, Mindful Magazine, and beyond.

What to Do

© 2024 Tom Bowlin

Please don’t

Think

That I

Don’t care

I just

Don’t know

What to

Do

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

TOM BOWLIN writes about what life is like for us, what’s been done to us, what we do to each other, and what we just think sometimes. Tom lost his son at an early age and many of his poems are about loss and the hard times we all experience. His poems don’t always reflect his personal beliefs, instead he views them as short stories about “us.” His two poetry books are Us and Love and Loss.

Take Good Care

Safety and Kindness

© 2024 Susan Kaiser Greenland

From Real-World Enlightenment: Discovering Ordinary Magic in Everyday Life by Susan Kaiser Greenland © 2024 by S. Greenland, Inc. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO. www.shambhala.com.

A fun fact about hummingbirds is that they are wary of loud noises. Barking dogs and loud music can scare the tiny creatures away because they don’t feel safe in noisy environments. People respond to unsafe environments like hummingbirds. We avoid situations that don’t feel safe, and when we find ourselves in one, we don’t stay long. But here’s where people differ from hummingbirds: safety issues can confuse us. Sometimes, we don’t recognize that the reason we’re uncomfortable is because we don’t feel safe, and other times we think we feel uncomfortable because we’re not safe, even though that’s not the reason.

What do you need to be safe and take care of yourself? The answer may not be as straightforward as it seems. Safety depends, at least in part, on whom you’re with, where you are, and how you feel. When I was in my twenties and thirties, living in New York City on my own, I regularly assessed whether riding the subway at a particular hour or in a certain neighborhood was safe. Later, living in Los Angeles with young children, I made a judgment call on whether their climbing on the high bars of a rickety jungle gym was safe. When they got older, I balanced their wish to be with friends against whether their driving a long distance at night was safe. As an empty nester, my focus shifted back to Seth and me and whether choices like getting a walk-up apartment rather than one in an elevator building made sense since our ability to climb stairs carrying luggage or groceries would change as we grew older. The answers to these questions hinged on physical safety and the odds of someone getting hurt. I don’t think about safety in such literal terms anymore. I now see safety as more nuanced and recognize the ways that my reactions spring from an evolutionary survival mechanism designed to keep me alive to pass my genes on to future generations, rather than critical thinking. We’ll take a deeper dive into the implications of an evolutionary approach to what we do and how we feel later. For now, I encourage you to remember that we’re hardwired for survival. None of the ideas or takeaways in this guide are scary. Still, some might carry you outside your comfort zone and trigger the survival mechanisms that run automatically when you’re in physical danger.

When we feel safe, we’re in our comfort zones, where we perform well, set appropriate boundaries, rest, recharge, and reflect. It feels good when we’re in our comfort zones, but it’s not where we take risks or where much growth takes place. Development takes place when we’re on the far edge of our comfort zones, stretching existing skills and abilities. When a stretch is in reach, but we feel unsafe anyway, one of our innate survival mechanisms can switch into gear and shut us down. Then, a mechanism designed to protect us short-circuits our growth and gets in the way of reaching our goals. This tendency can be mitigated in several ways we’ll look at later, but for now, I’ll mention one: kindness. As far back as Charles Darwin, scientists, philosophers, artists, and poets have drawn a straight line between our warmhearted urge to respond to suffering with kindness and the likelihood that we’ll survive, even thrive. To borrow from the preface of Dacher Keltner’s excellent book, Born to Be Good: “[S]urvival of the kindest may be just as fitting a description of our origins as survival of the fittest.”

I was introduced to the poem “Kindness” from Naomi Shihab Nye’s first poetry collection when I heard it recited by Jon Kabat-Zinn, the founder of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). Kabat-Zinn and his teaching partner Saki Santorelli (at the time, executive director of the Center for Mindfulness at the University of Massachusetts medical school) were international rock stars in the secular mindfulness world, and I was primed to listen. It was early morning, midway through a weeklong MBSR retreat/training in the late 1990s at the Mount Madonna retreat center in Northern California. Light streamed through the floor-to-ceiling windows in the meditation hall to backlight Kabat-Zinn, who was sitting cross-legged on a meditation cushion, up on a dais. The golden early morning light gave him and the entire session an otherworldly quality. He recited the poem from memory to a room full of meditators sitting around him in a semicircle, most of whom were also sitting cross-legged on cushions. One of the images in the poem stood out then and has remained with me since:

You must wake up with sorrow.

You must speak to it till your voice

catches the thread of all sorrows

and you see the size of the cloth.

I’m struck by how often I’ve remembered this image of the enormity of sorrow in the world since I first heard it. The phrase has come back to me when someone I love has fallen ill or has died and when the loved ones of people close to me have struggled with illness or death. The size of the cloth hit me at an even greater level of magnitude as I watched news coverage of the Twin Towers coming down on 9/11 in New York City. The size of the cloth was almost unimaginable when I saw footage of the refrigerated trailers parked in front of hospitals in New York City functioning as temporary morgues during the early days of the pandemic. Maybe the theme of Shihab Nye’s poem that “it’s only kindness that makes sense anymore” resonated with me because it echoed rabbinic sage Hillel the Elder’s call to action: “If not now, when? If not me, who?”

Scientists have long suspected that kindness in response to other people’s pain is a survival mechanism that’s wired into our nervous systems. What’s often harder for people to remember is that kindness in response to our own sorrow is also a survival mechanism. For many of us, being kind to ourselves is more of a leap than being kind to others. It was for me. I thought kindness was the Golden Rule we teach young children—do unto others as you would have them do unto you. It didn’t occur to me to apply the Golden Rule to myself. I wanted to be a good mother, a good partner with Seth in providing for our family, and to make a difference in the world. I was one of the lucky ones and wanted to pay it forward. There was no room for me to take it easy. The harder I tried to do good and be good, the more of a toll it took on me. Still, it didn’t register that the pace at which I was working was unkind to my family and me. I had to burn myself out emotionally and physically a few times before I could internalize the commonsense truth that discomfort is one way our bodies ask us to listen. Just as it took me a while to develop a more nuanced stance toward safety, it took me time to adopt a more expansive idea of kindness that included being kind to myself. Now, I make space for rest—sometimes with a calming 성남출장마사지—as a way to truly care for my well-being.

The practices and activity-based takeaways in this guide are designed for you to integrate into daily life easily. Doing them shouldn’t be a heavy lift and tax you, but sometimes, mindfulness and meditation bring up big feelings that are painful to confront. Please be kind to yourself. Take a break if you feel overwhelmed or if discomfort becomes too much to manage easily. Time is your friend when it comes to inner discovery, and you have plenty of room to allow the process to unfold at its own pace. There’s no need to rush to get something or go someplace; you already have what you need to become enlightened.

WRAP-UP: Safety

Identifying your safety needs and factoring them into your choices are a meaningful and effective way to be kind to yourself. Ask yourself, “What do I need to feel safe?” “Are my safety needs being met?” “How?” If they aren’t being met, “Why not?” Remember that whether you feel safe depends on various factors, including if you’re tired, hungry, or stressed. When safety and inclusion needs are unacknowledged and unmet, our nervous systems are ripe to become hijacked by one of our innate survival mechanisms.

Reflecting on safety needs can seem like a waste of time. When you’re in your comfort zone, it’s easy to miss the point of looking at what it takes to feel safe. Here’s why you should do it anyway: If you identify your safety needs up front, while you’re in your comfort zone, you can better take care of yourself later when you are outside of it. (We’ll dig deeper into safety and inclusion needs in the context of interpersonal relationships later.)

Practice

Find a comfortable place where you won’t be interrupted. Close your eyes or softly gaze ahead or downward. A few breaths later, listen for the loudest sound. When you are ready, listen for the quietest sound. Don’t chase a sound that’s hard to hear; relax and let it come to you. Let your mind be open and rest in the whole soundscape. Ask yourself, “What does it take to feel safe and welcome in a new situation?” Hold the question in mind and listen to the answers that emerge. When you’re ready, open your eyes if they are closed and jot down your insights. Then, draw three concentric circles on a blank piece of paper. Prioritize your insights by writing the most important ones in the inner circle. Write those that are the least important in the outer circle. Write what’s left on your list in the circle in between. All your insights matter, but double-check to ensure the essential items are in the inner circle. Review the diagram and consider ways to increase the odds that, in a new situation, you will feel safe and included. Save the diagram and put it aside. This is the first of four concentric circle drawings I’ll ask you to make in this guide. We’ll revisit them in the second to the last chapter, “What Matters Most.”

Takeaway

How might connecting with playfulness, attention, balance, and compassion help you feel safer and more welcome?

WRAP-UP: Kindness

Throughout our evolutionary history, humans have relied on kindness to survive. Strong social bonds, effective communication, and meaningful collaboration create a supportive external environment that allows us to thrive in diverse situations and overcome challenges. Similarly, we create a supportive internal environment when we are kind to ourselves, one where we become more emotionally resilient. Kindness is a self-reinforcing behavior. By being kind to ourselves, we can better support and care for those around us. By being kind to others, we build trust, strengthen relationships, and create a sense of social support and belonging that helps us cope with stress and navigate adversity.

I first learned about the following self-compassion practice reading Zen priest Edward Espe Brown’s book No Recipe: Cooking as a Spiritual Practice where he writes: “[I]n the early ’80s, when Thich Nhat Hanh was giving a talk prior to departing from the San Francisco Zen Center where I was living, he said he had a goodbye present for us. We could, he said, open and use it anytime, and if we did not find it useful, we could simply set it aside. Then he proceeded to explain that, ‘As you inhale, let your heart fill with compassion, and as you exhale, pour the compassion over your head.’”

Practice

Imagine you are in a sweltering but beautiful jungle, holding a coconut shell in one hand. Can you feel the rough shell against the palm of your hand? Picture a wooden barrel filled with cool rainwater on the ground next to you. Can you see your reflection in the sparkling water? Imagine the rainwater is a nectar of compassion that soothes busy minds and big feelings. As you breathe in, imagine filling the coconut shell with compassionate rainwater. As you breathe out, imagine pouring the nectar of compassion over the crown of your head. Let go of the images of the bucket and coconut shell to focus on sensation. Imagine what it would feel like for a nectar of compassion to wash over you and soothe your body from head to toe. Starting at the crown of your head, feel the compassion rinse slowly over your face and head, then over your neck, shoulders, chest, upper arms, lower arms, and hands. Move your attention to your torso and imagine feeling a nectar of compassion wash slowly over your torso, pelvis, upper legs, knees, lower legs, and feet. When you’re ready, lightly rest your attention on your outbreath. If thoughts and emotions arise, don’t fight them. With no goal or purpose, allow your mind to be open and rest.

Takeaway

Find at least one way to be kind to yourself today, then see if there’s a ripple effect.

NOTES

- Dacher Keltner, Born to Be Good: The Science of a Meaningful Life (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009).

- Naomi Shihab Nye, Words Under the Words: Selected Poems (Portland, OR: Eighth Mountain Press, 1995).

- The source of the well-known and often misattributed maxim is described in “If Not Now, When? A Recent History of Hillel’s Misattributed Maxim from Ivanka Trump to Ronald Reagan,” Tablet Magazine, September 12, 2016, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/if-not-now-when-a-recent-history-of-hillelsmisattributed-maxim-from-ivanka-trump-to-ronald-reagan.

- Edward Espe Brown, No Recipe: Cooking as a Spiritual Practice (Louisville, CO: Sounds True, 2018).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

SUSAN KAISER GREENLANDis a mindfulness educator and bestselling author, specializing in distilling global wisdom traditions and scientific research into straightforward everyday practices. In the early 2000s, she helped pioneer the introduction of secular mindfulness into classrooms through her Inner Kids model. After decades of working with children and adults and writing two widely translated books, Susan’s latest work has culminated in a new book called Real-World Enlightenment. Her work has been featured in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, USA Today, and CNN. To learn more, please visit www.susankaisergreenland.com.

Seeing and Not Seeing

© 2024 Judith R. Smith, PhD, LCSW

Is love blind? Romantic love and maternal love can be exhilarating, but the scientific truth is that loving feelings can get in the way of seeing things clearly. Andreas Bartels, a neuroscientist in Tübingen, Germany has shown that maternal love—with young children—can, in fact, be blind. He has pinpointed how a mother’s connection to her young child deactivates the part of her brain that is responsible for negative emotions and critical assessment. In other words, a mother’s positive feelings that arise from her developing attachment to her child overrides the part of her brain that is responsible for more objective appraisals. Being hopeful and optimistic regarding your child’s future is a good thing. But wearing rose-colored glasses with your adult child can be dangerous over the long run. These filters, which mental health professionals call denial or minimalization, can block a parent’s ability to make realistic assessments of their adult children’s needs, as well as their own.

I discovered the critical importance of “seeing” or acknowledging the reality of an adult child’s problems when I conducted one of the few empirical research projects on mothering in later life. Very little is known about the stress that older women/mothers experience when their adult children’s lives are detoured by mental health or substance use challenges. Much more is known about the stress on adult children when their parents become frail, than is known about the impact on the emotional life of older mothers when their adult children are unable to “launch” or maintain their self-sufficiency. In this essay, I describe how the pathway to getting help for a troubled adult child (and for the mother, herself) can be impacted by the parents’ ability or inability to acknowledge the depth of their sons’ or daughters’ problems.

I interviewed 50 older mothers, all of whom self-identified as having an adult child whose problems were worrisome to them. There were many distinctions between these mothers. Some were widowed. Some were married. Some were rich, while others were poor. They came from different races and ethnic backgrounds. The type and severity of the children’s problems varied greatly, too. Some were providing housing for their dependent adult children, some were not. Yet, among these distinctions, they shared a view of mothering that had led them to become their child’s safety net, despite their advanced ages and their sons’ and daughters’ status as “adults.” Each explained their situation with this simple sentence: “I’m her (his) mother.” Yet, each of them reported difficulty in acknowledging the level of their adult children’s problems.

Closing My Eyes

Lucy, a dynamic 69-year-old woman, described how she discovered her blind spots. She laughed, telling me how frightened she got when she saw that her son Carlos had put a towel in front of his door. She shared with me what she was thinking when she saw the towel. His marriage had recently ended in divorce, he was separated from his children by three thousand miles…maybe he was depressed and trying to kill himself?

Lucy called her daughter for help. She didn’t know what to do about her son’s possible depression. “Ma, he's smoking pot in that room and that's why the towel is there—so you can't smell it.” Lucy smiled as she described how, at her daughter’s suggestion, she went into Carlos’ room and found little pieces of a joint on the window, as well as a spray can that he was using to cover the odor. “I couldn’t believe how long I had been blind to what was happening. I had smelled something sweet, but I had told myself ‘That’s nice—it must be incense.’”

After this revelation Lucy started to pay more attention to what her son was doing. Money had gone missing from her drawer. “You know, I'd have maybe $180 dollars, I'd look and there'd be $140. I had been questioning myself, ‘Where could I have spent that missing $40?’” Nevertheless, she kept asking Carlos to go to her bank for her so that she didn’t have to walk up and down the five flights in their apartment building. “I’d tell myself I can trust him. He always gave me the receipt that showed the $200 that I asked him to get.”

After realizing that he had been covering up the fact that he was smoking pot in her house and purposely trying to deceive her, she saw that on the very same day that there was a withdrawal for $200, there would also be another transaction for $40. Her first reaction was to assume that the bank had made an error. She called them to report the problem. “For some reason, I didn't want to believe what was going on.” She paused for a long minute and described how hard it was for her to really believe that her son would steal from her. She assumed that he respected her and appreciated all she had done for him, raising him as a divorced, single, working mother. She had done everything she could to make him a good man.

Many mothers are like Lucy and have a hard time admitting that their adult children are stealing from them. They’re reluctant to admit what the evidence is telling them.

I coined the name “difficult adult child” to describe the situation I learned about when interviewing older mothers who were being affected by their adult children’s problems – including serious mental illness and/or substance use disorder. I chose this name to acknowledge not just the challenges faced by the grown children, but the hardships passed along to the mothers who cared for them. If “difficult” seems a harsh label—one that blames, not just identifies—consider how the dictionary defines difficult: 1. when something is hard to do or carry out; 2. hard to deal with, manage or overcome, and 3. hard to understand. Mothering adult children is hard to do. Tolerating the tensions in a relationship with a struggling adult child is extremely hard to manage. And understanding the problems that might have caused your child’s situation are hard, and knowing how to intervene can feel impossible. Naming an adult child “difficult” is not meant to be pejorative.

There are no models for transforming mothering in later life with difficult grown children, but there is value in adapting the Stages of Change Model which has demonstrable results in helping people change many kinds of behaviors. Also known as the TransTheoretical Model, TTM was introduced in the late 1970s by researchers James Prochaska and Carlo DiClemente, two psychologists who were studying ways to help people quit smoking. The first stage of change in this model is acknowledging that there is a problem. The authors name this moving from pre-contemplation to contemplation. Parents in pre-contemplation do not allow themselves to see that there is a real problem in their adult children’s behaviors.

Only Seeing the Good

Loretta’s story illustrates how it can take fifteen years for a mother to move from precontemplation to contemplation to action. Loretta was 82 years old. Tall and thin, she spoke with a musical lilt in her voice, still maintaining her Jamaican accent. She was physically mobile and relatively cognitively sharp, although it was hard for me to follow the timeline of the stories about all the years of legal battles she had had with her son, Jason. When we met, it had been three years since she had had contact with him or her grandchildren. She had no idea where or how they were living. Last she knew, they were homeless.

Years ago, Loretta and her husband Karl had been able to purchase a small home in Brooklyn, where she still lived. Karl had died when Jason was just ten years old. Loretta had been a widow for many years when Jason, aged thirty, asked if he, his girlfriend Zahra, and their one-year-old daughter could stay with her temporarily. She remembers thinking, “He’s not a bad kid. Why not?” I was left speechless when she described the way that he and his wife had behaved towards her during the many years that they lived with her. Her daughter-in-law treated Loretta with disrespect, made no effort to clean the kitchen that they shared, and Loretta’s son seemed to instruct his kids to lie to child protective services, accusing Loretta of having hurt them. Jason wanted to have Loretta evicted from her own home. Apparently, he believed that his father wanted him to have the house and that was why, according to Zahra, he felt justified in his attempts to use the law to challenge his mother’s ownership of her home. As I listened, I kept trying to understand the timeframe. When had the problems begun? How had she allowed this to go on for so long? What had kept her from protecting herself earlier on from her son’s continual aggressive behavior and disregard for her comfort?

Loretta told me stories about Jason as a young boy. She proudly recounted that at age 11, when he was in 6th grade, he refused to follow the Board of Education’s decision that he enter Special Education classes because of his behavior problems. He wrote a letter to the Chancellor of Education stating his case for why he believed he should be able to attend regular classes. His request was granted. Back then, Loretta and Jason’s siblings admired his fighting spirit and perseverance. They believed this meant that he would go far in life. Loretta’s maternal optimism was also evident when she also told me what a great athlete Jason had been, how he had gotten a basketball scholarship to college, and about her and Jason’s firm belief that he still might be recruited for a national team in South America, even though it had been ten years since he had left college where he played ball.

Side by side with describing his talents, Loretta suggested that Jason had a way of fudging the truth. He claimed that he had graduated from a private four-year college, something Loretta knew not to be true. He would always present his leaving a job as his choice—not that he was let go. As Loretta described Jason’s actions prior to her having him evicted, I heard her describe the same personal characteristics—pushy, perseverant, and determined—that she had valued in him at age eleven. Yet, now in his forties, living with his mother, his goal was not to avoid Special Education classes, but to gain ownership of his mother’s house which he believed he was entitled to.

Loretta finally got help from a Legal Center for Seniors. They offered her free legal help to respond to Jason’s constant use of the courts in his efforts to take her home away from her. It wasn’t simple to have him evicted. He was very savvy and had taught himself how to use the law to harass his mother. One judge got so annoyed at his endless trumped-up charges that he forbid Jason from ever coming into his court again. After what seemed like years of attempts to stop his abuse and legal attacks, Loretta secured an exclusionary order of protection forbidding Jason or his family to enter her home. But Jason was not to be stopped. He managed to go to another court, find a second judge, who issued a warrant for Loretta’s arrest unless she allowed him entry.

When the police arrived, Loretta did what the public attorney had instructed her to do. She told the police officers that she had obtained an exclusionary order of protection against her son and would not allow him back into the house. Instead of understanding the situation, the police arrested Loretta and took her away in handcuffs. She sobbed as she described to me what it was like for her to be in jail for two nights. The cell smelled of urine, there was no working toilet, and no one gave her anything to drink for hours on end. Telling me, three years later, about this experience, she reexperienced the humiliation and cried. However, it was the sting of her son having her arrested that became a turning point for Loretta. Sitting in the jail cell, she fully acknowledged that there was something wrong with him, “if he could be ok with his mother being put in jail.”

Loretta had been using what mental health professionals call the defense mechanism of “minimization” or filtering out the negatives in a situation and only letting herself focus on the positives. This generosity of spirit, or seeing only one side of a situation, was likely at play when she accepted her son’s request that he move into her small one-family home with his new baby and girlfriend. When she told herself “he’s a good kid,” she was discounting what she also knew about his difficulty with authority and his inability to get along with people, as well as his history of lying or distorting the truth for his own ends. Loretta’s capacity to tune out the problematic effects of Jason’s behavior can explain how she had allowed him and his expanding family (he had six children when they were finally evicted) to continue to live with her, all those years. Her wish that things would eventually go well for Jason took priority over acknowledging her own discomfort.

Not Wanting to See

Rosanne described herself as someone who could never talk about or address upsetting things. She had stayed in a very unhappy marriage for years. When her son, Derek, cut off all contact with her several years back, she never discussed the situation even with her daughter, who she saw every week. She lived her life squashing down all discomfort. Soon before she had chosen to be interviewed by me, Rosanne learned that Derek might be in serious trouble. Derek was living on his own, unemployed, and supported by a monthly allowance from a family trust that was administered by a lawyer and did not require his parents’ involvement. Derek had maintained some contact with his father, Michael, from whom Rosanne was divorced. It was Michael who told Rosanne that he had gotten a troubling call from Derek demanding that he give him $5,000 immediately. Michael and Rosanne feared that Derek might be involved in drugs or gambling debts and that explained why he needed the money. Perhaps someone was after him. Rosanne was scared. She considered hiring a detective to find out how serious the situation was. She was afraid for her son’s safety.

To have hired a detective sounded to me like a metaphor for changing her lifelong mode of not allowing herself to acknowledge the things that upset her. If she had followed this idea and had hired a detective to investigate what was happening with Derek, she would have been trying out a new way of being. Instead, she decided against getting involved. She told her ex-husband to give their son the money with no questions asked. Her rationale was that she did not feel strong enough or savvy enough to know what to do if she were to learn that her son was in serious trouble with mobsters or drug dealers. She did not believe that she had the capacity to help.

Seeing and Intervening

In contrast, Wendy allowed herself to act on her worries about her daughter’s safety despite her advanced age (66) and belief that her mothering tasks were done. But when her 40-year-old daughter Mindy started making changes in her life that seemed out of character, Wendy—with time—allowed herself to acknowledge her concerns.

The first surprise came when her daughter announced “out of the blue” that she was leaving her engineering job to become a yoga instructor. She explained her job change as part of a larger evolution into a more spiritual existence, and that she was also changing her name, legally, to Vishnu. The name change really bothered Wendy and she even refused a birthday present Mindy had sent because it was signed from “Vishnu.” Several months later, Mindy reported that she was getting a divorce from her husband. Wendy and her husband, Robert, were very surprised, and asked many questions to be sure that Mindy was making the right decision, but accepted that she knew what was best. They had always had full confidence in their daughter’s choices up until then. They figured that Mindy was going through a spiritual crisis which would lead to something new for her. Yet, as they noticed more and more odd changes in their daughter, they started to make more frequent calls and visits with Mindy in the hopes of monitoring more closely the changes that seemed confusing and surprising.

With time, their dis-ease with Mindy’s erratic behavior motivated them to seek out information about symptoms of mental illness and possible treatment options. Neither of them had ever had any contact with the mental health system. First, they relied on the internet for information, then they went to local doctors and started to network with everyone they knew to understand their daughter’s situation. They were able to face the situation, as well as their lack of knowledge. They got educated quickly enough so that they could intervene and protect their daughter when that became a necessity.

Seeing Leads to Action

Seeing an adult child’s difficulties, acknowledging the impact of their behavior on themselves, or on you, is the first step in a mother’s change process. There are two kinds of changes that mothers may make. One is to more clearly see how an adult child’s life may need a parent’s intervention, even though this will require getting involved as a helper when you believed that active parenting was already over. The second kind of change is related to removing or changing an adult child’s ability to hurt you, as in the case of Loretta. Loretta’s filtering out of the ways in which she felt pushed around and taken advantage of by her son were her way of holding on to her image of her son as a “good boy.” Wendy and Robert took a while to see that their daughter’s surprising and erratic behavior was, in fact, mental illness. But once they saw that she was in trouble, they acted and did something that was hard: committing their daughter against her will to a psychiatric hospital. But this saved her life. Seeing is the first step in the change model for dealing with a difficult adult child.

Practice: Taking off your Rose-Colored Glasses

Sit in a quiet place and imagine having an honest discussion with yourself. Explore examples of your adult child’s recent behavior that are making you feel uneasy. Push yourself to imagine the consequences if you allow yourself to fully face your currently buried worries about this behavior. Are you afraid that you will not know how to help if you acknowledge their vulnerable situation? Will you feel like a bad mother if you acknowledge how your adult child is suffering? Who are you protecting – yourself as the mother or your adult child?

Difficult Mothering is Challenging

Most of us became parents believing that when we are in our 60’s, 70’s or 80’s, our active parenting will be behind us. But when you have an adult child who is suffering with serious mental illness and/or substance use disorder, your support is often needed, once again. Despite being tired and wanting to avoid conflict in later life, your adult children who are vulnerable will benefit if you let yourself see their difficulties. Seeing may make you initially uncomfortable, because knowing that they are in trouble may push you to want to find an appropriate way to respond and you may feel unprepared. There are many sources of help for older parents. Learning how other parents are coping with this family situation is an excellent resource. National Association of Mental Illness (NAMI) and Al-anon both offer groups for parents with adult children with mental health (NAMI) or substance use (Al-anon) issues. You can also call your State Area Agency on Aging (AAA) and they will suggest who you might contact in your area. Finally, if you acknowledge that you or your adult child is in a very dangerous situation, call 988 - the nationwide three-digit number for anyone to be connected to the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, or visit 988Lifeline.org.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

JUDITH SMITH, PHD, LCSW is a senior clinical social worker, psychotherapist, professor,and author of Difficult: Mothering Challenging Adult Children through Conflict and Change, Rowman & Littlefield, 2022. She lives in NYC. Her research has been published in many professional journals. She facilitates support groups for older mothers with adult children who have serious mental illness, substance use disorder, and/or chronic unemployment. https://www.difficultmothering.com/.

The Healing Power of Acceptance

© 2024 Jamie Lynn Tatera

The comics and activities in this article are excerpted from the Mindfulness and Self-Compassion Workbook for Kids, Volume 1 , by Jamie Lynn Tatera; Foreword by Kristin Neff (Wholly Mindful, October 2024). Reprinted with permission.

Imagine the following: There is a lot of traffic, and you arrive late for an appointment; Your flight has been delayed, and you miss your connecting flight; You (or your kids) get sick…again! These are all circumstances that call for moment-to-moment acceptance. And then there are more challenging conditions that call for ongoing acceptance: political unrest, chronic health problems, and financial systems beyond our control.

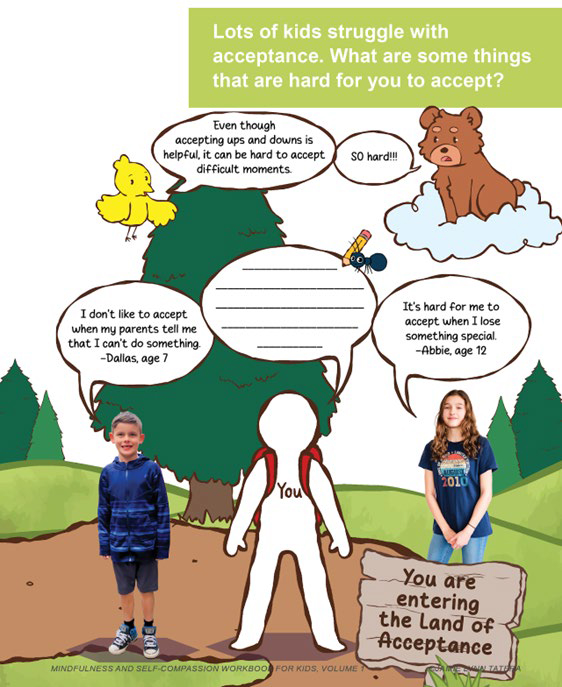

Acceptance can be one of the hardest things to cultivate. It can be hard for adults to face difficult situations and feelings, and it’s especially hard for kids. As a kid, there are so many things you cannot control, and adults make a lot of your decisions. And just how can we accept things that we don’t approve of?

In the context of mindfulness, acceptance does not mean that we agree with or condone what is happening. Rather, acceptance involves nonjudgmentally acknowledging that an experience is occurring. When we are able to understand and tolerate that things don’t always go as we wish, we are more able to respond adaptively moving forward.

Even though meeting reality with mindful acceptance is helpful, it is not always easy. Resistance is a natural response to encountering situations that we dislike. Even an amoeba moves away from a toxin in a petri dish! But too much resistance causes unnecessary suffering. As a mindfulness and self-compassion teacher for adults and youth, it is my job to help kids, teens, and adults learn to meet challenging circumstances with a balance of awareness, acceptance, and empowered action.

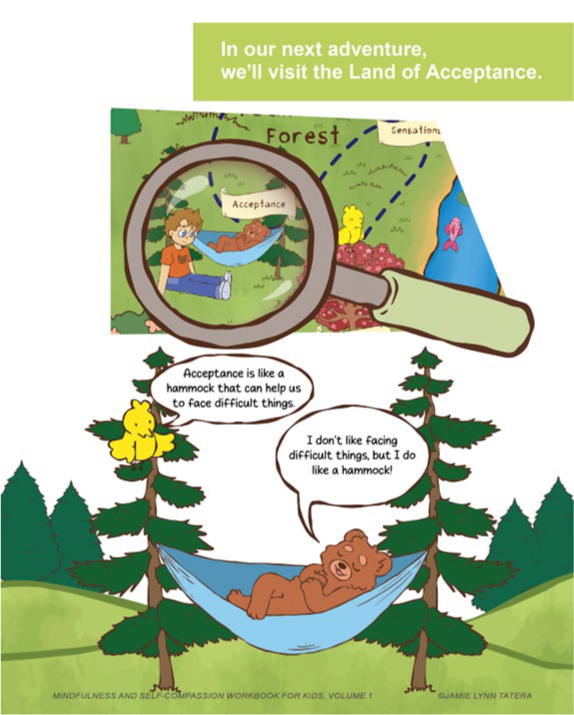

This article includes excerpts from the Mindfulness and Self-Compassion Workbook for Kids, Volume 1. The workbook invites kids to go on a quest, and Acceptance is one of 16 lands that children travel through. Please tap into your inner child and enjoy some lessons that can help you move into the hammock of acceptance.

Humor is a great friend to bring along on the journey of acceptance. Life can be hard, and laughter can make difficulties easier to bear (pun intended!). In my work with kids, I juxtapose humor with life lessons.

Common Humanity

A tenet of many spiritual traditions is an understanding that suffering is universal, but the phrase, “suffering is a part of life” can be challenging for some adults and kids. More accessible phrases that convey a similar idea include:

Ups and downs are a part of life.

Imperfection is a part of life.

Remembering that everyone has ups and downs can help us feel more connected during challenging moments. We can be mindful of our resistance to difficult feelings, and we can remind ourselves that it is human to feel as we feel. Even the struggle with acceptance itself is one that we all share. Remembering that we are not alone can give us a sense of “common humanity” when things go wrong, which is an important element of self-compassion.

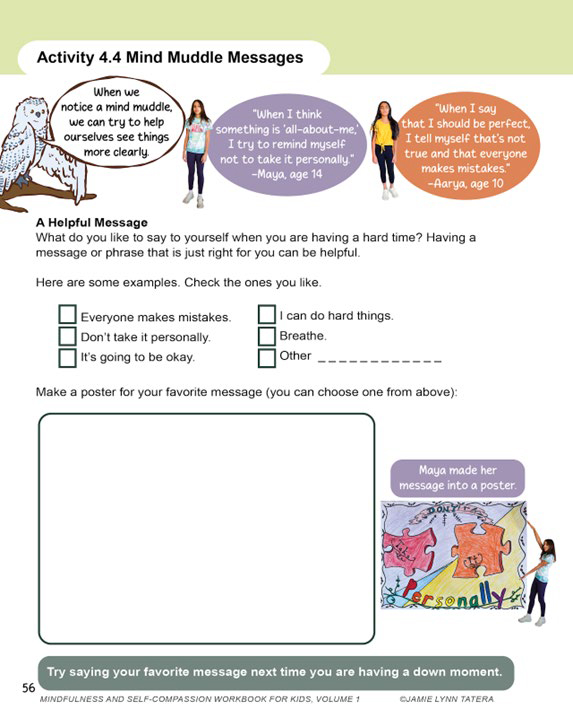

Thought Distortions

The way we think about our difficult moments can make a big difference in how we feel. Cognitive distortions like black-and-white thinking and should-or-shouldn't thinking can make a difficult situation even more challenging. In my work with kids, I refer to cognitive distortions as “mind muddles.” The below pages highlight some common mind muddles that can compound struggles and make it harder to accept the present moment.

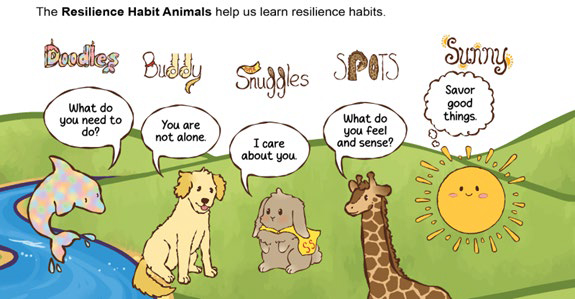

Resilience Habits

Sometimes our mind is so riddled with resistance and difficult thoughts that acceptance feels out of reach. Elements of self-compassion (and resilience habit animals) can help us come back to center:

Mindfulness (aka “Spots”)

Mindfulness meets us just where we are. If we are in a state of non-acceptance, we can be mindful of that, too. We can be mindful of all our thoughts and feelings as well as our five senses.

Common humanity (aka “Buddy”)

Whatever we are experiencing is human. We belong to humanity.

Self-Kindness (aka “Snuggles”)

We can soothe ourselves with words of acceptance and care, and we can motivate ourselves with supportive messages.

Kind Actions (aka “Doodles”)

Sometimes the choice is not whether or not we will hurt, but rather what we will do while we are hurting. We might call a friend, go for a walk, have a cup of tea, read a book, or attempt to solve a problem. Taking action in the presence of struggle is a powerful form of kindness.

Notice the Good (aka “Sunny”)

The sun is still present even when it’s hiding behind a cloud. When the time is right, we can help ourselves to notice and appreciate what is good. Remember that goodness and struggle can coexist side by side.

Self-compassion includes both tender acceptance of ourselves and our feelings as well as strong actions to try to alleviate suffering. The tender and strong sides of self-compassion are complementary. We can create change most effectively when we first bring mindful awareness to the moment and acknowledge that in this moment, things are exactly as they are. Mindfulness and self-compassion can help us move through resistance and struggle into the land of acceptance.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

JAMIE LYNN TATERA is a certified educator, author, and curriculum designer with a passion for helping children and their caregivers become more selfcompassionate. She is the creator of the Mindfulness and Self-Compassion for Children and Caregivers (MSC-CC) program, a parent-child adaptation of the research-based Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC) training by Drs. Kristin Neff and Christopher Germer. Jamie Lynn trains educators, families and clinicians in her resiliency programs, and she has a wealth of experience teaching mindfulness and self-compassion to adults, children, teens, and families. The pages from this article are excerpted from her new book, Mindfulness and Self-Compassion Workbook for Kids, Volume 1. Visit https://jamielynntatera.com to learn more.